Every contact leaves a trace and everything we touch leaves a fingerprint. And despite what TV and movies often depict, a fingerprint can be detected even after it has been wiped off.

It’s common to see someone in a movie or TV show wipe their fingerprints from a surface or a weapon to avoid being caught by investigators. It’s so common a trope that one might think that cleaning your fingerprints is actually a foolproof way to avoid being caught.

But how true is that? In other words, can you really escape detection if you just clean your fingerprints from a surface after committing a crime?

Before we answer the question, let’s talk about fingerprints in general.

Recommended Video for you:

What Is A Fingerprint?

Our fingerprints have been with us since before we were born and will stay with us throughout our lifetime. Those grooves and ridges on our fingertips not only improve our touch perception and ability to grip things, but also provide us with a distinctive identification mark.

Every person on this planet has a unique set of fingerprints. Not even identical twins who have the same DNA code share the same fingerprints!

This peculiar property of friction ridge impression, aka fingerprints, has been a part of crime-solving for over 100 years, but its use as a personal identifier or even a legally binding signature has been around even longer.

What Makes Fingerprints So Unique?

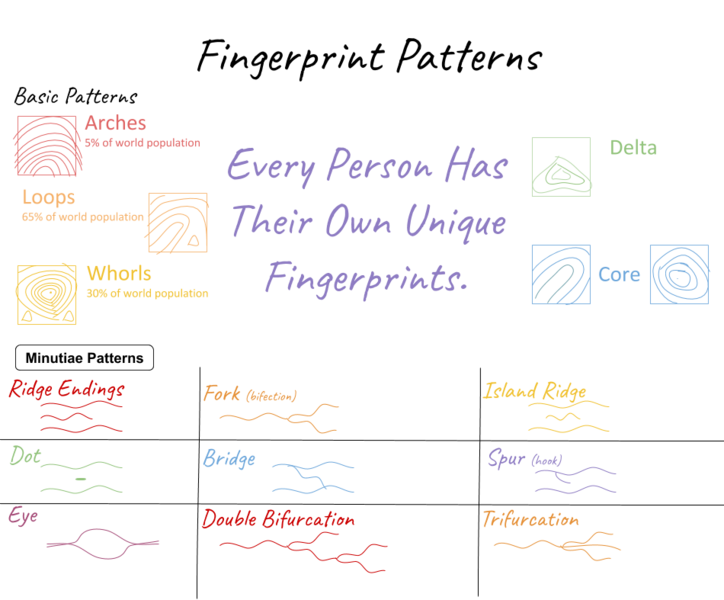

The folds on our skin give rise to ridges on our fingertips that create a unique arrangement of loops, whorls, and arches. These three shapes further give rise to an even more intricate and distinguishing pattern, known as the minutiae, which consist of lakes/enclosures, bifurcations, trifurcations, ridge endings, and many other defining ridge characteristics.

There are billions of people on this planet and everyone has their own tapestry of loops, whorls, ridges, and minutiae. The presence of a searchable and distinct sequence of shapes can act as anchor points for forensic experts and the fingerprint recognition software when cross-referencing found prints with biometric databases.

But how does one leave this unique print on objects if their hands aren’t soaked in ink?

How Do We End Up Leaving Fingerprints On Things We Touch?

The keyboard keys you just touched or the container you are drinking water from hold the invisible evidence of your presence; they now carry a trace of you because every contact leaves a trace.

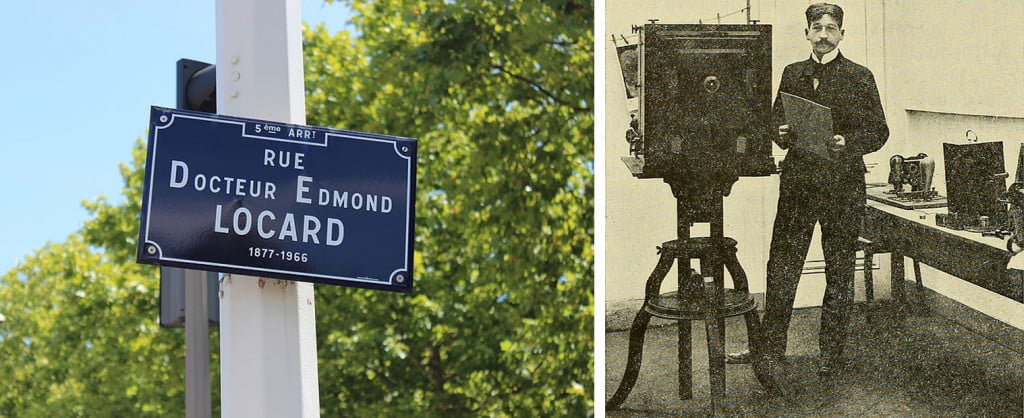

This phrase is known as the “Exchange Principle” and forms one of the basic principles of forensic science. It was popularized by Edmund Locard, one of the pioneers in the field of forensics, who showed that every time two objects came in contact with each other, there was an exchange of material between them.

