Mosquito repellents have long been a necessary item in our first-aid kits and camping gear. They have a very unique way of bringing about the desired effect and keeping us free of bites!

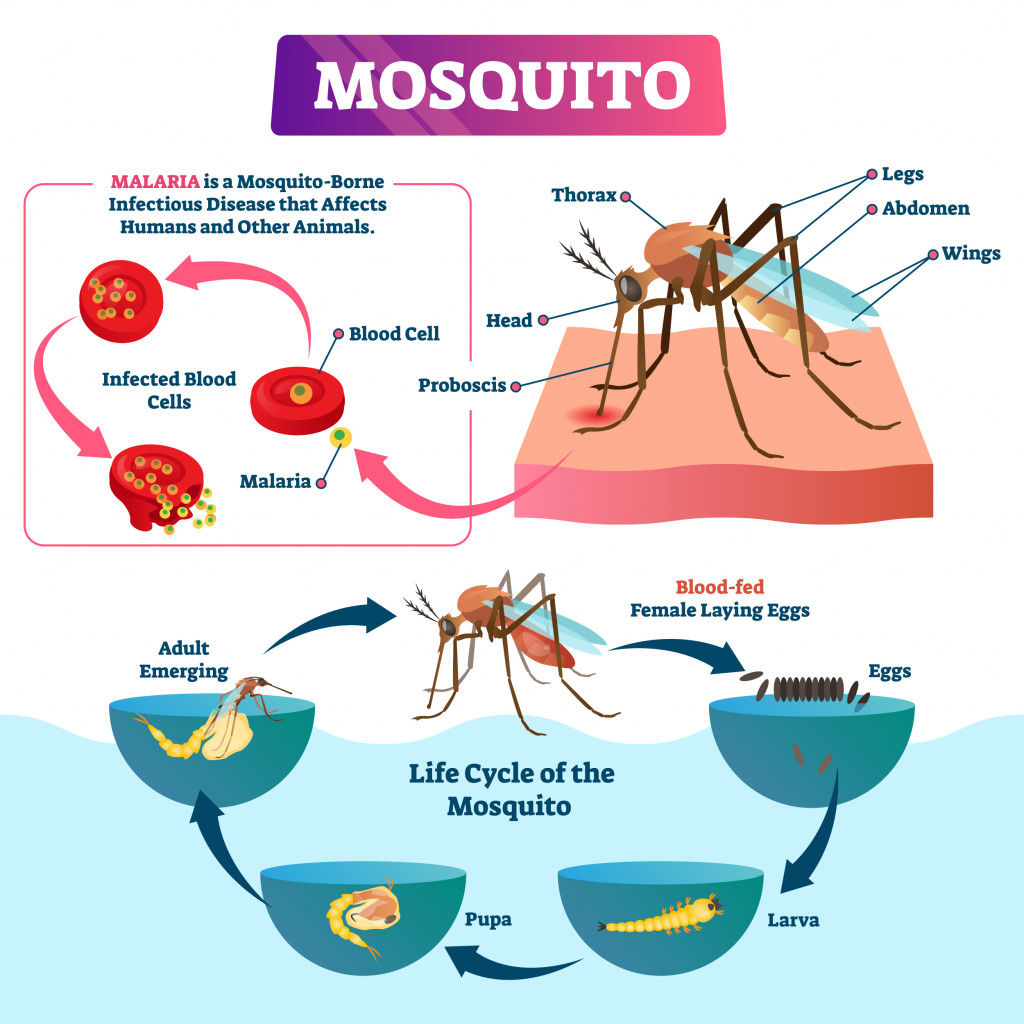

This might come as a shock to you, but the mosquito is the deadliest animal on Earth! (approximately 750,000 deaths per year).

The only instinct we know of when we see a mosquito is to squash it. Squashing mosquitoes is unpleasant, and you can’t go through the entire day spraying repellents, swinging mosquito racquets, or burning coils.

Instead, you probably choose to apply mosquito repellent on your skin or switch on a repellent vaporizer, then go about your work without worries. When you forget to use it, however, mosquitoes find your blood like Liam Neeson in Taken. At that point, you might wonder, “How did the mosquito find me in the first place?”

Recommended Video for you:

How Do Mosquitoes Sense The Presence Of Humans?

Only female mosquitoes are attracted to warm-blooded hosts, as our blood has the required nutrients to complete its reproductive cycle. Male mosquitoes, on the other hand, feed on plant sap and nectar.

