Table of Contents (click to expand)

Train wheels are not entirely conical, but they are not perfectly cylindrical either. The most critical advantage that slightly conical wheels (in trains) have is that they can rotate at slightly different speeds, while cylindrical ones can’t (at least not as smoothly as conical ones).

When an automobile (that runs on four or more wheels) takes a turn, the wheels on the outside (during the turn) must travel a slightly greater distance than the wheels on the inside.

This is important, because if this were not the case, we could never have ‘stable’ cars that could reliably maneuver a turn while staying on the road. However, how do you make two wheels, which are of the same diameter and attached to the same axle, cover different distances?

This is where automobiles’ axles enter the scene.

Recommended Video for you:

Axle

An axle is a central shaft for a rotating wheel or gear. In simple words, the axle is a rod that goes through the vehicle’s wheels, thus letting the latter turn. Axles, needless to say, are a critical component of most wheeled vehicles. They not only transmit driving torque to wheels and maintain the wheels’ position with respect to each other and the vehicle body, but also bear the weight of the vehicle and any cargo.

Axles come in different systems; in some wheeled vehicles, they may rotate with the wheels fixed to them (or the vehicle). These axles have a part – a differential – which enables the outer wheel to go a little more than the inner wheel, which facilitates a stable, ‘grounded’ drive.

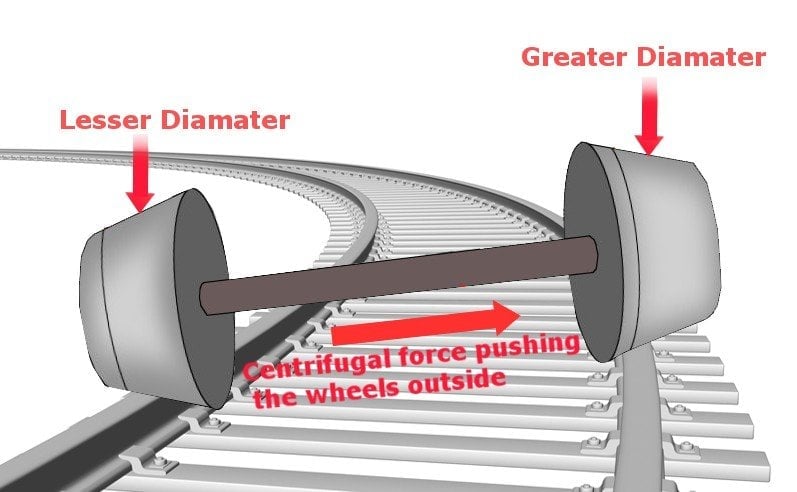

Trains, just like cars, also have wheels that are of the same diameter, which means that they also have to deal with the same situation when they maneuver a turn, i.e., their outer wheels need to travel a bit further than the inner ones, lest the train get derailed.

In the case of cars, this situation is handled with the help of intelligently-designed axles, but how is it tackled when long, heavy and large trains (with hundreds of wheels) are in question?

Train Wheels

A train wheel is a type of wheel that’s especially designed to run on metallic railway tracks. Also referred to as a rail wheel, it’s either cast or forged and is treated with heat to acquire a specific, desired toughness.

Now, you may have seen trains countless times in your life, but have you ever really paid attention to their wheels? A casual glance at the wheels of a train will tell you that they are circular, just like other standard wheels. I used to think that train wheels were perfect circles too… but they’re not!

Train Wheels’ Conical Shape

If you don’t know already, you might be a little surprised to learn that many (not all) trains’ wheels are not perfectly cylindrical; they are, in fact, conical!

Train wheels are not entirely conical, of course, otherwise they would be unable to run (duh!), but they are actually not perfectly cylindrical either.

The most critical advantage that slightly conical wheels (in trains) have is that they can rotate at slightly different speeds, while cylindrical ones can’t (at least not as smoothly as conical ones).

You see, when a conical wheel turns, it slides to the larger part of the cone on the outside wheel and the smaller part on the inside wheel.

The upshot is that that the two wheels still turn at the same rate, but their radii are different. Here’s an animation that will help you visualize this better:

On the other hand, when trains with cylindrical wheels maneuver a turn and consequently attempt to run at slightly different speeds, they slip/slide, creating a deafening screeching sound. Rail systems like the BART don’t have conical wheels, and as such, are notorious for being very loud when they take turns.

Here’s an interesting video that explains the mechanism behind the turning of train wheels in detail:

References (click to expand)

- Teaching Simple Machines. Illinois State University

- Wheel/axle - www.users.miamioh.edu

- links - atlantis.coe.uh.edu

- New wheel tech quiets screeching rails | bart.gov. Bay Area Rapid Transit

- Sheng, X., Liu, Y., & Zhou, X. (2016, September). The response of a high-speed train wheel to a harmonic wheel-rail force. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing.

- HECKL, M. A., & ABRAHAMS, I. D. (2000, January). Curve Squeal Of Train Wheels, Part 1: Mathematical Model For Its Generation. Journal of Sound and Vibration. Elsevier BV.

- Broom, M. L., & Smart, G. W. (1990, July). The Design, Manufacture and Assembly of the Wheelset for the British Rail Class 91, 25 Kv, 225 Km/H Locomotive. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part F: Journal of Rail and Rapid Transit. SAGE Publications.