Even if your fingertips aren’t soiled by blood, dirt, or Cheeto dust, they still leave behind chemical imprints on the things you touch because the sebaceous glands under our skin secrete a cocktail of sweat, oils, and amino acids. These natural secretion traces help crime scene investigators (or CSIs) lift even the invisible fingerprints from a crime scene.

How Are Fingerprints Lifted From A Crime Scene?

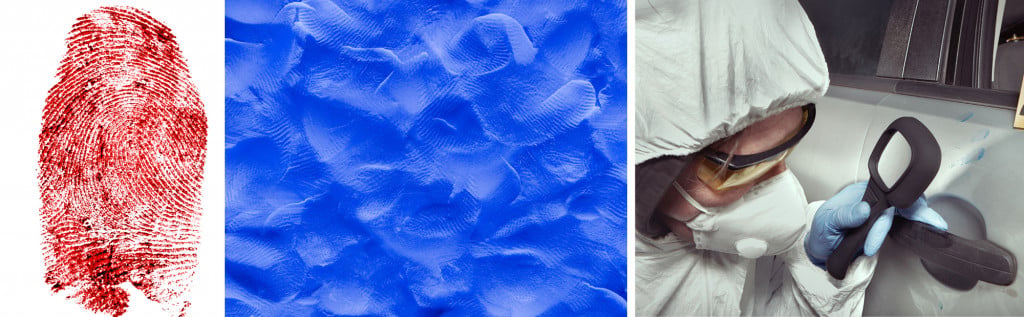

CSIs look for three different types of fingerprints: Patent, Plastic and Latent.

Patent Fingerprints are visible to the naked eye, for instance, a finger soaked in blood.

Plastic Fingerprints are left on soft surfaces, like soft wax or wet paint.

Latent Fingerprints are the invisible impressions created by skin secretions on various surfaces.

The CSIs usually begin by photographing the patent or visible fingerprints under normal light, if they’re clear enough, or they can use alternative light sources, such as UV black lights, to enhance the prints. Then they look for plastic fingerprints left on soft surfaces that can be lifted off by pouring a liquid, such as plaster, molten alloys or silicon rubber, which can later harden and create an impression of the print.

And now for the most challenging part, the hunt for lifting latent fingerprints. Since they are invisible or barely visible, CSIs use chemistry to enhance such prints, if any are present.

The most common technique and the one many of us might have already seen on TV shows is the use of fingerprinting powder. CSIs use their trusty brush and a palate of fingerprint powders to visualize prints from smooth and textured surfaces. The fingerprint-dusting powders stick to oils and moisture left by the ridges on our fingertips to create a visible print that is then lifted off using transparent tape.

The powders used vary from surface to surface. For example, aluminum powders are preferred for glass surfaces, while brass or granulated jet black is used on silvery surfaces to create better contrast. Fluorescent powders are also used to enhance prints on multicolored surfaces.

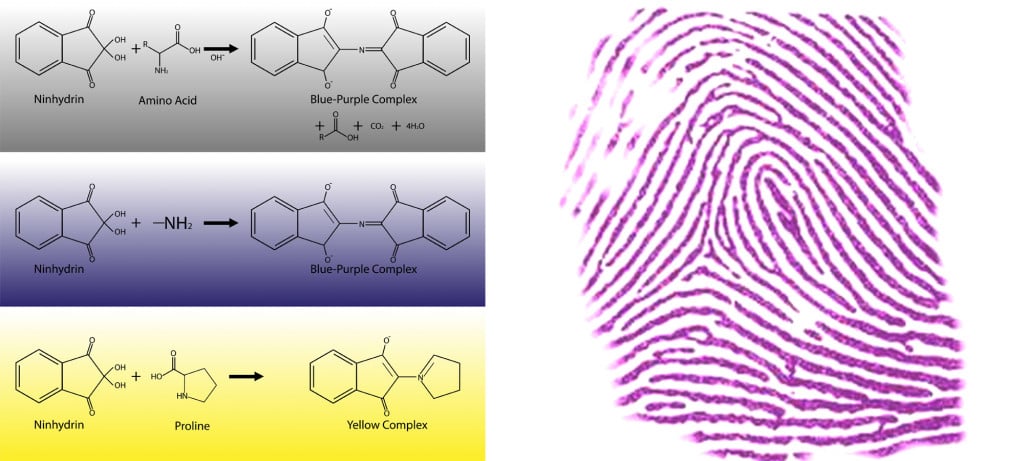

For porous surfaces like paper or walls, fingerprints are detected by spraying a solution called ninhydrin on the surface where a print can be found. This ninhydrin solution reacts with the amino acids present in sweat and turns purple due to the formation of Ruhemman’s purple.

In some cases, CSIs will use cyanoacrylate or super glue fumes to enhance a latent fingerprint from a rough surface. The cyanoacrylate molecules react with skin residue and polymerize to create a 3D matrix of the fingerprint. If that doesn’t work, they might try the most recent and advanced method—vacuum metal deposition or VMD.

