Table of Contents (click to expand)

The body doesn’t have an inherent preference for healing one body part over another, but some parts of the body, by virtue of their design and function, heal faster than others.

If you are someone who does a job that makes you prone to injuries or perhaps you’re just a bit clumsy, then you have probably observed that wounds in some parts of the body heal faster than others.

But why is that? Is the body biased when it comes to treating injuries?

Recommended Video for you:

How Does A Wound Heal?

To begin with, we’ll talk about wounds that happen to the skin, or close to it.

The moment we cut our finger with a knife or take a fall from a bicycle and scratch our elbow, we run to clean the wound and apply a bandage. However, under the bandage, a cascade of chemical processes is occurring and an army of blood cells are working overtime to heal the wound. Before taking a dive into how blood performs this miraculous healing, click here to brush up on your knowledge of blood and its components.

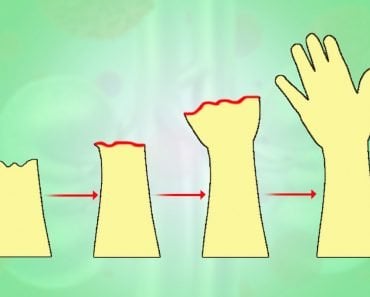

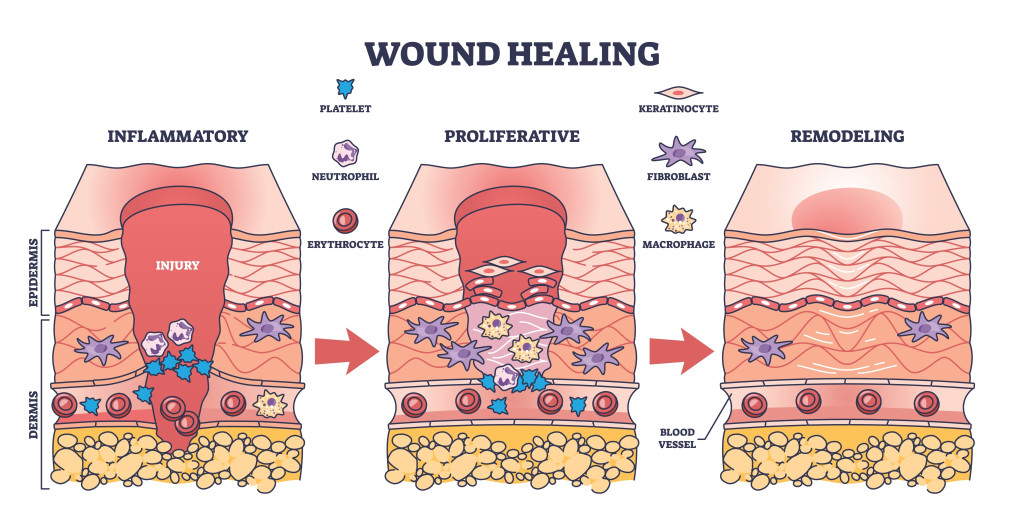

Wound healing is a complex four-phase process.

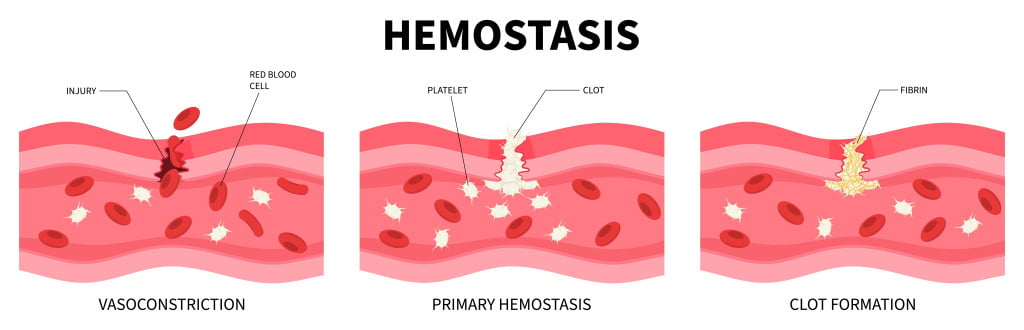

Hemostasis

The first step is to stop the bleeding. When bleeding occurs, the blood vessels constrict, which temporarily reduces or stops the flow of blood to the wounded site. Vasoconstriction will only stop the bleeding until a lack of oxygen near the wound once again causes the blood vessel to relax. This will ultimately restart the bleeding from the site of injury. In other words, reducing blood flow to the area isn’t enough.

To counter this, long thread-like proteins called fibrin threads form a mesh, which we call a clot, to plug the rupture in the blood vessel. This is why we eventually stop bleeding.

Inflammation

Once the bleeding is under control, your immune system’s white blood cells, such as neutrophils, macrophages and lymphocytes, arrive at the scene.

