Table of Contents (click to expand)

Gut bacteria help the body break down carbohydrates, especially resistant starch, which is difficult for our digestive systems to process. Gut bacteria also provides us with critical nutrients, like vitamin K.

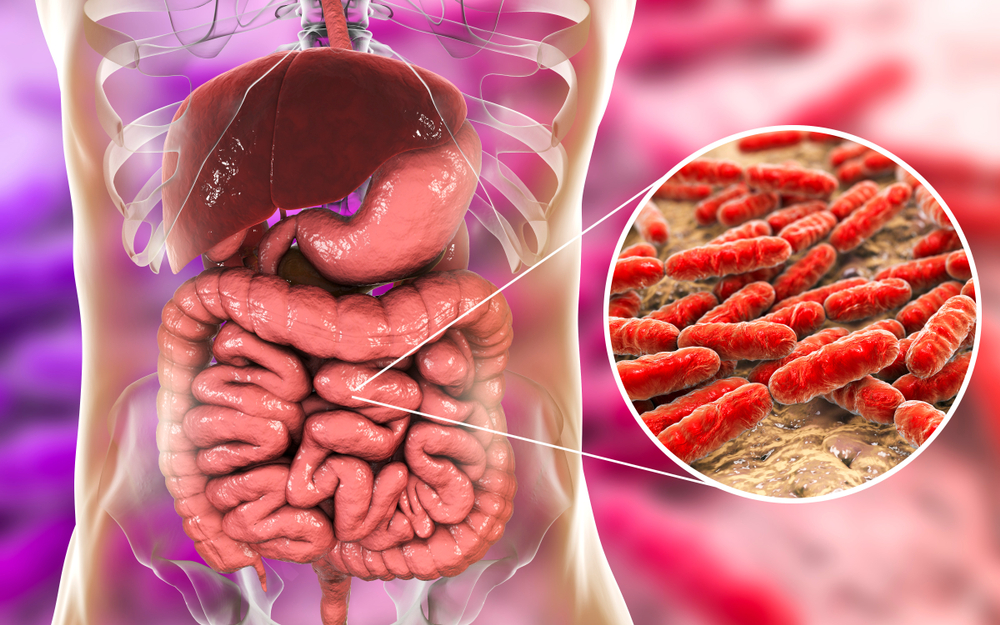

There are about 100 trillion bacteria residing in our gut. That means there are 100,000,000,000,000 of these tiny living things hanging out inside us, and to put it in perspective, that is more than 1 million times greater than the world’s population!

Gut bacteria play a pivotal role in our bodily functions and help keep us healthy. One of their main roles is to help us digest food and properly absorb the nutrients from our diet. However, where do they come from and how do they help in digestion? That’s what we’re about to find out.

Recommended Video for you:

Gut Bacteria Comes From The Environment

It is hypothesized that bacteria begin to enter and settle in our guts at birth, but other studies, such as this one, found bacteria in the placenta as well, suggesting that gut bacteria could be present even before we are born.

Every moment of every day, we’re exposed to countless numbers of bacteria through the water we drink, the food we eat, and the air we breathe. These bacteria enter our bodies, fully prepared to grow their own communities and make a nice little home for themselves inside our bodies.

On average, there are around 300-500 species of bacteria in our gut that scavenge off the food we eat.

The Functions Of Gut Bacteria

Gut bacteria have a variety of functions in our body, such as:

- Breaking down food molecules and helping in metabolic reactions

- Strengthening the walls of our intestines

- Boosting our immune system

- Maintaining the internal gut environment

- Synthesizing important vitamins and amino acids

That being said, the functions we are interested in talking about today are those involved in digestion.

Bacteria Help Break Down Food

We chew our food and swallow it, moving it down to our stomach where acids further break it into simpler components. After that, the nutrients and water are absorbed by our intestines; whatever remains comes out as fecal matter (poop!).

