Table of Contents (click to expand)

Motion sickness patches contain scopolamine, a plant-based alkaloid, which inhibits the vomiting response of the brain. It works by inhibiting neurons involved in the vomiting response that employ a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine.

Have you ever felt nauseous while riding in a car and simultaneously trying to read a book or scroll through your phone? Or perhaps you’ve gone “green” while on a boat or ship? Or what about a rollercoaster ride? That intense feeling of nausea you experience when you are on moving objects like cars, ships, or rollercoasters is commonly called “motion sickness”.

The discomfort goes by different names, such as car-sickness or sea-sickness, but the symptoms remain the same across all modes of transport.

The word ‘nausea’ itself owes its origins to motion sickness! It was derived from the Greek word ‘naus’ meaning ship, to denote the sickness felt during sailing on a ship. Historically, ancient Greeks, Romans, and Chinese historians and academics recorded several accounts of seasickness in their classics.

Motion sickness had caused considerable distress to Napoleon and his ‘camel corps’ – a military squadron that used camels for transport, during his campaign in Egypt (camel sickness to be exact!). In modern times, astronauts experience a form of ‘space motion sickness’ in spacecraft.

It is a problem that humans have faced across time while using various forms of transport.

Fortunately, with developments in science, we have been able to come up with a brilliant solution to this problem—motion sickness patches.

Stick one of these patches behind your ear and Voila! You’re good to go on that long drive or boat trip, without your innards churning! So what is the magic behind this simple remedy?

Recommended Video for you:

Behind The Scenes Of Motion Sickness

In simple terms, motion sickness is a syndrome caused by real or perceived motion that leads to a person experiencing nausea, vomiting, cold sweats, and other unpleasant symptoms, but why does something as harmless as movement cause sickness?

When you’re riding in a car and looking at a stationary object, like a book or a phone, your eyes report to the brain that you are ‘not moving’.

