Table of Contents (click to expand)

The unsaturated fatty acids present in the drying oils used for painting when in contact with air tend to absorb oxygen and form 3D networks.

A few years ago I received an oil painting from my friend a week after my birthday. It was a beautiful painting of cherries against a winter backdrop with a note that read, “Wanted to send it before your birthday, but the paint just wouldn’t dry.” While I was admiring the painting with my eyes, my chemist brain wandered off─Why is the oil paint drying process so slow? Is something slowing down the evaporation of the solvent?

A quest for the answer revealed two things: 1) Drying of oil paint isn’t actually drying; and 2) The slow drying process helps in the detection of art crime.

Now, before we explore these end points in detail, let’s get a quick refresher on paints.

Recommended Video for you:

How Do Paints Work?

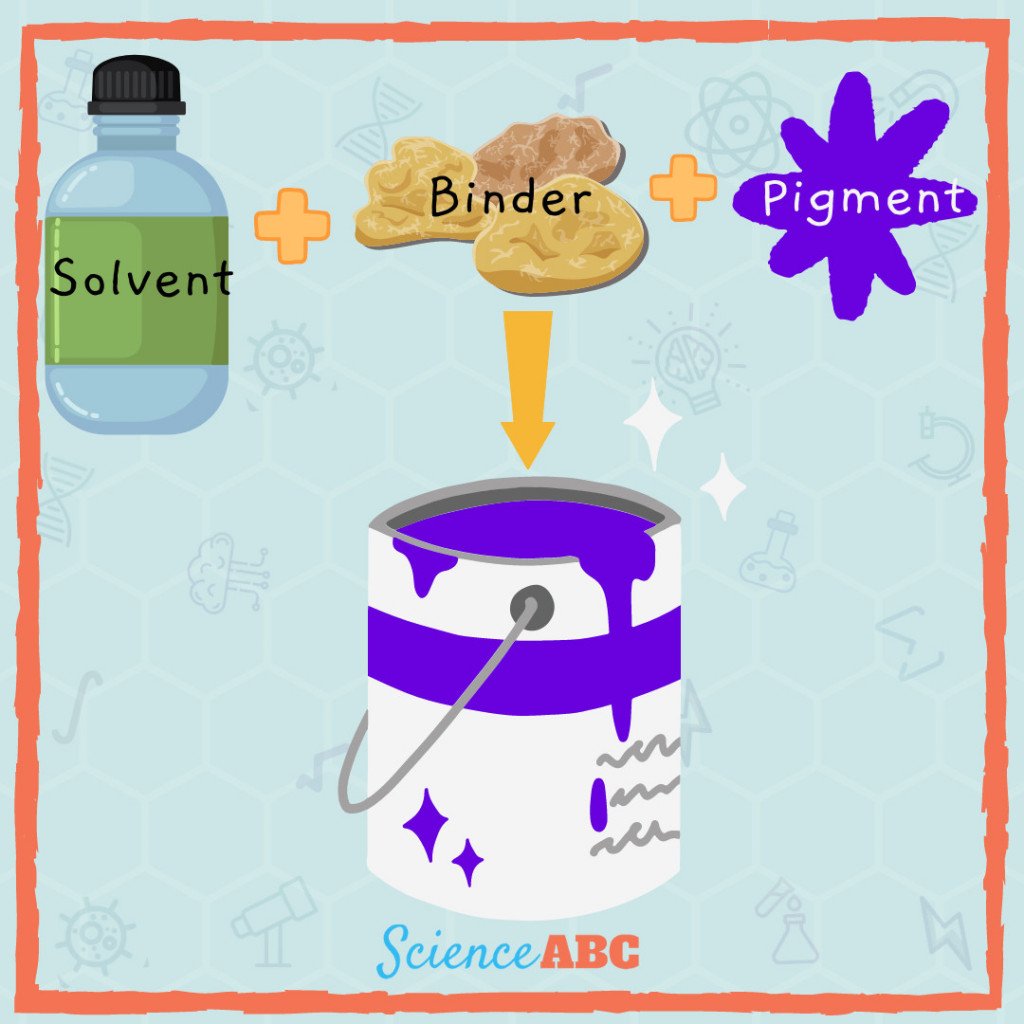

Most paints have three main ingredients: a pigment powder that gives the paint its color, a binder that makes the pigment stick to the surface when painted on, and a solvent or a paint thinner that makes the paint more spreadable. Apart from these components, some paints also have chemical additives for special properties, such as antibacterial, waterproof, glow-in-the-dark, etc.