The neutrophils destroy and remove invading microbes and damaged tissues through a process called phagocytosis. 48-72 hours after injury, macrophages enter the scene and continue phagocytosis, while stimulating other cells of the immune system. The function of T-cells (a kind of lymphocyte) isn’t completely understood, but having a low T-cell count is associated with impaired wound healing.

Proliferation

This step starts 3 days after the injury and lasts for the next two weeks. At this stage, the body is repairing the damage done to the tissue. All the damaged cells, such as the cells that make up the skin, begin to divide to create new skin. The margins of the wound start contracting and new blood vessels form.

Tissue Remodeling

This is the final stage of wound healing. During this phase, a new epithelium layer develops, along with the formation of scar tissue. The collagen fibers of the skin reorganize to build the skin’s strength. As the injury begins to heal, the metabolic activity and blood flow in the area decrease. The previously wounded area is now left with a matured scar with decreased cell numbers.

Parts Of The Skin Heal Quicker Than Others

Which skin wounds heal faster than others will depend on a few things.

First, how much blood flow does that part of the skin receive? Blood carries essential nutrients and oxygen, along with the army of blood cells that are crucial to the healing process.

Second, how moist is that part of the skin? There is evidence that moisture makes a wound heal faster than if the conditions around the wound are dry.

Third, does that part of the body have natural anti-microbial chemicals?

Considering all this, if we had to order parts of the body based on how fast they heal, the mouth would come out on top. Compared to scrapes on any other part of the skin, wounds in the mouth heal notably faster.

The mouth’s skin is highly vascularized and has proteins only found on the mouth’s surface. Our saliva contains proteins called secretory leukocyte protease inhibitors (SLPI) and Trefoil Factor 3 (TFF3), which both enhance the wound healing process. Additionally, the saliva contains histatins (a histidine-rich antimicrobial peptide) that stimulate the movement of epithelial cells and fibroblasts to aid in rapid wound closure.

The saliva also creates a humid environment that helps the inflammatory cells in wound healing. The unique environment of the oral cavity explains why injuries in the mouth heal faster with less scarring.

Despite housing millions of bacteria, wounds inside the mouth are also able to stay remarkably clear of any infections.

Factors That Affect Wound Healing

The ability of the body to heal wounds differs from person to person. However, there are certain factors that affect wound healing (both internal and external) and they can be classified into two groups: local and systemic factors.

Local Factors

Local factors are those that have a direct effect on the nature of the wound, thereby influencing the way the wound heals. These include factors like oxygen saturation, blood circulation, wound infection, hygiene of the infected site, etc.

The body requires energy to heal wounds. Oxygen is a crucial part of energy production by mitochondria in cells that use ATP molecules. Oxygen also prevents infections near the wound site and increases re-epithelialization, collagen synthesis, etc. Thus, prolonged hypoxia (absence of oxygen) can impair wound healing.

An open wound is bound to see a rise in bacterial colonization, but not all bacteria are bad. Some can even help in the wound healing process, while others can form a protective biofilm over the wound that is resistant to conventional antibiotic treatment. Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) are common bacteria that infect wounds. Such infected wounds are difficult to treat and do not heal unless the biofilm is shed.

Systemic Factor

Systemic factors include factors like the overall health of the individual that can indirectly affect the nature of wound healing. Age, sex hormones, stress, diseases like diabetes and fibrosis, nutrition, obesity, and alcoholism are some systemic factors.

Older individuals show delayed collagen synthesis and the T-cells take a longer time to arrive at the wounded site, which makes healing a slower process. Additionally, older folks are prone to injuries like cuts and tears, as their skin is thinner and loses its elasticity with age.

High blood sugar levels can constrict the blood vessels, which in turn reduces the blood supply to the wounded site. As discussed earlier, a healthy supply of blood to any wound is crucial for the healing process.

Other than these considerations, there are other factors, such as the use of medications that can alter the chemistry of the body, smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, and poor diet, all of which can negatively impact the healing process of the body.

Conclusion

Survival is the driving focus of all the mechanisms of the body and wound healing is one of the most crucial aspects of survival. The rate at which a wound heals depends on how rich the supply of blood is to that region. Apart from that, certain factors like age, genetics, the presence of bacterial infection, pre-existing diseases and other lifestyle choices can negatively impact how the body responds to a wound.

References (click to expand)

- Brand, H. S., & Veerman, E. C. (2013). Saliva and wound healing. The Chinese journal of dental research : the official journal of the Scientific Section of the Chinese Stomatological Association (CSA), 16(1), 7–12.

- Velnar, T., Bailey, T., & Smrkolj, V. (2009, October). The Wound Healing Process: An Overview of the Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms. Journal of International Medical Research. SAGE Publications.

- Guo, S., & DiPietro, L. A. (2010, February 5). Factors Affecting Wound Healing. Journal of Dental Research. SAGE Publications.

- Brand, H. S., Ligtenberg, A. J. M., & Veerman, E. C. I. (2014). Saliva and Wound Healing. Monographs in Oral Science. S. Karger AG.