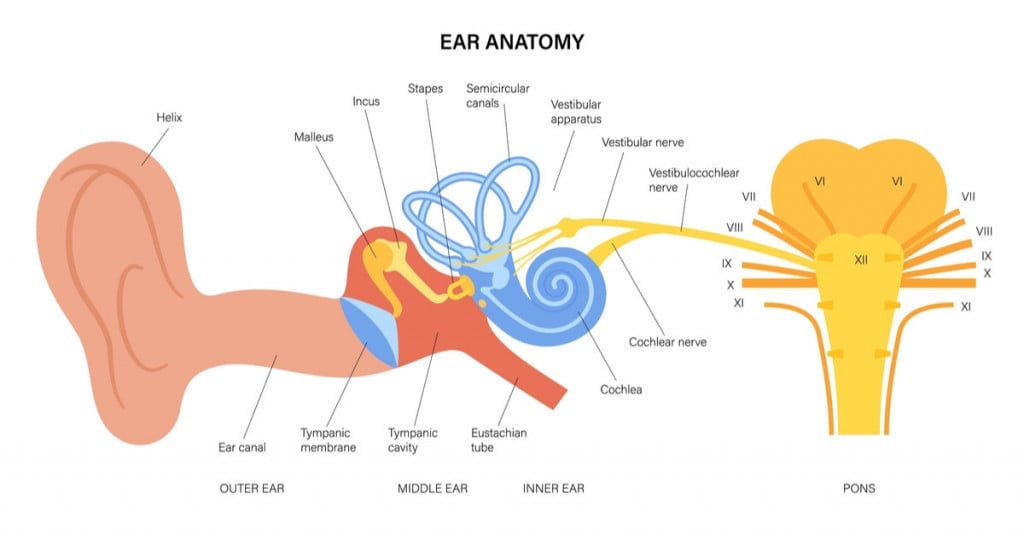

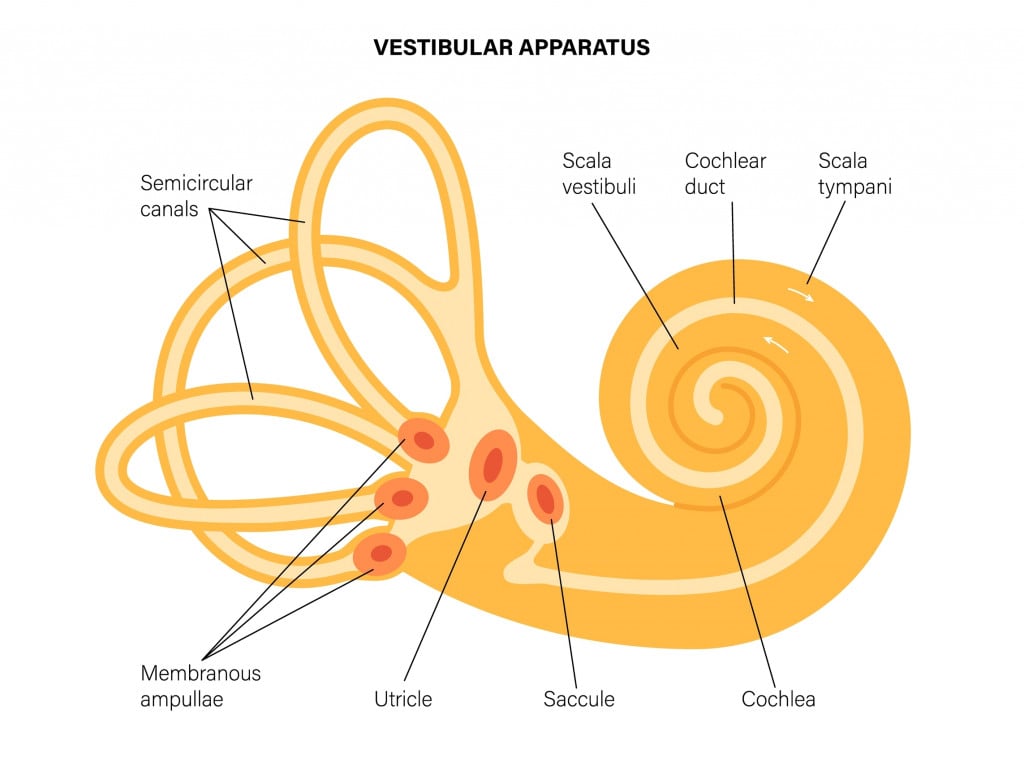

At the same time, the vestibular system in your inner ear, which takes care of balance, reports a completely different story to your brain.

Inner ear structures called semicircular canals detect rotational motion, whereas the utricle and saccule detect linear motion. These structures detect the movement of the car from your head movement and report to the brain that you are ‘moving’.

Your brain thus receives conflicting information from the inner ear, the eyes, and your other senses.

As a result, it concludes that your sense organs are going whack after ingesting a toxic substance. This is because, in a natural setting, that’s the only scenario that can cause such mismatched reports from the senses.

The real cause—transportation—is a recent human invention, and an artificial setting that the brain is not evolutionarily built to handle.

