Table of Contents (click to expand)

A Barr Body is a compacted, inactivated X chromosome present in the cell nucleus of female individuals that provide dosage compensation for the extra X chromosome.

A ‘Barr Body’ is not related to the practice of law, but is instead a biological term. It refers to the condensed, inactivated X chromosome present in the cell nucleus of female individuals.

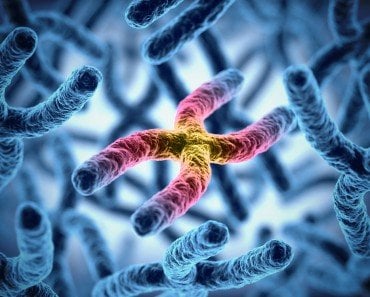

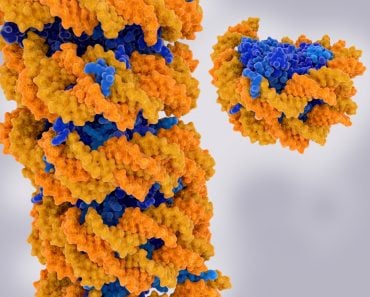

A chromosome consists of a single long strand of DNA molecules packaged into a thread-like structure. All the chromosomes in an organism comprise the entirety of its genetic information. A process called transcription is required to interpret this genetic information, which is present in short readable DNA sentences called genes, to form functional proteins.

Euchromatin chromosome are only lightly condensed, which allows them to be transcribed into proteins, whereas, heterochromatin chromosomes are tightly packed, which makes them transcriptionally inactive.

Recommended Video for you:

Barr Body: The Secret To Female Survival

Usually, having either less than or more than the normal number of chromosomes (46 for humans) in a cell can be fatal. In most situations, this would cause an embryo to die during early development.

Yet, there is a crucial chromosomal difference between males and females, particularly in species that have the XY sex-determination. For example, in humans, males are heterogametic, having XY sex chromosomes, while females are homogametic, with two sets of the X chromosome (XX).

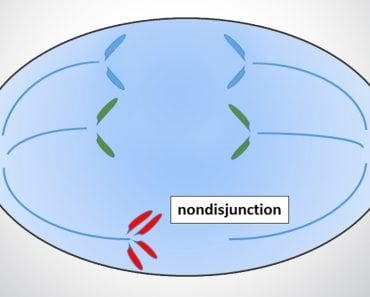

One X chromosome provides the normal amount of gene dosage required for the cell to properly function. That’s why males are fine with only one X chromosome. Females, however, have an extra X chromosome, instead of the Y chromosome. This doubles the amount of X-linked gene activity. To compensate for the extra X chromosome, cells render one of the two X chromosomes inactive in a process called lyonization or X-inactivation.

Lyonization

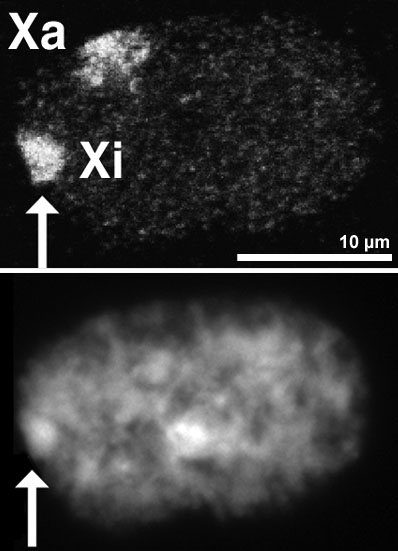

When the embryo is at the blastular stage (>100 cells in humans), one of the X chromosomes becomes transcriptionally inactive due to chromatin condensation. The X chromosome becomes a supercoiled, highly condensed mass and is thus unable to transcribe genes, rendering it inactive. This inactive X chromosome looks like a darkly stained body attached to the nuclear membrane and is called a Barr Body.

