Table of Contents (click to expand)

To keep cool in hot weather, our ancient ancestors relied on architectural elements that made clever use of fluid mechanics and thermodynamics.

Imagine coming home on a sweltering afternoon, only to find the AC remote missing, or even worse, the AC not working at all! As the resident of a tropical country, when faced with this sort of adversity, there was very little sympathy from the parents:

“As kids, we had no air conditioning.”

Air conditioners, as we know them, have been around for only a hundred years or so, but how did the ancients keep cool?

Recommended Video for you:

Importance Of Temperature Regulation

Maintaining optimal ambient temperatures isn’t merely a luxury, it is critical to survival. Today, we are equipped with infrastructure, devices and even clothes that keep us protected from nature’s vagaries, not to mention the imminent threats of global warming.

Obviously, there was a time when electricity had not been harnessed to power devices, yet civilization thrived, giving us some of the most enduring elements of society, like architecture and culture. It is in these same places that we also find simple, yet profound lessons in thermodynamics, fluid mechanics, and HVAC.

This article will discuss how our ancients used science to keep themselves cool, not just in majestic palaces, but in common houses too!

How Did Our Ancestors Keep Cool In Hot Climates?

In the old days, HVAC systems were built into architecture, with very little dependency on equipment. Let’s look at some of these features and the science behind each one of them.

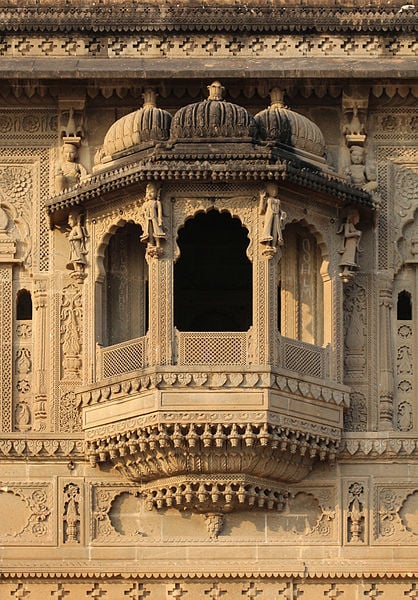

Jaali

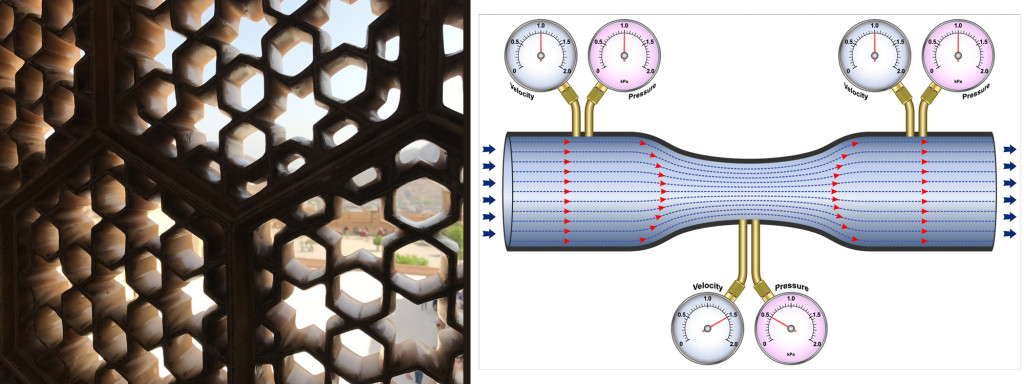

The Indian word Jaali, roughly translating to ‘net’, refers to a perforated framework of stone or wood, set into window openings. Its intricate design presents aesthetic appeal, while keeping sun and rain out. However, the most salient feature of the jaali are its perforations, which cool the air as it comes in.

Here’s an experiment. Open your mouth and blow on the back of your hand. Now, do the same thing while bringing your lips closer together, as if you’re going to whistle. The difference in temperature of the air being blown should be obvious; pursed lips blow cooler air!

This is a very simple application of the Venturi effect.

When air passes through a constriction, it gains velocity, which is offset by a loss of pressure. As pressure and temperature are directly related, this further results in a drop in temperature. Perforations in the jaali screen act as miniature orifices, choking the flow of air and reducing its temperature in the process.

The reduced temperature and increased velocity help an interior space reach acceptable thermal comfort temperatures. Due to intricate designs and the use of materials like stone and marble, jaalis were primarily used in more affluent households. Popular examples of jaali are found in Indo-Islamic architecture, such as the Taj Mahal (Agra, India) and Hawa Mahal (Jaipur, India).