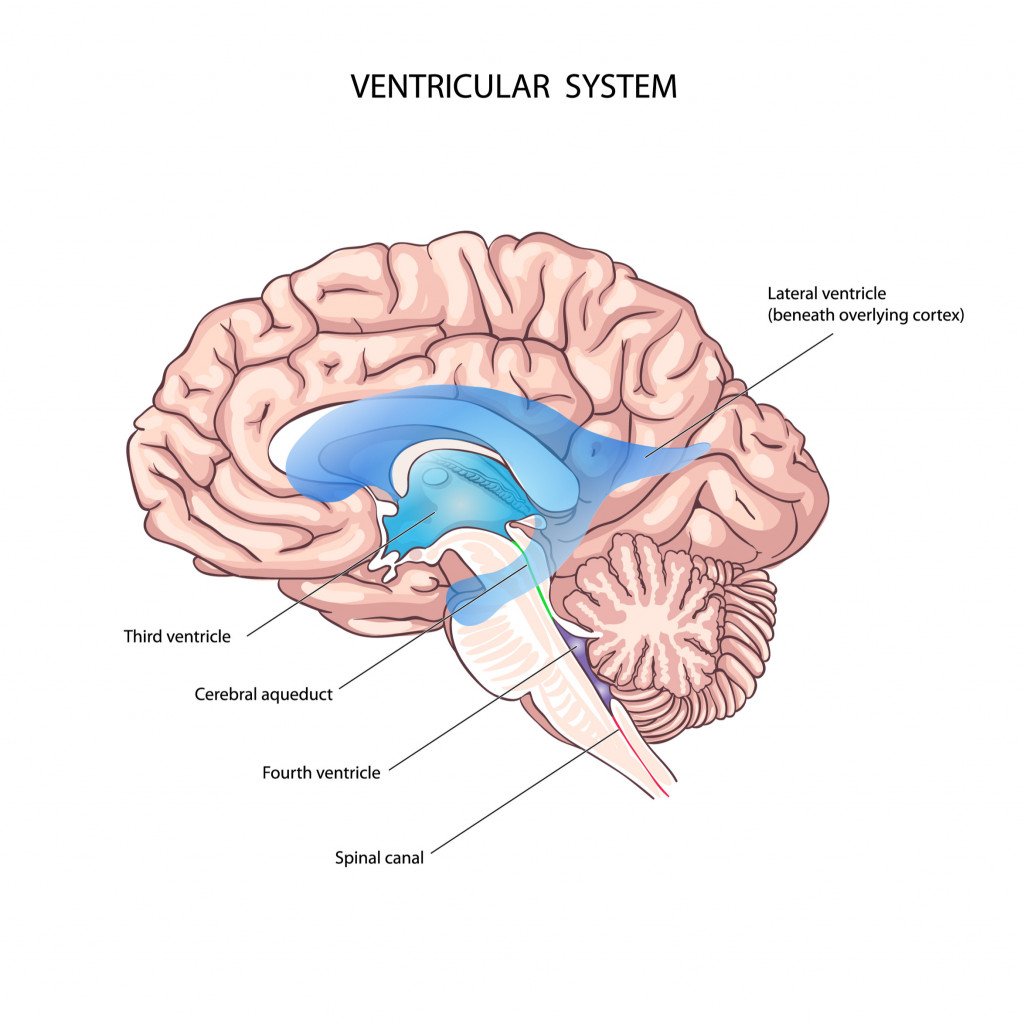

In response to confusing reports from the senses, the brain signals a region in the brainstem within the fourth ventricle, called the ‘Area postrema’.

This region signals the “vomiting center” in the medulla, to initiate vomiting in order to eliminate the hypothetical “ingested” toxin to defend the body. This is the leading theory explaining the evolutionary origins of motion sickness and its purpose, termed the “Toxin detector hypothesis”.

How Does A Motion Sickness Patch Work?

Motion sickness transdermal patches work by manipulating the evolutionary ‘toxin detector’ mechanism of the brain.

These patches contain a compound called Scopolamine (also called Devil’s breath), a type of alkaloid derived from plants of the Solanaceae family.

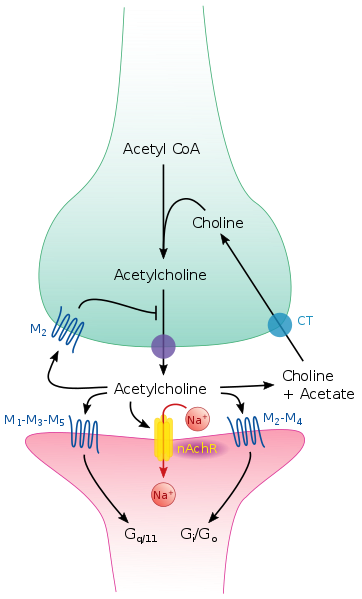

The brain regions involved in the emetic (vomiting) response communicate using a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine. Scopolamine competes with acetylcholine, and binds to its receptors on neurons, thereby inhibiting its effect. The state of acetylcholine is akin to that of a player in a game of ‘musical chair’, who is unable to find any seats because they are all being occupied by scopolamine.

The transdermal scopolamine patches are applied behind the ear, which slowly and consistently release the chemical, to be absorbed into the body through the skin. It binds to the acetylcholine receptors, which are present in high numbers in the neurons within the Area Postrema.

This inhibits the acetylcholine-based signaling from the brain from acting on the region, as the receptors in the region are already ‘jam-packed’ with scopolamine. The signal can no longer stimulate the Area Postrema. The vomiting center is not activated, so the vomiting response is not triggered by the brain.

Interestingly, scopolamine also has the reputation of being the ‘scariest drug in the world’. When used in inappropriate amounts, it can wipe out a person’s memory and even cause death. For this reason, there are records of it being used by criminals for manipulating, assaulting and robbing victims.

Summary

When we use transport of any kind, the brain receives conflicting information from the senses about the environment. As a result, it concludes that we have ingested a toxin, so it directs the body to vomit to eliminate the toxin. This is commonly termed motion sickness and can be experienced in ships, cars, camels, or even spacecraft. It is the result of our bodies and brains not being built to handle the artificial types of movement involved in transportation.

Fortunately, we have a quick fix in the form of adhesive patches that contain a chemical called scopolamine, which can inhibit the vomiting response triggered by the brain. It works by manipulating the communication pathways between neurons in the vomiting response that employ the neurotransmitter called acetylcholine. So, the next time you want to make sure that projectile vomiting doesn’t ruin your amusement park visit or road trip, you may want to consider a Scopolamine patch!

References (click to expand)

- Huppert, D., Benson, J., & Brandt, T. (2017, April 4). A Historical View of Motion Sickness—A Plague at Sea and on Land, Also with Military Impact. Frontiers in Neurology. Frontiers Media SA.

- Treisman, M. (1977, July 29). Motion Sickness: An Evolutionary Hypothesis. Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

- Pedigo, N. W., Jr., & Brizzee, K. R. (1985, February). Muscarinic cholinergic receptors in area postrema and brainstem areas regulating emesis. Brain Research Bulletin. Elsevier BV.