This may sound fairly straightforward, but it’s not that simple. Around 60 tons of food pass through a single person’s body in their lifetime. That’s the equivalent of about 10 elephants! Surely some help is required to digest so much food.

Scientists have realized that we’re only able to digest our food with some help from our intestinal tenants. In fact, there are some nutrients that we wouldn’t be able to digest and absorb without them.

Polysaccharides

One of these food molecule types is complex sugars, known as polysaccharides. Polysaccharides are large sugar molecules that are abundantly present in both plants and animals. Examples of polysaccharides in plants are starch and cellulose. In animals, polysaccharides are present as glycogen, which is abundantly present in animal liver and muscles.

The bacteria in our gut break down the polysaccharides into simple glucose molecules, which can then be easily absorbed by our intestines.

To summarize, they break down the compounds in our food that we can’t handle alone, transforming it into fuel that our bodies can use to power themselves.

Resistant Starch

An example of a tough-to-digest sugar is resistant starch. Anywhere between 2-20% of dietary starch that we consume cannot be digested by our body’s enzymes. Such starch is known as resistant starch. Also, some of our dietary starch is not digestible because it is held inside a seed that protects it from the body’s enzymes and acids. Common foods that contain resistant starch are fried rice, potato salad, and corn.

Fortunately, thanks to our gut bacteria, this starch doesn’t go to waste. Certain strains of gut bacteria like Ruminococcus bromii specialize in breaking down tougher forms of starch. These bacteria, along with a few other types, have glycoside hydrolases, which are enzymes that digest complex sugars.

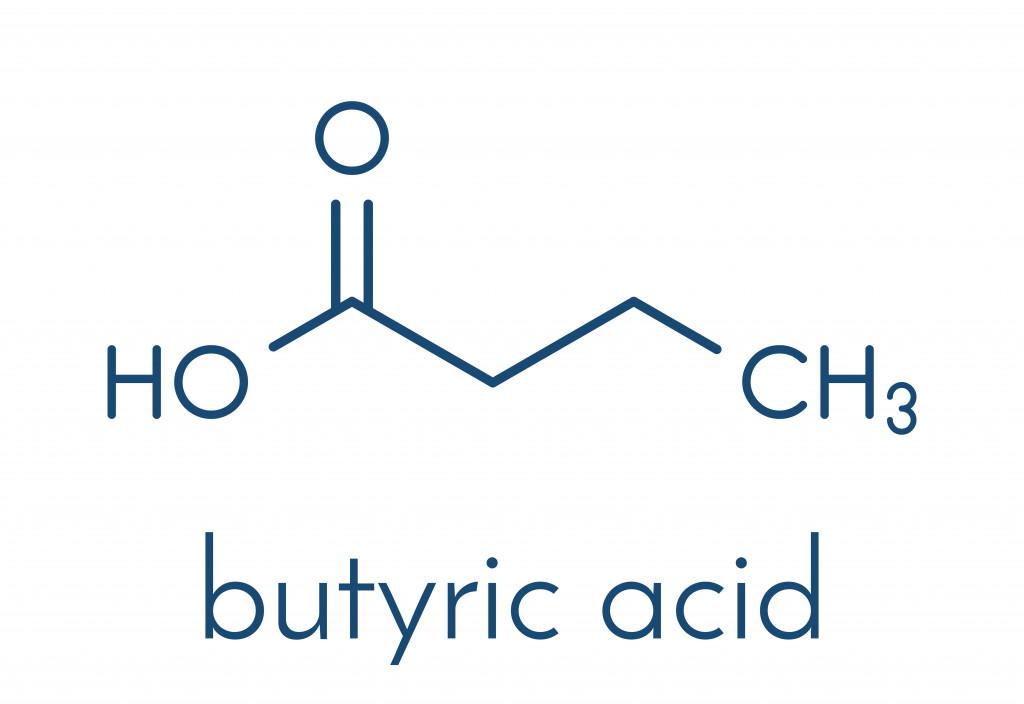

Such bacteria break down the resistant starch in our system for themselves, releasing fats, or more specifically Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs for short) as byproducts. These short-chain fatty acids have brain-boosting properties that strengthen our brains and their neurons.