Thick Walls With Radiant Cooling

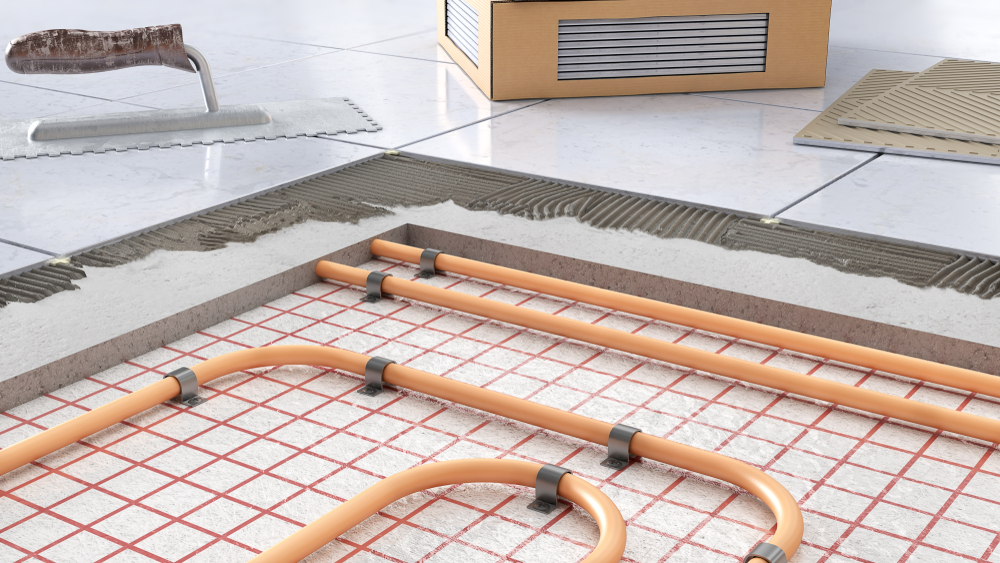

Radiant cooling refers to the loss of heat from a body to its surroundings by means of radiation. Thicker walls in establishments like fortresses and castles have greater thermal inertia. That is to say, they can absorb more heat that is radiated by bodies and objects confined within them.

Thicker walls are slow to absorb and release heat, making for uncomfortable conditions at night. Thus, the walls and floors of old palaces often featured concealed and exposed channels for water to pass through. The flowing water takes the heat from the walls away with it, helping to keep the walls cool.

Modern techniques utilizing radiant cooling feature pipes inside walls carrying chilled water. This alone has been observed to reduce the HVAC costs of establishments by as much as 25% or more. Infosys, an IT giant in India, is renowned for adopting radiant cooling as an alternative to conventional HVAC.

Shading Of The House

Well-designed exterior shading of the house cuts off the harsh sunlight coming in during the afternoon. This reduces the heat gain on the exterior surfaces of the house (windows and blank walls) and also ensures ambient temperatures in semi-open and outdoor areas of the house.

Initially, this shading was done with trees, but as techniques evolved, the shading could be achieved by an opaque slab running through the house (seen above modern windows), extended balconies, and perforated wooden shades called pergolas. Examples of this are seen in Mughal architecture with jharokhas, which provide a separation of space, reducing the temperature of the room inside.

Aqueducts And Water Features

Aqueducts are elaborate networks of underground and surface channels dedicated to an area’s water supply. Commissioned by the Romans, they supplied water for both domestic and temperature regulation purposes. Features like pools and fountains that were common to architecture of that period received water from these aqueducts.

They also made for simple heat exchangers, cooling hot air as it entered from the front of the courtyard. Hot air would blow over the pools and through fountains, losing its heat to the water upon contact. This is known as evaporative cooling. Water fountains, screens and pools were either used by themselves, or in conjunction with other methods for cooling.

