Table of Contents (click to expand)

We don’t know exactly when animals first started feeling pain, but we do know that it is a very old evolutionary response. Nociceptors, special pain receptors, are found in all animals, from humans to fish to birds to amphibians. These receptors are responsible for the different types of pain that we feel, from fast, immediate pain to slow, dull pain. Scientists are still studying how pain works in different animals, but we do know that it is a complex process that involves several parts of the brain.

https://www.neuroscience.cam.ac.uk/publications/download.php?id=31984Without the ability to feel pain, no one would know that they’ve been burned, or scratched, or are suffering from a heart attack. Pain is the alarm that tells us that there is something wrong that must be fixed. That being said, when did animals first start feeling pain?

Recommended Video for you:

How Do We Feel Pain?

Before we deep dive into the question of where pain originated, let’s take a look at how humans feel pain.

Nociceptors

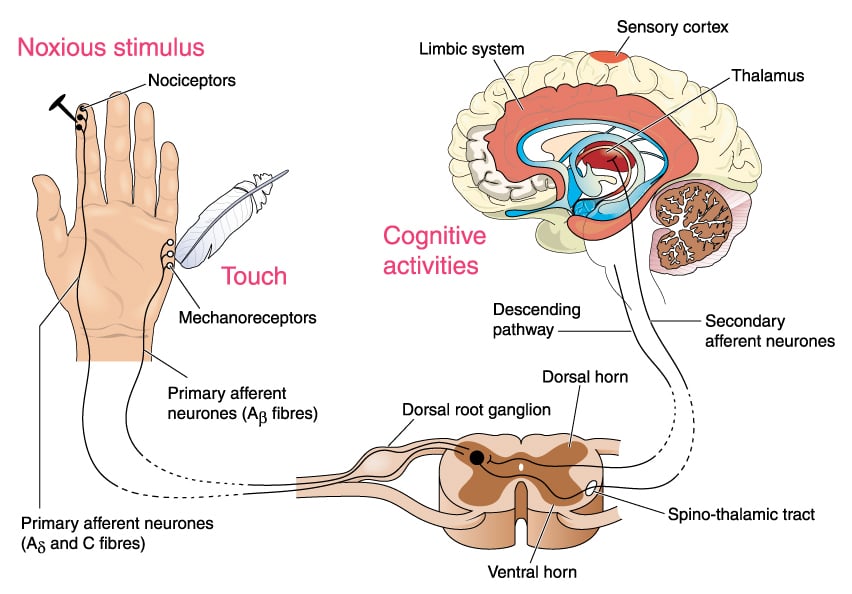

Pain is felt due to the presence of special pain receptors called nociceptors. There are different subtypes of nociceptors that respond to different pain stimuli, which are categorized as mechanical, thermal and chemical.

Types Of Pain

All pain is not the same. There is fast, immediate pain, as well as slow and dull pain. These two types of pain are caused by different neurons—the Aδ group and C group, respectively.

The Aδ group are myelinated (neurons that have a myelin sheath around its axon) and are responsible for the immediate intensity with which pain is felt. The C fibers are unmyelinated (neurons that do not have a myelin sheath around their axon) and transmit the signal of pain much slower and at a decreased intensity, which is why we feel a slow dull throbbing.

These neurons carry the signal to the brain through various pain pathways, which is then finally felt as pain. The immediate reflex upon feeling pain works similar to a normal reflex. Several parts of the brain are involved in processing pain and there isn’t a single “pain center” in the brain. These pathways are complex, and scientists are still discovering new aspects of pain sensation.

Which Animals Feel Pain?

When discussing pain, humans and mammals come to mind first.

But, pain is a much older evolutionary response and has been conserved (has not changed much over time). Various animals share the same type of molecules and neurons dedicated to pain and pain processing. However, other members of the animal kingdom, such as birds, amphibians and fish, most likely feel pain as well.

To say with absolute certainty that animals other than humans feel pain is tricky. Most animals cannot tell a researcher, “I’m feeling pain”, in the same way a human does. A great deal of research relies on this ability to directly communicate or other behaviors that clearly mark pain.

Scientists have found a way around that. For rats, behavior like flicking the tail, withdrawing the limbs, and self-mutilation have all been used to measure an organism’s response to pain. Other behavioral patterns are being studied in fish, birds and amphibians to determine their response to pain.

Evolutionary Origins Of Pain

According to a paper by Dr Broom of Cambridge University, the most primitive forms of pain began with cells becoming sensitive to harm and then learning how to avoid the stimulus. These cells wouldn’t feel pain the same way we do though. The next step would be to coordinate this response with the behavior of the whole organism, undoubtedly helped by the evolution of the nervous system.

As the nervous system evolved and became more complex in more evolved animals, the manner in which animals felt pain also evolved.

The response to pain, as well as the actions to prevent it, can be modulated depending on the situation. Higher organisms, like humans, can pinpoint where the pain is situated. They can then change their behavior to pain depending on the situation they are in. This is shown to be the case in apes, who keep silent during childbirth, a recorded painful process, but screams could attract predators (Source).

Relying purely on behavior is not sufficient to study pain. Scientists study molecules, cells and pain pathways in the brain to see evolutionary relationships between how pain works in different animals.

Vallinoid receptors are a part of the larger family of Transient Receptor Potential channel of proteins, which are receptors that detect a range of negative or undesirable stimuli. These receptors are being used by scientists to study pain and aversion on a molecular level, from humans to a 1mm long nematode, C. elegans.

TRPV1 is a receptor that detects noxious thermal stimuli. Interestingly, it is this same receptor that binds to capsaicin, a chemical in chili peppers, which makes one feel “hot” and “burning” sensations upon eating that intense food. Studying the function, role and structure of these receptors in animals other than humans reveals a part of the puzzle of how pain evolved and is experienced.

It is difficult to say which animal was the first to develop pain. Learned aversion to harmful stimuli has been seen in mollusks, whose nervous system is far more primitive than vertebrates. Another question being researched is whether learning to avoid something dangerous involves pain. Just because an organism shows a learned aversion, does that mean it experiences pain? These questions require additional research and the study of molecular mechanisms regarding how pain is felt.

References (click to expand)

- anterior cingulate cortex - The Brain. McGill University

- 484 Broom Evolution of Pain - Cambridge Neuroscience. neuroscience.cam.ac.uk

- Kadowaki, T. (2015, April 1). Evolutionary dynamics of metazoan TRP channels. Pflügers Archiv - European Journal of Physiology. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Purves D., Augustine G., Fitzpatrick D., Hall W. C., Lamantia A., Mooney R.,& White L. E. (2018). Neuroscience. Sinauer