The process of X-inactivation was first described by British geneticist Mary F. Lyon, and the process is named in her honor. She proposed that there was an equal probability of inactivating either the maternal or paternal X chromosome. This meant that this unique and crucial phenomenon of inactivation occurred completely at random!

She also speculated that once whichever X chromosome was inactivated in a cell, all of that cell’s progeny would have the same X chromosome inactivated. This means that females have a mosaic of X chromosome cells. Some cells will have their maternal X chromosome inactive, while other cells will have their paternal X chromosome shut down.

Studies showed that the extra X is inactivated via three mechanisms:

- Methylation of the X-chromosome

- Chromatin protein involvement, which converts the euchromatic (loosely packed) chromosomal DNA to heterochromatic (tightly packed)

- RNA interference induced by the Xist gene on the X chromosome

Research also proved Lyon’s hypothesis in all mammals except marsupials. In marsupials (kangaroos, wombats, koala bears), the paternal X chromosome is always inactivated. Therefore, in a female marsupial, only the maternal X chromosome is functional.

Calico Cat

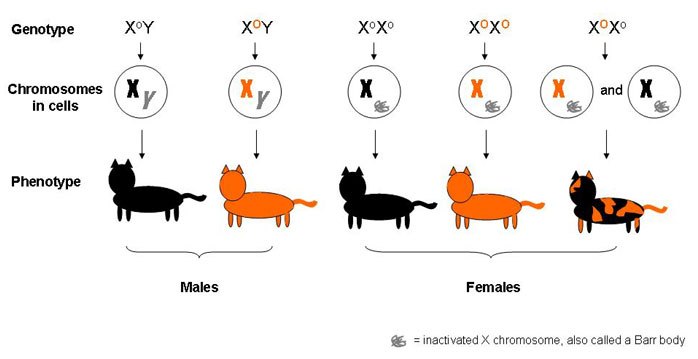

Transcriptional inactivation of the X chromosome was first depicted in cats by a Canadian cytogeneticist, Dr Murray L. Barr. The Barr Body was named after him for making such a significant contribution to the field.

The mosaic coat of a calico coat is a classic visual example of the random nature of X inactivation.

In cats, the X chromosome comprises one of the genes regulating coat color. There are two variants or alleles of this gene. One version codes for orange fur, while the other codes for black fur.

Male cats are either exclusively orange or black, as they receive only one form of the gene on their single X chromosome. Females, on the other hand, can be heterozygous for the allele. They may possess one X chromosome with genes that code for orange fur and another one with genes for black fur.

A heterozygous female will have a mosaic fur of orange and black patches. Lyonization would have occurred in the blastular stage and all the cells derived from a particular blastomere would have the same X chromosome inactivated. Therefore, the skin tissue that arose from cells having the orange-coding X chromosome as a Barr Body will be phenotypically black and vice-versa. This phenomenon gives rise to what is known as mosaic expression.

Interestingly, the ratio between the number of orange patches and black patches cannot be defined due to the random nature of lyonization. Furthermore, no preference for one color has been identified in a particular area of the cat’s body. This adds to the understanding that the inactivation process is completely random.

This also explains why mosaic calico cats are almost always female, though in rare cases, males can inherit an additional X chromosome. This is referred to as Klinefelter syndrome, in which each male cell has XXY sex chromosomes. The extra X chromosome would be inactivated, as in females, but the cat might also face other problems, like sterility.