Apart from glycoside hydrolase, the trillions of gut bacteria in our body also produce countless enzymes that further help to break down our food. Many kinds of sugar-breaking enzymes are produced, such as polysaccharide lyase and carbohydrate esterase.

One side effect of bacteria breaking down our food is the production of gas. That’s right, smelly stinky farts are the result of methane produced by bacterial fermentation. However, not all bacteria give off gas as a byproduct, so if you do have a gas problem, it could be that you have less of the gut bacteria that don’t produce methane.

Bacteria Break Down Our Food And Release Vitamins

We humans cannot make certain vitamins by ourselves, such as vitamin A, B1, B2, B5, B6, B7, B9, B12, E and K. Therefore, we need a little help from our microscopic friends, especially to produce the B group vitamins and vitamin K.

The gut bacteria ferment the food we eat and obtain energy from it, which they use to make enzymes and other important proteins that eventually become essential vitamins for their own survival. However, the bacteria are generous enough to make extra, which is then released into our gut and absorbed by our intestine. Essentially, we have our gut bacteria to thank for making some of the essential nutrients that our bodies need to stay fit and healthy.

A Final Word

One exciting field of gut bacteria research relates to analyzing all the bioactive molecules the bacteria release (such as SCFAs and vitamins) and figuring out exactly how the bacteria make it.

Once understood, the hope is to push bacteria to secrete more beneficial compounds, either by using drugs or dietary changes. However, there are hundreds of different types of bacteria in the gut, and studying them individually is quite time-consuming and costly.

The old adage of “You are what you eat” feels pretty appropriate here! From the endless bacteria that live inside us, we can favor the growth of some bacteria over others by controlling what we eat. So, when you choose to have a bacon-and-cheese sandwich over a fruit salad, you increase the number of bacteria that love the contents of the sandwich, but the poor fruit-loving bacteria are more likely to starve and die.

During this new year, let’s take a moment to appreciate how much work our gut bacteria actually does for us. The best way to do this is to eat clean and fresh food to support the good bacteria we already have inside. A sugary treat is fine once in a while, but it shouldn’t regularly feature on the menu.

After all, if we have bad gut bacteria growing inside us, it can lead to many stomach problems, and may even prevent us from getting all the healthy nutrients from our food.

What’s even more interesting is that gut bacteria can make us feel certain cravings in order to get us to eat the food they want, but that’s a story for another time…

References (click to expand)

- Sears, C. L. (2005, October). A dynamic partnership: Celebrating our gut flora. Anaerobe. Elsevier BV.

- Schluter, J., & Foster, K. R. (2012, November 20). The Evolution of Mutualism in Gut Microbiota Via Host Epithelial Selection. (S. P. Ellner, Ed.), PLoS Biology. Public Library of Science (PLoS).

- Valdes, A. M., Walter, J., Segal, E., & Spector, T. D. (2018, June 13). Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. Bmj. BMJ.

- Thursby, E., & Juge, N. (2017, May 16). Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochemical Journal. Portland Press Ltd.

- Ze, X., Duncan, S. H., Louis, P., & Flint, H. J. (2012, February 16). Ruminococcus bromii is a keystone species for the degradation of resistant starch in the human colon. The ISME Journal. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- (2013) Gut Bacteria in Health and Disease - PMC - NCBI. The National Center for Biotechnology Information

- Cerqueira, F. M., Photenhauer, A. L., Pollet, R. M., Brown, H. A., & Koropatkin, N. M. (2020, February). Starch Digestion by Gut Bacteria: Crowdsourcing for Carbs. Trends in Microbiology. Elsevier BV.

- David, L. A., Maurice, C. F., Carmody, R. N., Gootenberg, D. B., Button, J. E., Wolfe, B. E., … Turnbaugh, P. J. (2013, December 11). Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.