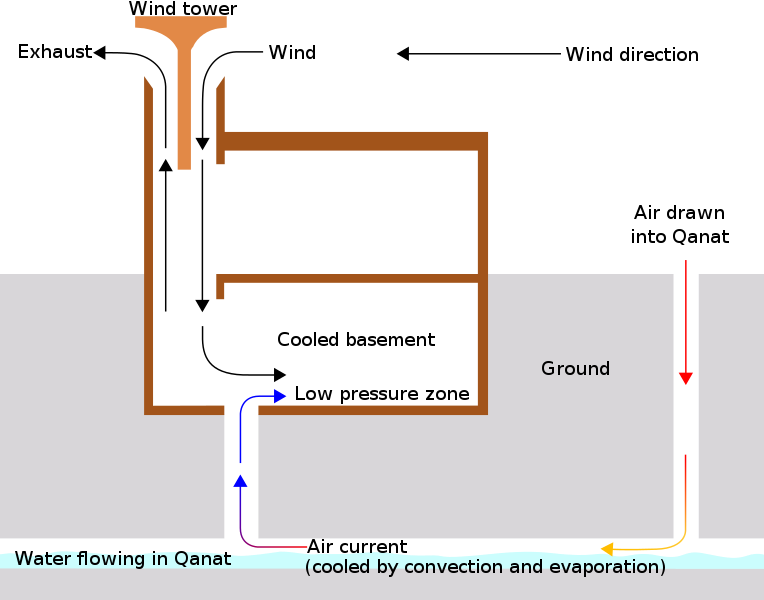

Wind Catchers

Wind catchers originated in the deserts of the Middle East. They are a great example of how hot arid air can be manipulated to keep houses cool. As the name suggests, wind catchers are structural elements jutting out of a house, much like a chimney.

These structures have scoops and openings that face the wind, directing it into the house. A portion of the wind’s heat gets absorbed by the walls of the house due to thermal inertia. The bottom of the wind catcher, located inside the house, routes wind through moist screens and dust filters to further reduce temperature.

Both elite and common households made use of wind catchers. Local climatic conditions played a huge role in their design and orientation, making them unique to their regions. A great example of traditional wind catchers is the Borujerdi House in Iran.

Step Wells

Step wells emerged in arid regions of Gujarat and Rajasthan, India for the harvesting and storage of water all year round. They are known for their peculiar, reverse architecture of staircases, descending into a well several stories below.

Step wells had their own microclimate; the bottom of the step well, near the water reservoir, was several degrees cooler than the surface. The funnel-like cross section of step wells prevented any excessive loss of water to evaporation, while also providing shade from the harsh sun.

It is no wonder that step wells became social gathering spots that not only provided water, but a respite from inclement heat in arid regions. While step wells are mostly defunct, architects and designers are seeking to revive them as modern, energy-efficient solutions for water storage and temperature control. Some great examples of step wells include Agrasen Ki Baoli, Delhi and Adalaj Ni Vav, Ahmedabad, India.

Reed Mats With Trickling Water

While the intricate jaalis were restricted to the elite, common households used reed mat curtains made of vetiver leaf. Known for its earthy fragrance, vetiver root was dried and woven into mats and curtains. Reed mats with trickling water are another example of evaporative cooling.

In the summer months, water sprinkled over the mat would quickly spread throughout due to capillary action. This water would utilize heat from the outside air and evaporate, cooling the air before it entered the room. Needless to say, these mats had to be dampened repeatedly to work effectively. Interestingly, reed mats are still used as decorative elements in many modern households.

A Final Word

Here’s a ‘cool’ hack for you. In the absence of an air conditioner or fan, you can cool yourself off quite easily. The trick is to cool your pulse points, such as the wrists and the sides of the neck, using water or even a wet cloth.

As energy consumption increases worldwide, architects and designers are turning more and more often to ancient architecture for inspiration on sustainability. How the ancient will fuse with the modern will be quite interesting to see!

References (click to expand)

- A Shukla —. Assessment of Venturi Effect for Enhancing Natural Ventilation .... The International Building Performance Simulation Association

- Significance of Jaali on Thermal Performance of Buildings. irjet.net

- Khan, Y., Khare, V. R., Mathur, J., & Bhandari, M. (2015, June). Performance evaluation of radiant cooling system integrated with air system under different operational strategies. Energy and Buildings. Elsevier BV.

- Economic Assessment of Radiant Cooling Technique in Air .... ijrte.org

- A Singh. Study of Ancient Stepwells in India - IJRESM. ijresm.com

- Stepwell – The Water Architecture of India - Tehqeeqat. tehqeeqat.org

- History of Air Conditioning - Department of Energy. The United States Department of Energy

- Roman Aqueducts - National Geographic Society. National Geographic

- (PDF) INDIGENOUS ARCHITECTURE AND NATURAL COOLING - www.researchgate.net