Table of Contents (click to expand)

Hypothetically speaking, since both our eyes share the same anatomy and nerve structures, it would hardly matter whether a transplanted eye belongs to the right socket or the left one. So far, complete eye transplantation has been impossible, but research suggests that transplanting the whole eye may be possible in the future.

Transplantation is a surgical procedure in which damaged cells, tissues, or organs are removed and replaced by healthy ones, either from another donor or from another part of the body. Over the past few centuries, it has developed into a groundbreaking field of modern medicine. Transplants can be used as treatments for various medical conditions, from life-threatening organ failures to blurred vision.

Recommended Video for you:

How Do Current Eye Transplants Work?

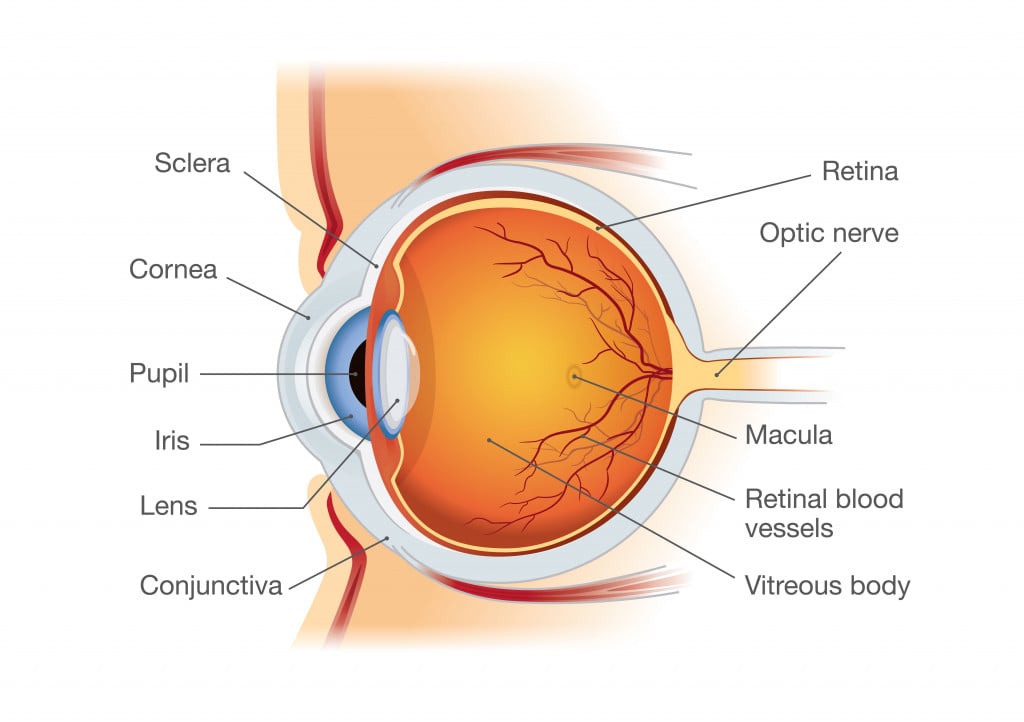

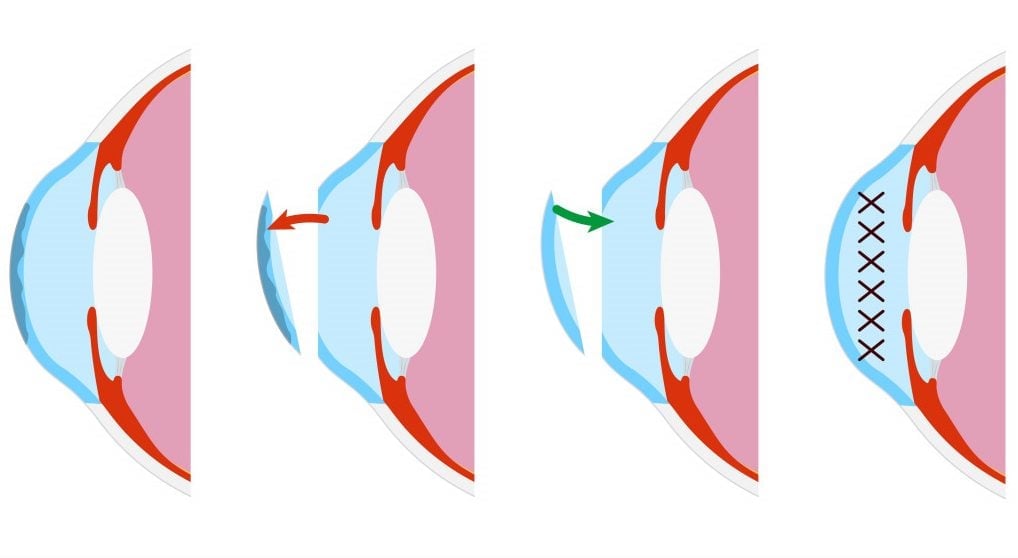

When one talks about eye transplants, they’re usually referring to transplanting a cornea: the transparent layer of tissues covering the front of our eye. It helps to focus light in the eye, and acts as a protective covering. Transplanting it can be a treatment for damaged eyes, pain, cases of blurred vision due to weakened, thin or swollen corneas, and corneal infection or injury. It is referred to as keratoplasty.