A Blessing And A Curse

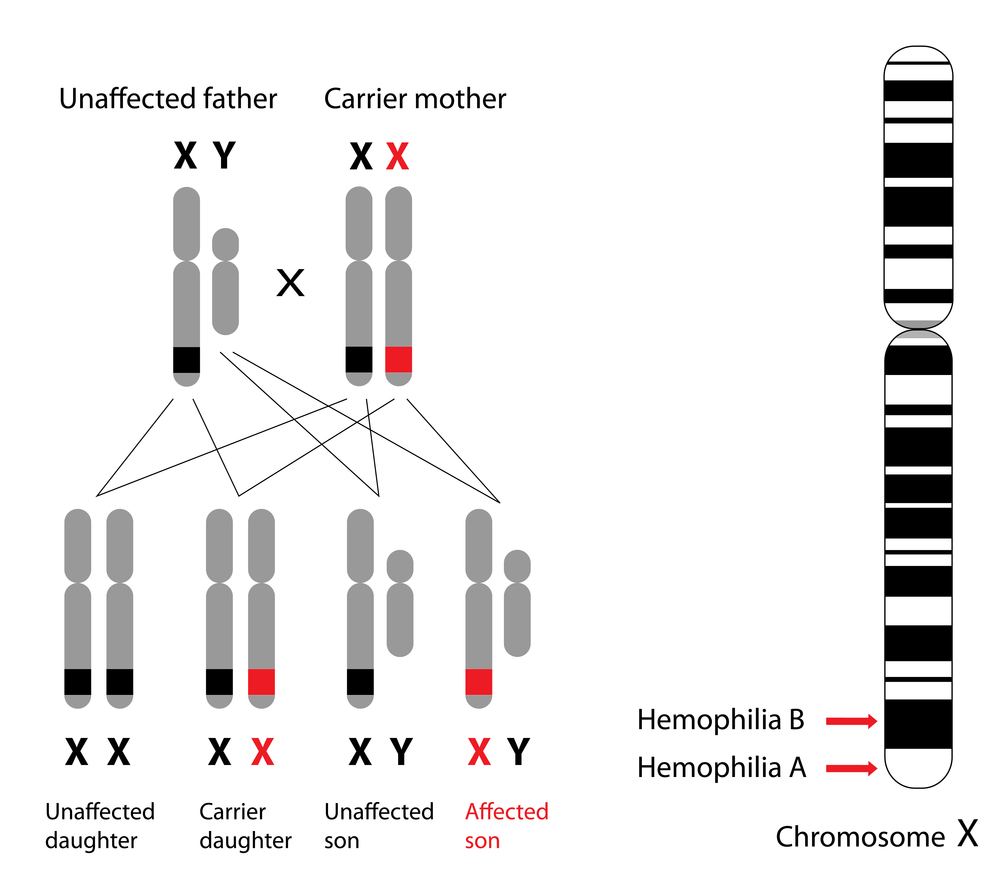

The genes encoded by the X chromosome differ from species to species. For instance, in human beings, the genes responsible for encoding typical clotting factors and for the correct cone photoreceptor pigment are located on the X chromosome. A genetic mutation in the latter causes red-green color blindness, while a mutant gene in the former case may lead to hemophilia (a disorder that causes excessive bleeding due to insufficient levels of clotting factors).

Such genetic disorders are more common in males, as they possess a single X chromosome. If this X chromosome happens to be defective for the genes associated with these conditions, the male will surely be affected.

However, this does not mean that women do not suffer from disorders like hemophilia. A woman who has two defective X chromosomes, that is, she is homozygous for the condition, will suffer from hemophilia. Heterozygous women, on the other hand, can be asymptomatic carriers or even symptomatic carriers.

A typical carrier is expected to have exactly 50% of the level of clotting factors found in the healthy population. Owing to the fact that one X chromosome is defective, while the other is healthy. However, this is not the case.

Due to the random nature of X inactivation, there is a wide range of clotting factor levels in heterozygous females. Most heterozygous females would have enough of the cells with the ‘healthy’ X chromosomes active so as to not suffer from any symptoms. At the other end of the spectrum, it is also possible for most of a woman’s cells to have the ‘healthy’ X chromosome be inactivated. This woman will, unfortunately, suffer from the symptoms of hemophilia, and is called a ‘symptomatic’ carrier.

The presence of Barr Bodies is yet another example of just how intriguing biology is! Apart from intriguing scientists across many fields, Barr Bodies were used in the 1968 Olympics to spot male athletes attempting to pass as females in order to achieve a competitive edge!