Table of Contents (click to expand)

Our native language can shape our non-linguistic abilities that often seem extremely objective, such as color perception. Our thinking is constrained by the language we speak.

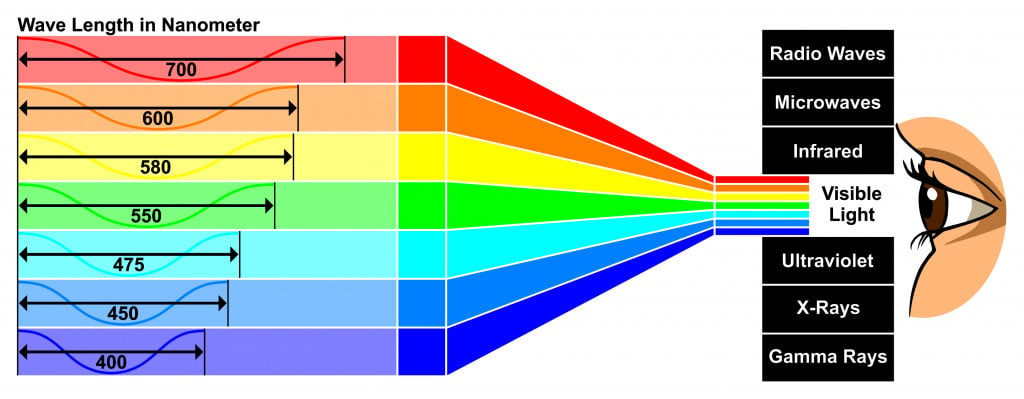

The rainbow contains all the colors of the world in a continuous spectrum. There are an infinite number of colors, yet we are able to distinguish between even mild differences in hues with our eyes.

Even so, we don’t have names for every color; instead, we group colors into categories and name the categories.

For example, we teach children only a few color labels or categories, such as the seven in the rainbow – VIBGYOR (Violet, Indigo, Blue, Green, Yellow, Orange, Red). These are the commonly used categories in English. Colors that fall between these categories are grouped into whichever color category it is nearest.

These color names vary in different languages. Some languages have categories that do not exist in others, so how does this affect their color discrimination? Furthermore, does the perception of color vary based on the languages we speak?

Recommended Video for you:

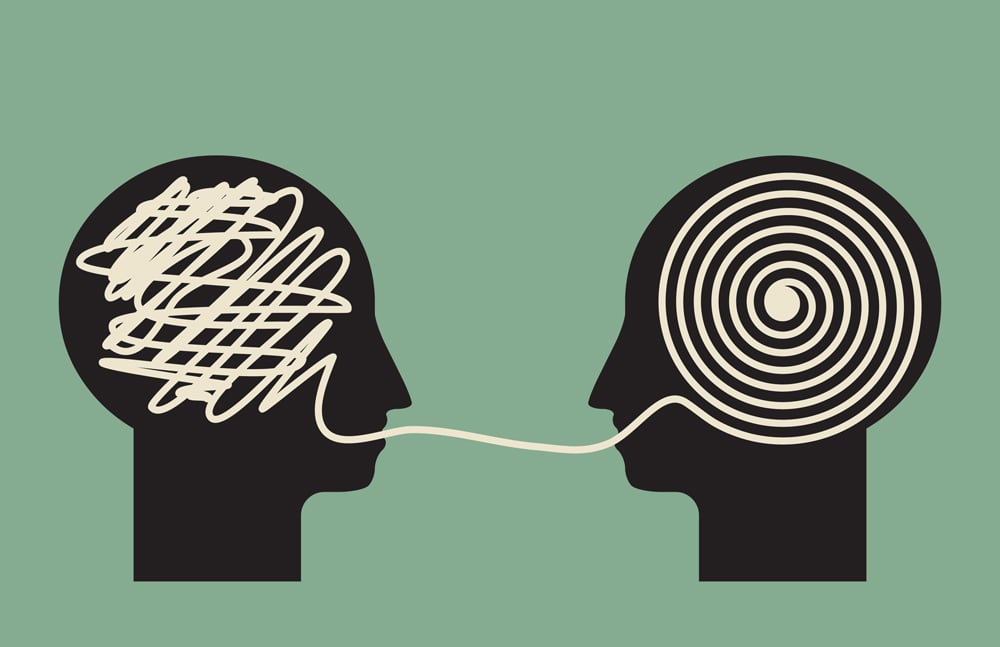

Whorfian Hypothesis

The idea that the language we speak can influence thought to some extent is called the Whorfian hypothesis of linguistic relativity. This is a theory in psychology positing that language can influence cognition or thought, suggesting that speakers of different languages think differently.