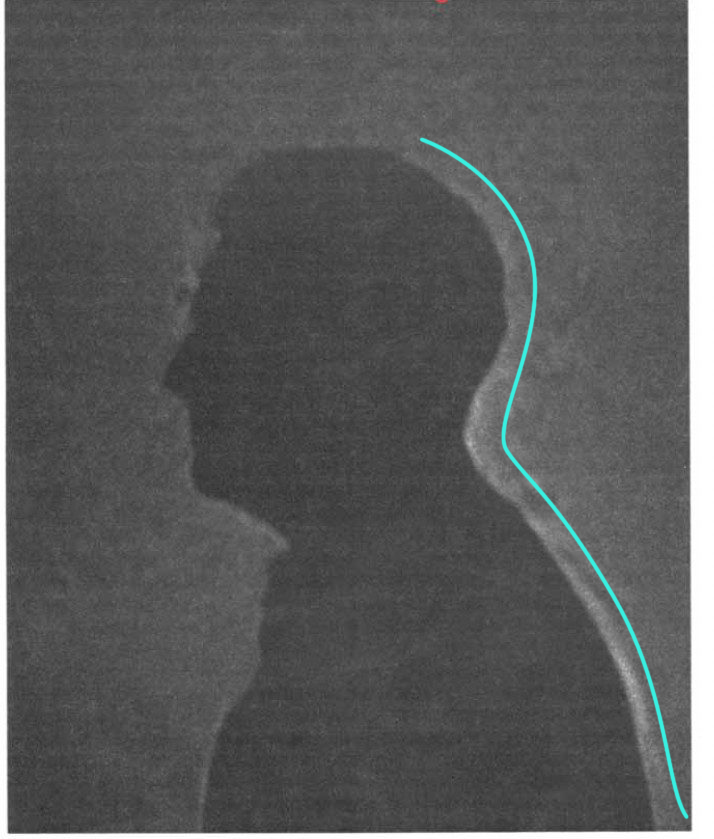

Mosquitoes don’t rely on vision or mechanical stimulation to find their blood-filled hosts. Instead, they have delicate sensory receptors on their antennae that help them in the process. They mainly sense the level of carbon dioxide and warm convections emanating from our bodies.

Upon sensing carbon dioxide, they become alert and look for the nearby host. Humans, being warm-blooded animals, also have a natural warm convection of airflow around them, which attracts mosquitoes. This convection pattern helps mosquitoes distinguish between lifeless objects and warm, living animals.

If you sweat more, you are likely to attract more mosquitoes! The reason for this is that your skin temperature rises, and your warm air convection thickens. Secondly, mosquitoes are quite responsive to lactic acid, which is released by our bodies when we sweat.

What Do Mosquito Repellents Do To Mosquitoes?

There are many different species of mosquitoes (yellow fever mosquito, malaria mosquito, dengue, etc.), and repellents available in the market are not species-specific.

Thus, they work in a simpler way, targeting some commonalities among all mosquitoes.

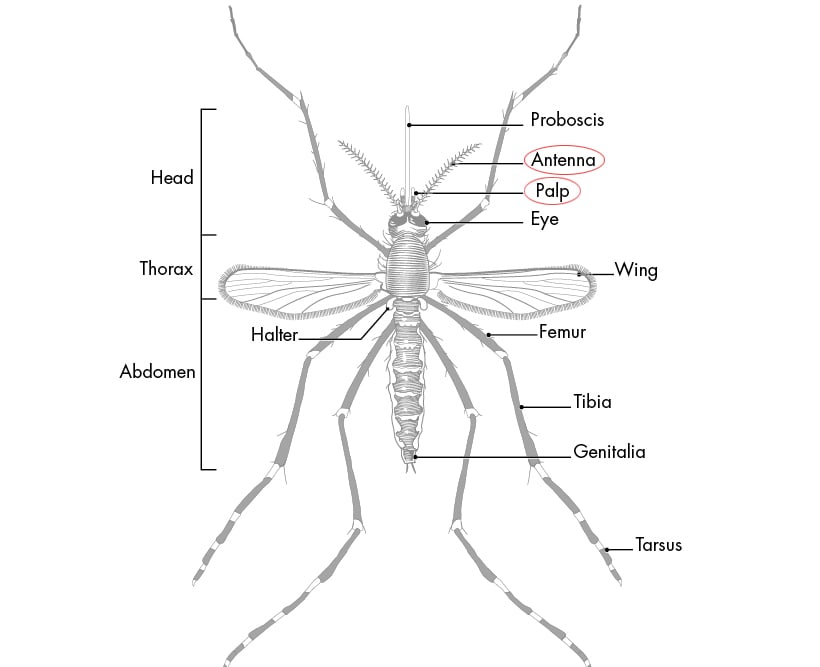

One such commonality is their sensory receptors. Mosquitoes rely on sensory stimuli for detecting hosts; their olfactory and gustatory receptors work to achieve this. These receptors are on their antennae and maxillary palps.