Franz Reisinger suggested transplanting animal corneas in human eyes, but his experiments on rabbits and chickens were met with disappointment. A breakthrough was made by surgeon Samuel Bigger, who performed keratoplasty on a pet gazelle with a scarred cornea in 1837. The cornea was taken from another wounded gazelle. Within ten days, complete vision restoration was observed in the animal.

The first successful corneal transplant in humans was then performed in 1905 by Eduard Zirm, on a 45-year old farm laborer who had suffered from burns. The donor was a blind eleven-year-old with functional corneal tissue.

The technique used by E. Zirm has served as an outline that has been refined by several scientists over the last century.

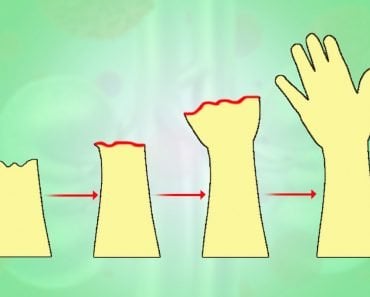

Corneal transplants can be of various types, depending on the seriousness of one’s condition. When both the outer and inner layers of the cornea are damaged, the entire cornea is replaced, referred to as a penetrating keratoplasty. If either the outer or the inner layer is damaged and the rest of the cornea is intact, a partial keratoplasty can replace the affected layers.

Research for future developments in keratoplasty includes a bioengineered cornea that can reduce most of the current limitations associated with the surgery.

Corneal eye transplants, however, aren’t sufficient to restore vision loss caused by a weakened optic nerve or cell loss in the retina (the layer at the back of one’s eye that is sensitive to light).

This is where whole-eye transplantation comes into the picture.

Can The Left Eye Be Transplanted Into The Right Socket?

Hypothetically speaking, since both our eyes share the same anatomy and nerve structures, it would hardly matter whether a transplanted eye belonged to the right socket or the left one.

Why are we only speaking hypothetically?

Even though a great deal of research has been conducted in the field of transplants, medical experts have not yet been able to successfully transplant an entire eye from one donor to another.

Our eyes are connected to the brain via optic nerves, which transfer visual cues between the eye and the brain. An optic nerve consists of around one million nerve fibers. Reconnecting these in a replanted eye isn’t feasible. Connecting the numerous blood vessels associated with the eye is a tedious task as well, though not as difficult as the successful regeneration of nerve fibers.

History And Future Of Whole-eye Transplantation

The first mammalian whole-eye transplantation was performed in 1885 in rabbits, and no vision restoration was observed in the test subjects. The first human eye transplant involved placing a rabbit eye in the eye sac of a 17-year-old. This was also unsuccessful. Later that year, attempts to connect transplanted optic nerves were made, one of which, executed by Bradford, lasted for eighteen days before the eye began to die.

We have come a long way since then.

Mammalian eyes, specifically those of rats, bear a striking anatomical similarity to humans, which makes them an ideal test subject for transplants.

Researchers have conducted studies investigating how blood vessels reconnect in the transplanted eyes. They discovered active blood circulation in all subjects from blood vessels in the extraocular muscles. Blood circulation is an important point to consider, as poor circulation might limit one’s vision.

Since behavioral responses to light were also recognized in a few of the rodents, hinting towards partial vision, the research holds great promise.

The current challenges include the development of improved nerve regeneration capabilities, so that the eye can transmit signals to the brain after transplantation. Scientists have, however, identified proteins in the optic nerve that are involved in the growth, survival and maintenance of developing neurons, which can help grow and connect nerve fibers without complications in the future.

Immunology advancements may reduce the rejection of the newly transplanted eye by the recipient’s body, which is a problem across all kinds of transplants, as the human body tends to reject tissue that it doesn’t identify as its own.

What does the future of eye-transplantation hold?

Funded by the U.S. Department of Defense, teams of transplant surgeons and researchers at the University of California and Pittsburgh Medical Center aim to achieve the same level of prowess within the decade. Looking forward, we might not have long to wait before the first success story of whole-eye transplants.

References (click to expand)

- Bigger, S. L. L. (1837, July). An inquiry into the possibility of transplanting the cornea, with the view of relieving blindness (hitherto deemed incurable) caused by several diseases of that structure. The Dublin Journal of Medical Science. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Armitage, W. J. (2006, July 26). The first successful full-thickness corneal transplant: a commentary on Eduard Zirm's landmark paper of 1906. British Journal of Ophthalmology. BMJ.

- Griffith, M., Osborne, R., Munger, R., Xiong, X., Doillon, C. J., Laycock, N. L. C., … Watsky, M. A. (1999, December 10). Functional Human Corneal Equivalents Constructed from Cell Lines. Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

- Badaro, E., Cassini, P., Andrade, G. C. de ., Rodrigues, G. B., Novais, E. A., & Rodrigues, E. B. (2022). Preliminary study of rabbits as an animal model of mammalian eye transplantation and literature review. Revista Brasileira de Oftalmologia. Revista Brasileira de Oftalmologia.

- Hotz, F. C. (1888, July 14). The Transplanting Of A Rabbit'S Cornea Into The Human Eye. Journal of the American Medical Association. American Medical Association (AMA).

- Freed, W. J., & Jed Wyatt, R. (1980, August). Transplantation of eyes to the adult rat brain: Histological findings and light-evoked potential response. Life Sciences. Elsevier BV.

- Benowitz, L. I. (2010, August 1). Optic Nerve Regeneration. Archives of Ophthalmology. American Medical Association (AMA).

- Looking Ahead: Whole Eye Transplant Under Development. The University of California, San Diego