Table of Contents (click to expand)

Freezing or attentive immobility is the ‘fight-or-flight response put on hold’. During freezing, both the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems get activated simultaneously. In the brain, certain regions linked to motor control are activated, which leads to physically freezing in place.

If you’re anything like me, you probably hate the idea of public speaking. You prepare like crazy for a speech and practice giving it in front of a mirror a million times. You imagine yourself in front of the crowd, testing it out on family and friends. You’ve practiced so much that you essentially have the speech memorized.

However, when the time finally comes, you freeze.

The fight-or-flight response can enable you to survive terrifying situations—leaping away to avoid an oncoming car or defending yourself when someone pulls a knife on you can determine your survivability.

Even so, many of us end up like a deer caught in the headlights—frozen and unable to move. Why do we do this? Especially when freezing can make things so much worse, like stopping in front of a moving car.

What happens inside our body that causes this freezing response?

Recommended Video for you:

Why Do We Freeze?

In the preposterous event that you’re lost in a forest and come in close proximity to a tiger (or a lion, or a wolf, or a raging elephant, depending on your GPS coordinates), certain regions of your brain will activate to either fight, flee or freeze in response. Apart from these three well-known responses, your body can also experience tonic immobility or collapsed immobility when fighting or fleeing is simply not possible.

In the scientific community, freezing is called ‘attentive immobility’ and is often considered an intermediary step between stressful stimuli and taking action, such as fighting or fleeing. The word ‘attentive immobility’ tells you what it is. When you freeze, everything seems to be happening in slow motion because you pay careful attention to things happening around you.

Animals sometimes freeze to help escape detection and scan the environment when they feel threatened by a predator.

Another response is tonic immobility. Unlike freezing, which happens early on during stressful situations, tonic immobility occurs much later, when you do not have the option to escape. Attentive immobility actively prepares you to face your fear.

Tonic immobility, on the other hand, helps animals play dead to avoid being eaten, as predators often do not consume dead things. While this won’t work against a scavenging vulture, it might deter a bear from hunting you down. If you have heard of opossums suddenly going still and playing dead, then you know what I’m talking about.

It might seem like freezing is the opposite of what you want to do when faced with a threat, but it can actually save your life in certain situations.

Let’s say you’re a cop tasked with busting a drug cartel. You and your squad are inside an abandoned building, in an active shooting zone. You’re hiding behind a slab of concrete when suddenly a man appears in front of you with a gun. You freeze for a few seconds, your gun aimed at the man, before you realize that he’s actually a member of your squad.

Since this phenomenon typically only lasts for a few seconds, your heightened attention during freezing might let you process what you see before you start attacking. In that situation, you would probably breathe a sigh of relief knowing that you hadn’t shot someone on your side.

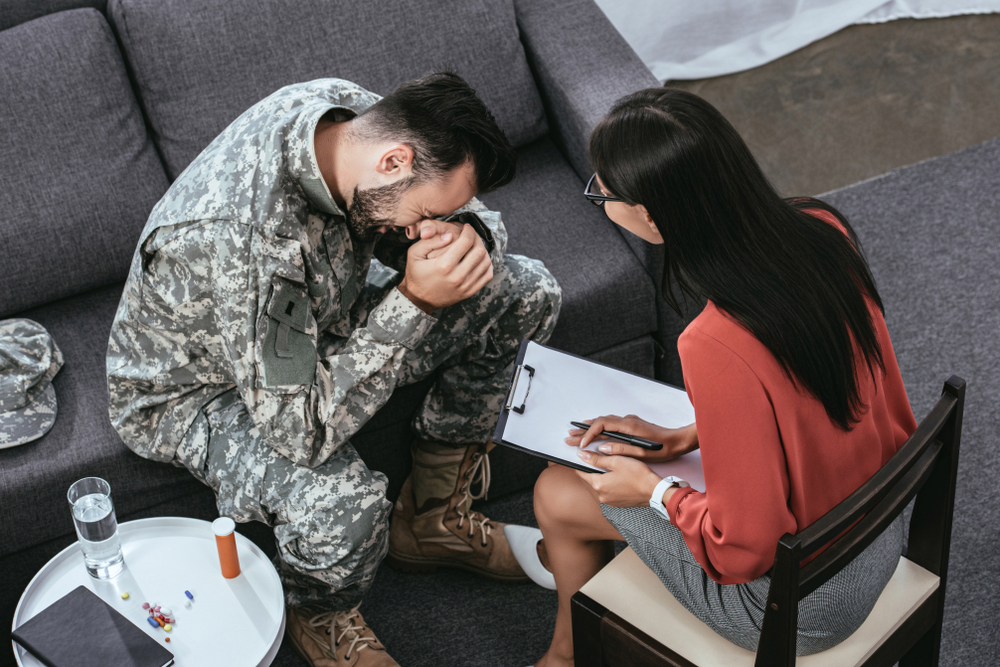

However, more often than not, freezing becomes a hindrance in our day-to-day lives. People with anxiety disorders have a hard time managing their freezing response. People with post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD (often seen in people with traumatic memories) experience freezing behavior long after the threat has passed.