This method deposits a thin layer of gold and zinc. A part of the gold layer diffuses with the skin oils and the rest remains free. When the zinc is coated, it attaches itself to the undiffused free gold, creating a negative contrast of the fingerprint. Though quite expensive, this is the fastest method for developing a fingerprint on extremely tricky surfaces like wood or fabrics.

The investigators exposed the curtains near the entrance of the store to VMD in hopes that the burglar might have touched them while running out. Unfortunately, this led to a dead end because they found multiple fingerprints and there was no way of determining which were the burglar’s and which came from the employees or other customers.

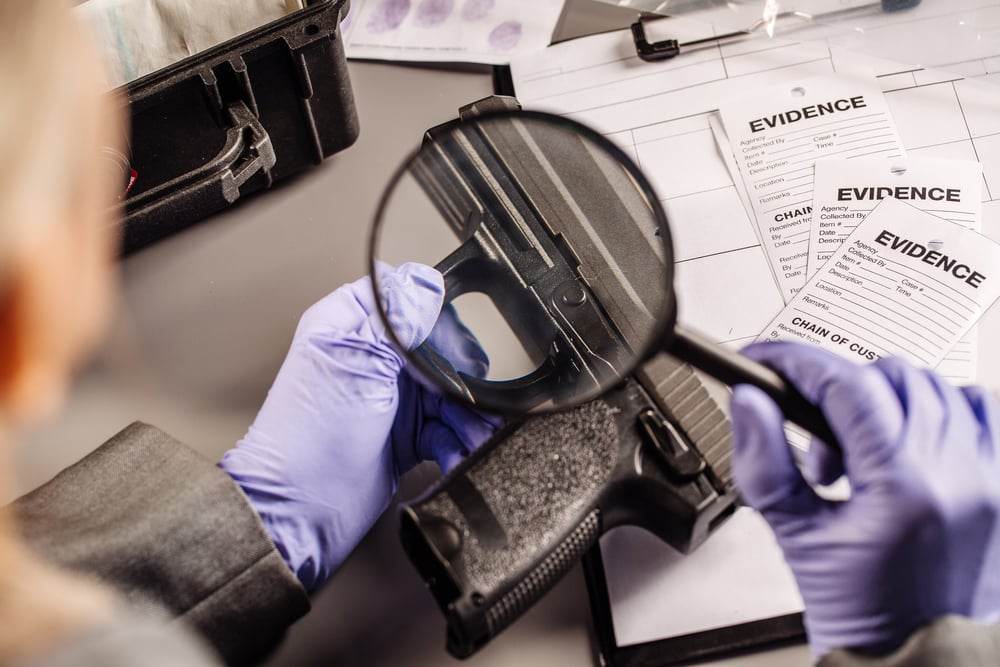

The only thing solely handled by the criminal was the gun. Even though a preliminary test didn’t reveal any fingerprints, the cops were still hoping they could recover prints from the gun once it was sent to a more advanced forensic lab.

Can Fingerprints Be Lifted From A Gun After It Has Been Wiped Off?

The answer is… yes!

Scientists have developed a method that can visualize prints from even the faintest fingerprint deposits left after the metal is wiped off. This technique uses a colored electro-active film that uses fingerprint residue as a stencil for blocking the electric current. Once a voltage is passed, the oily regions deflect the colored substances surrounding bare regions, which gives rise to a negative ridge pattern, similar to VMD.

Now, coming to our second piece of evidence—the bullet casing. Scientists can now identify who handled a bullet before it was fired by visualizing corrosion on the brass casing. The oil or sweat marks left by finger ridges can cause the brass casing to corrode, which is further accelerated by the heat produced while firing the bullet. Thus, scientists coat the casing with a conducting powder and pass an electric current.

The powder moves and sticks to the corroded spots—and voila! We have a fingerprint.

Many such phenomenal advances are happening in forensic technology, so the days of wiping down weapons to remove fingerprints will soon be from a bygone era. Say goodbye to the idea of wiping off fingerprints to protect your innocence!

References (click to expand)

- Elkins, K. M. (2018). Introduction to Forensic Chemistry. CRC Press

- Crime Scene Chemistry – Fingerprint Detection. Compound Interest

- Mcdermid V. (2014). Forensics: The Anatomy of Crime. Profile Books

- White P. (2010). Crime Scene to Court: The Essentials of Forensic Science. Royal Society of Chemistry

- Sapstead (nee Brown), R. M., Ryder, K. S., Fullarton, C., Skoda, M., Dalgliesh, R. M., Watkins, E. B., … Hillman, A. R. (2013). Nanoscale control of interfacial processes for latent fingerprint enhancement. Faraday Discussions. Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC).

- Bond, J. W. (2008, July). Visualization of Latent Fingerprint Corrosion of Metallic Surfaces. Journal of Forensic Sciences. Wiley.