Scientists who investigate this theory are interested in investigating how language can alter our perception and thought. Some of them use color perception or discrimination as a window into understanding how language shapes our thought. This is because color perception provides a neat example where the categories we make will vary between languages.

Color Names Vary Based On Language

Color names are not universal. In English, we commonly use about 11 color names to describe colors around us. However, this number varies based on language. The Pirahã language, spoken by Tribes that live in the Amazon, uses only two categories—dark and light—and have no color names!

Some other languages have categories that don’t exist in English. For example, the Korean language has a category or label for the blue-green color (Cheongnok) in addition to blue (Parang) and green (Chorok) labels. The Russian language has separate color names for light (Goluboy) and dark blue (Siniy).

This diversity in color naming is why color perception is a convenient process to study in order to understand whether language affects perception.

The ‘Russian Blues’ Experiment

Shades of blue form a continuous category for English speakers. We use the term ‘blue’ to define all colors in that spectrum. We distinguish colors within it using terms such as ‘dark/light’. However, the Russian language doesn’t have a single word for ‘blue’. As mentioned before, they use entirely separate terms for light blue and dark blue.

Scientists exploited this difference in languages in an experiment on color discrimination in English and Russian speakers. In this experiment, they made Russian and English speakers perform a color discrimination task using three squares of blue color. The participants were presented with three blue squares, with one square on top and two at the bottom. They were asked which of the bottom squares matched the color of the top square.

Here’s the catch! In some trials of the experiment, one of the bottom squares was light blue, in some both were light blue, and in others both were dark blue. To an English speaker, this wouldn’t make any difference, because they’re all just shades of ‘blue’. But to a Russian speaker, some trials required distinction between a Siniy and Goluboy, whereas others required distinguishing between two Siniys or two Goluboys.

Not surprisingly, results of the experiment showed that Russian speakers were faster in discriminating colors when they fell in two different categories (siniys and goluboys) than when they were in the same category (both siniy or both goluboy). Distinguishing colors that fell in the same category (both siniy or both goluboy) was arguably more difficult and time-consuming for them. On the other hand, no such effect was found in English speakers, as all tasks were equal to them – the task of discriminating between ‘blues’.

Although the task did not require the participants to use any language, it clearly reflected their ability to discriminate colors! The Russians used a language that consistently made them draw a boundary between dark and light blue shades, which made them faster in discriminating these categories. English speakers don’t habitually make this distinction in their everyday life, so they showed no such effects in color discrimination.

This provided evidence for the Whorfian hypothesis that language can influence non-linguistic abilities, and therefore, people who speak different languages can perceive things differently. Language can interfere even in perceptual processes that are ordinarily thought to be ‘objective’, such as color perception.

Several other studies reported similar findings, such as Korean speakers showing an advantage in perceiving the blue-green category unique to their language. Later studies in Greek speakers who have light and dark blue categories (Ghalazio and Ble), like in Russian, showed that this advantage in color discrimination arises from brain processes at the unconscious level.

Ending Note

We often think of language as a small domain of our cognitive ability, but psychologists have long believed that language has the ability to affect many non-linguistic abilities, since it influences our thought. Experiments testing this hypothesis using color perception as an example suggest that our perception is indeed shaped by our language!

In addition to these revelations, scientists have shown that language can affect a wide range of our abilities, including our spatial analogies, perception of motion, numbers, our understanding of false beliefs, object categories, perception of gender, etc.

For example, the word apple is assigned the masculine gender in German, but it is feminine in Spanish. Studies showed that German speakers find it easier to memorize male names (e.g., Patrick) with the word ‘apple’, whereas Spanish speakers find it easier to remember the word apple alongside female names (e.g., Patricia). Such examples of language influencing thought are endless!

The take-home message here is that our native language can shape even our non-linguistic abilities that often seem extremely objective (such as color perception). Our thinking is constrained and cleverly shaped by the language we speak!

References (click to expand)

- Hunt, E., & Agnoli, F. (1991, July). The Whorfian hypothesis: A cognitive psychology perspective. Psychological Review. American Psychological Association (APA).

- Winawer, J., Witthoft, N., Frank, M. C., Wu, L., Wade, A. R., & Boroditsky, L. (2007, May 8). Russian blues reveal effects of language on color discrimination. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- Roberson, D., & Hanley, J. R. (2007, August). Color Vision: Color Categories Vary with Language after All. Current Biology. Elsevier BV.

- Thierry, G., Athanasopoulos, P., Wiggett, A., Dering, B., & Kuipers, J.-R. (2009, March 17). Unconscious effects of language-specific terminology on preattentive color perception. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- Wolff, P., & Holmes, K. J. (2010, October 27). Linguistic relativity. WIREs Cognitive Science. Wiley.

- Language in Mind - MIT Press. The MIT Press