Sachin Patel, a general psychiatry director at Vanderbilt, said to VUMC reporter, “It’s like they’re [people with PTSD] stuck on the freezing channel and can’t flip back to the […] normal behavior channel,”

Research is still ongoing on how we can tackle the improper timing of this response. However, in order to do so, we must first understand what’s going on inside our body when this inactivity occurs.

What Happens In The Body When We Freeze?

The autonomic nervous system plays a huge role in producing defensive physiological and behavioral responses to a threat. This system broadly consists of two parts—the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems.

You might have heard about these systems in relation to the fight-or-flight response. That is because the sympathetic system provides you with the energy to tackle the perceived threat by activating that fight-or-flight response. The parasympathetic system, on the other hand, makes sure you can rest and recover after the danger has passed.

You can learn more about the body’s fight-or-flight response in another article on this website.

Freezing, or attentive immobility, is ‘fight-or-flight response put on hold’. While freezing, both the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems are activated simultaneously.

As a result of the activation of the sympathetic system, there is increased pain tolerance, respiration, and muscle contraction (you feel very tense). However, the parasympathetic system usually dominates the body during a freezing response, which is why your heart rate decreases.

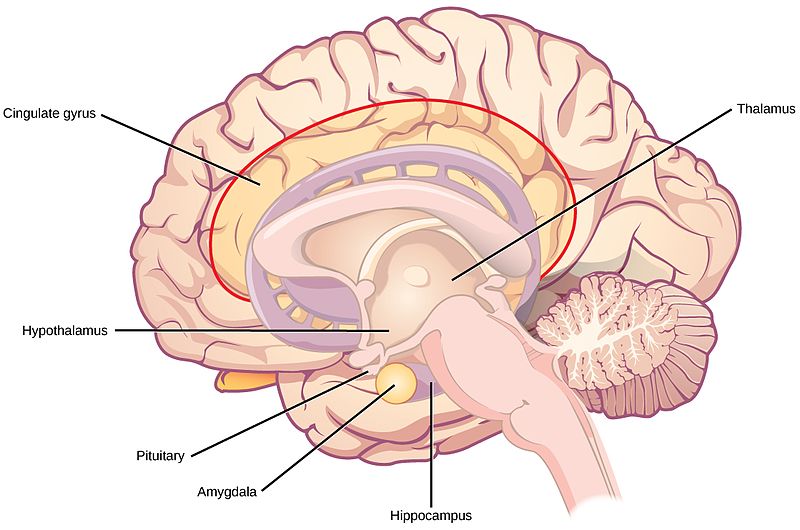

Inside the brain, frightening stimuli activate the amygdala. This, in turn, will stimulate the hypothalamus to generate a sympathetic response, and stimulate the medullar nuclei for a parasympathetic response.

That’s not all! If you recall, freezing puts a temporary halt on the fight-or-flight response, but how does that happen?

Apart from the aforementioned connections, the amygdala is also linked with another structure called the ventrolateral periaqueductal grey (vlPAG) in the brain. During freezing, vlPAG activation inhibits the activity of lateral PAG, which is involved during the fight-or-flight response. Since lateral PAG is responsible for motor activity, you become immobile when this region becomes inhibited and you freeze.

Thankfully, this phase is temporary. Although you can’t move, your muscle tone is increased. This allows you to spring into action the moment you unfreeze.

If you want to have an in-depth understanding of this interesting phenomenon, you should read an excellent review article about the mechanisms underlying freezing, as published in Philosophical Transactions of Royal Society B.

A Final Word

As with many aspects of biology and behavior, we are continually discovering new things all the time. The data shows that it’s time to update our vocabulary from “fight or flight” to the 3 F’s; fight, flight or freeze. Sometimes this pattern is useful to avoid detection by hungry predators, and other times it ends with the deer in the headlights becoming roadkill. Whatever the outcome, the more we learn about how our brain responds to stress, the better off we’ll be. Keep learning and always look both ways before crossing the road!

References (click to expand)

- Roelofs, K. (2017, February 27). Freeze for action: neurobiological mechanisms in animal and human freezing. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. The Royal Society.

- Kozlowska, K., Walker, P., McLean, L., & Carrive, P. (2015, July). Fear and the Defense Cascade. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health).

- Riskind, J. H., Sagliano, L., Trojano, L., & Conson, M. (2016, April 19). Dysfunctional Freezing Responses to Approaching Stimuli in Persons with a Looming Cognitive Style for Physical Threats. Frontiers in Psychology. Frontiers Media SA.

- Study finds 'frozen' fear response may underlie PTSD. The Vanderbilt University Medical Center

- Understanding the stress response - Harvard Health. Harvard University