The repellents mainly target these receptors and their neurons to interfere with the signaling process. Interfering with the signaling process means not pointing mosquitoes in the right direction; for example, the repellent might activate unwanted receptors or inhibit the selected receptors.

This response goes against the usual state of being for the mosquito, as its central nervous system is being fooled and believes that there is no host, so they fly right past it.

Remember that the objective of a repellent is not to let the insect land on humans at all; a repellent that would kill them after they landed would require different chemicals that are not good for the skin.

What Are Mosquito Repellents Made Of?

Mosquito repellents on the market go through several checks and tests to ensure that they are skin-friendly and have the required level of effectiveness. We know that repellents work by meddling with the sensory receptors of the mosquito, but how exactly these repellents interact with specific neurons and the detailed response of those neurons remains under study.

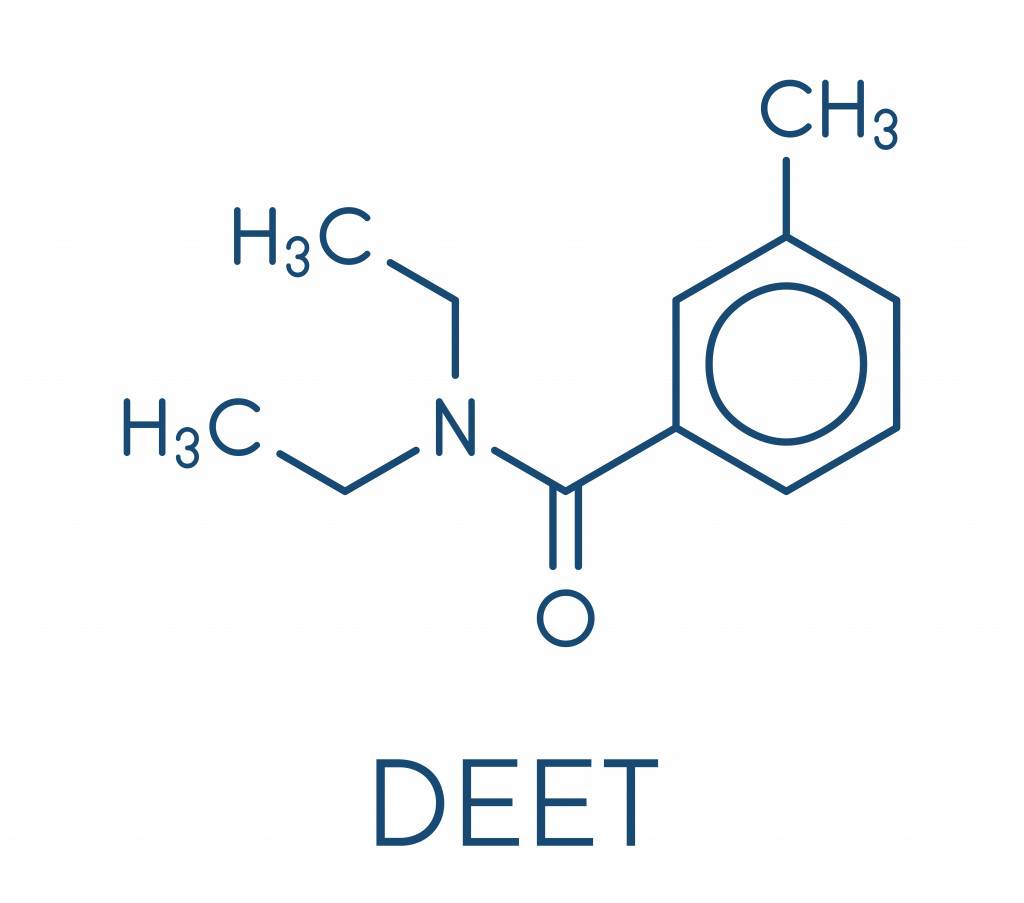

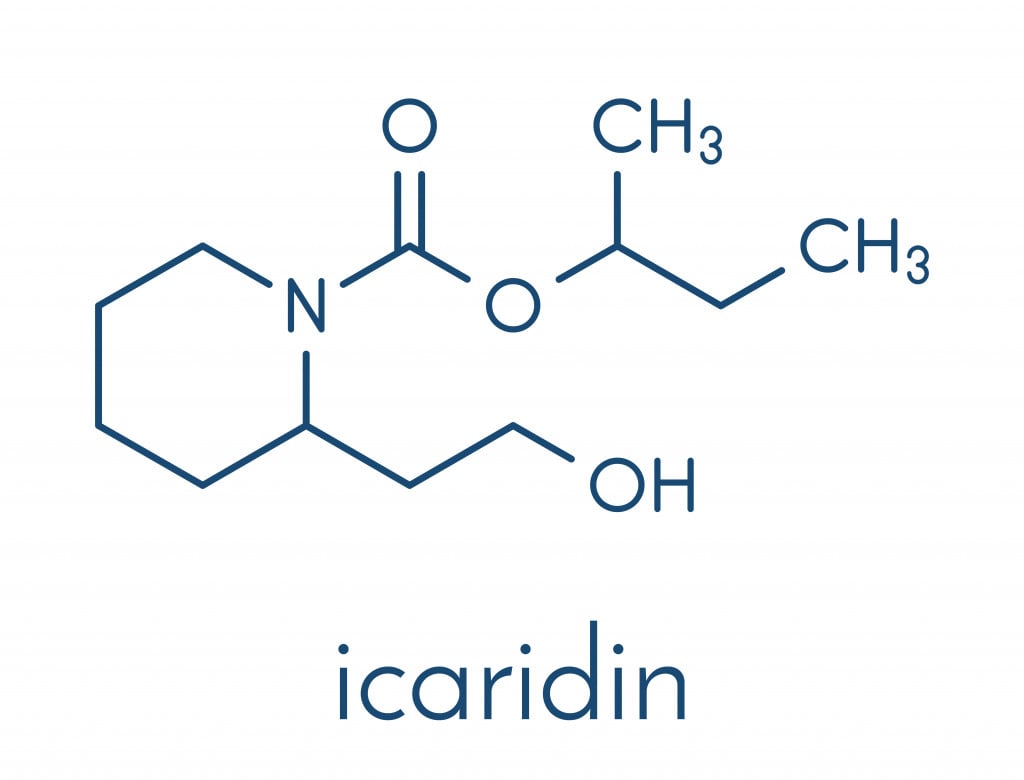

Specific functional groups in the chemical structure of repellents are favored over others; for example, amides, piperidines and diols have good repellency action.

DEET – (N, N-Diethyltoluamide)

This chemical has been the most effective repellent and protects against many arthropods, including mosquitoes. It has been used since 1957 and is still a significant component in modern mosquito repellents. It has minimal toxicity or safety issues and is best used for topical application.

Picaridin

Also known as Saltidin or Icaridin, this chemical belongs to the piperidine class of compounds. Picaridin is also a good repellent against many arthropods and is odorless, making it more human-friendly. It has been used since 2005 and is available in many forms, including aerosols, ointment and wipes. It can also be applied to clothes.

Apart from these chemicals, some repellents contain non-conventional chemical classes like phthalates, mandelic acid esters and phenols.

Natural Mosquito Repellents

One might be skeptical about using the synthetic chemicals mentioned above, given that they might cause unwanted skin infections or have other side effects. Hence, we opt for naturally available mosquito repellents.