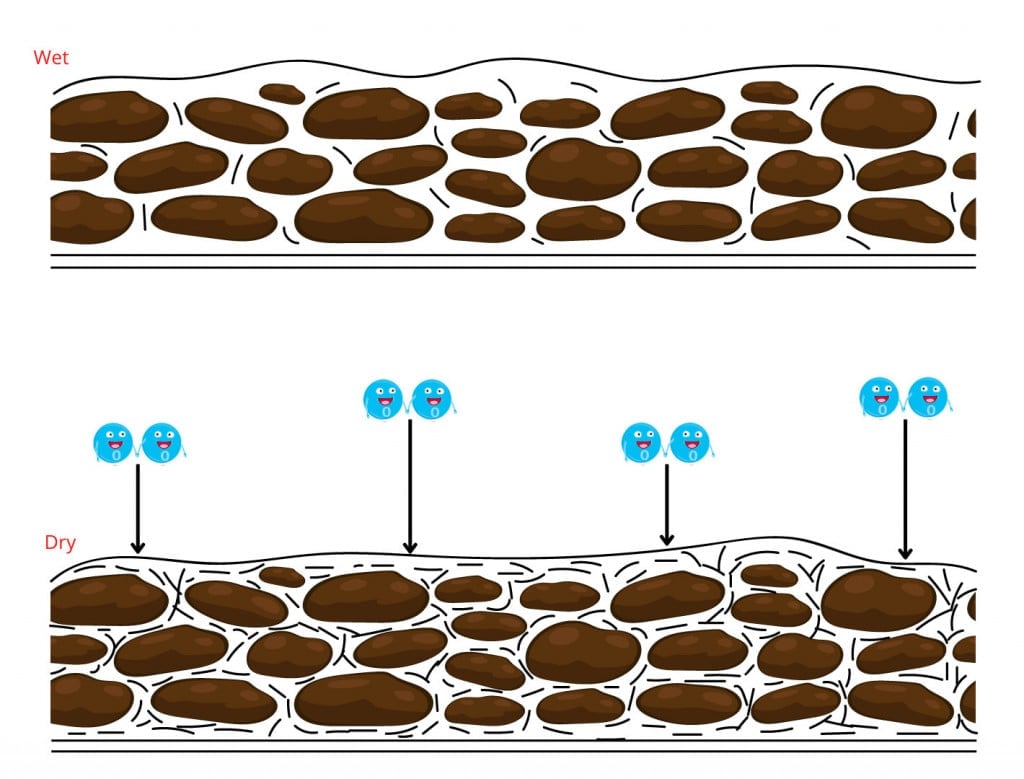

Most paints (excluding oil paints) use volatile organic liquids, such as mineral spirits, acetone, turpentine oil, etc. When such paints are applied on a surface and meet the air, the solvent molecules slowly start escaping from the mixture. This brings the binder-pigments molecules closer, giving us a dry and even layer of paint.

The strong smell of paint drying usually comes from the evaporation of the added solvents. Emulsions for walls or acrylics for wood or fabric can feel dry to the touch within a couple of hours of painting. Here is another article about different types of paints used in art .

How Do Oil Paints Dry?

As mentioned earlier, oil paints do not dry, as drying would involve losing moisture or solvent. Neither of these happens after a surface has been coated with oil paints. The phenomenon responsible for the notorious behavior of oil paints is polymerization.

Oil paints are made by grinding the pigment and oil together into a smooth paste. These paints require a specific type of oil that, after drying, form an elastic layer, and don’t turn rancid and sticky over time. Imagine a painting of a bright meadow smelling like week-old fries forgotten in some corner of your kitchen.