Mosquitoes were on Earth long before our evolution started, so many of our ancestors would have needed a remedy for mosquitoes, as malaria used to be a plague in those times too. Indeed, we had such remedies and still use them today.

Plants are the natural source of mosquito repellents, producing them to repel mosquitoes who siphon their nectar. Some examples include neem leaves, clove (Eugenol), camphor, lemon eucalyptus (limonene) oil, cedar, lavender, and many more.

The most effective among these is ‘Citronellal’, which is present in many different products. Citronellal comes from the plant citronella (Cymbopogan nardus L.) and belongs to the chemical class of terpenes. Due to the discovery of citronellal as a mosquito repellent, terpenes have been heavily studied for their repellency effect.

These natural repellents might not be effective for as long as their synthetic counterparts, but they have proven effective and have been passed on as home remedies over many generations. Applying more repellent doesn’t mean more protection from increased concentration; it simply means that the effect lasts longer.

Conclusion

Mosquitoes are everywhere, especially in humid conditions where our skin temperature is high, making it easy for them to detect us. Repellents simply disturb their sensory sites and misdirect them into believing there is no host nearby. Such repellency can be achieved by synthetic products or natural compounds that evolved to display such an effect.

References (click to expand)

- Wright, R. H. (1975, July). Why Mosquito Repellents Repel. Scientific American. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Dickens, J. C., & Bohbot, J. D. (2013, July). Mini review: Mode of action of mosquito repellents. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology. Elsevier BV.

- Islam, J., Zaman, K., Duarah, S., Raju, P. S., & Chattopadhyay, P. (2017, March). Mosquito repellents: An insight into the chronological perspectives and novel discoveries. Acta Tropica. Elsevier BV.

- Islam, J., Zaman, K., Duarah, S., Raju, P. S., & Chattopadhyay, P. (2017, March). Mosquito repellents: An insight into the chronological perspectives and novel discoveries. Acta Tropica. Elsevier BV.

- da Silva, M. R. M., & Ricci-Júnior, E. (2020, December). An approach to natural insect repellent formulations: from basic research to technological development. Acta Tropica. Elsevier BV.