The drying oils used for painting are usually derived from plant sources like linseed, walnut, or poppy. These plant-based oils consist of three main compounds: triglycerides, esters of glycol, and fatty acids. Most of these fatty acids are polyunsaturated, which means they are multiple carbon-carbon double bonds that are ready to react with other chemicals.

After the paint is removed from its container and applied to a surface, the polyunsaturated fatty acids slowly kick into action. They absorb oxygen from the air and undergo free-radical polymerization. During this process, the smaller molecules come together to form cross-linking bonds with each other. These cross-links then turn into tangled three-dimensional networks.

As the oils undergo oxidation, the 3D network grows, and eventually, the paint solidifies. This entire process is also known as the curing of oil paints.

This entire chemical process doesn’t just stop once the paint is dry to the touch. It continues for a long time, sometimes for decades, depending on the thickness of the paint coat. Since the oxygen is absorbed from the surface, the reaction speed in the inner layers is much slower, as compared to the outer ones.

Another fascinating aspect of oil paintings is that in the initial stages of curing, the paintings get heavier from gaining oxygen. In late stages, however, they lose weight as lighter, volatile molecules escape from the dried paint film. This loss of weight contracts the painting and gives rise to the familiar cracks you can see on old oil paintings. Believe it or not, these cracks and the tedious curing process can act as evidence against art frauds and forgeries.

How Does Slow Curing Help Catch A Forger?

As paintings age, they get stiffer due to the nature of the oil used in the paint and only then will start to crack. To the outside world, it might look like a drawback of using oils, but to art historians and forensic experts, it is a necessary evil.

For instance, imagine that an auction house has received a painting that the seller claims is an original piece by Rembrandt, a famous 17th-century artist. Since these period pieces can cost a fortune (tens of millions of dollars), the authorities must make sure that the art is original before it goes for auction.

The first step involves visual inspection, which involves looking for signs of aging, like the Craquelure (a network of cracks). If it’s a forgery, the painting might be devoid of cracks, as freshly painted oils don’t crack easily.

However, forgers have found their way around this. To fake the crackling effect, they often let the painting sit in the sun or bake it for a while to stiffen the paint. Once it is hard enough, they roll a ball over the dried painting or roll it over a cylinder to generate cracks.

The experts soon figured this trick out too, and started looking for fine dust lines. When a painting is out in the world, it starts collecting dust, which sometimes finds its way into the craquelure and settles there. This “tell” was also countered by the filling in the cracks with dark ink to create the illusion of old dust. To read more about this fascinating cat and mouse game, click here.

However, forensic scientists can still beat them in their game by using microscopy. To the naked eye, the fine craquelure might look one-dimensional, but under a microscope, with high magnifying power, they can look like cracks across drought-ridden land. Therefore, using a microscope can help experts determine if there is actual dust, or if it is just filled in with ink.

Another powerful detection tool is X-ray photography, which allows experts to look through different layers of paint. This helps them determine if the cracks are limited to the top layer, which would mean they are relatively new. If the cracks run deep through all layers of paint, this indicates a genuinely old painting.

Conclusion

Next time someone complains about their oil painting not drying fast enough, sit them down and explain the chemistry behind it, and the benefits of the medium.

Now, before we leave here’s the painting that started it all…

References (click to expand)

- Paints - www.sas.upenn.edu

- PAINT MANUFACTURE AND PAINTING - IARC Publications. The International Agency for Research on Cancer

- (2005) Long-Term Chemical and Physical Processes in Oil Paint Films. JSTOR

- (2013) Oil Paints: The Chemistry of Drying Oils and the Potential for .... The Smithsonian Institution

- Theory of crack networks helps understand paint ageing. Chemistry World

- Taft, W. S., Jr., & Mayer, J. W. (2000). Detection of Fakes. The Science of Paintings. Springer New York.

- Craddock P. T. (2009). Scientific Investigation of Copies, Fakes and Forgeries. Routledge