Table of Contents (click to expand)

Many cultures throughout history have not used numbers to count, but have relied on other methods like using their hands or estimating ratios. This is because humans are biologically only equipped with a primitive mental ability to sense quantities, which is further refined when humans learn number words in their culture. So, a lack of number words in a language denies the merger of two distinct systems – symbols and integers – that are necessary for an effective way to identify higher quantities.

How often have you counted the exact number of leaves on a tree? Or the number of bees swarming around a honeycomb? Given our tremendous numerical abilities, however demanding or tedious this task might be, it is doable. However, is it really useful? One must agree that deeming a quantity either large or small is often enough when it comes to thinking about seemingly uncountable things in our routine lives.

The notion of numbers has been shown to have critical importance to humans for centuries now. However, the contribution of culture is often dismissed when we contemplate them. Many scientists and anthropologists argue that humans can acquire the sense of numbers, the one-to-one correspondence between a word and a quantity, only if their language allows them to.

They argue that humans are biologically endowed with a primitive mental apparatus that can only achieve a crude sense of quantities. This ability is then further refined to the full-fledged ability to distinguish individual entities by acquiring the knowledge of number words.

This implies that language defines thought. Does this mean that a culture might be unable to count if they did not have number words in the first place? Or more simply, is the concept of numbers not present in all languages? A new research study strongly endorses this view.

Recommended Video for you:

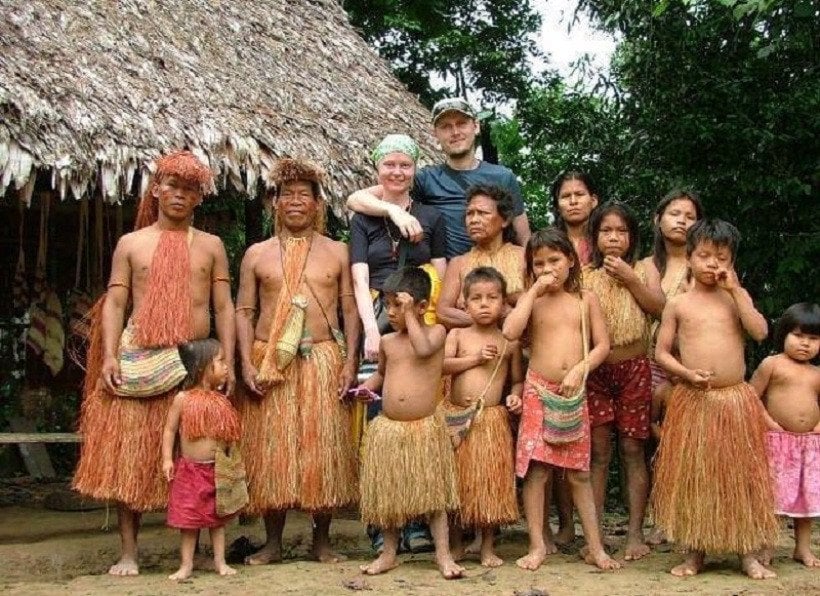

Numberless Cultures

All around us, we see people measuring time, counting calories and subtracting taxes, but a few remote cultures cannot even distinguish between 4 and 5. Piraha, an Amazonian tribe, is one such culture that speaks a numberless or anumeric language. People of this culture are remarkably poor at counting. Speakers actually find it difficult to count more than merely three objects!

Their language consists of three terms to describe a quantity. Hoi describes small quantities. A phonetic variation of hoi is used to describe somewhat larger amounts, and baagiso is used for many or a “cause to come together”. This depicts a representational system that assesses quantities based on ratios or the density of objects.

Caleb Everett’s research shows that these people lack a methodical numerical approach to recognize exact numbers and instead rely on a binary-esque or analog method to determine an approximate measure of what is more and what is less. Their one-to-one correspondence comes into play only when dealing with quantities less than 3.

Another anumeric culture is Munduruku and a few adults in Nicaragua who lack the ability to sort and distinguish, probably due to a lack of edification regarding number words.

Consider an experiment where scientists filled a can with nuts. The experimenters then removed these nuts one by one and asked the natives to signal when all the nuts have been removed. Many of the participants had trouble signaling even when the nuts weren’t more than 4 or 5!

Are These Tribes Cognitively Impeded?

Well, no. Their cognitive functions are completely intact. This was evident in their seamless adaption and sublime knowledge of their ecological environment. Yet they cannot precisely discriminate or count due to the poverty of necessary cognitive tools.

A decisive experiment would be to teach their children number words and then measure a few years later whether they have grasped a consistent and effective way to easily identify higher quantities.

Reading this, it is an understatement to say that we take our numerical abilities for granted. The one-to-one correspondence that the people of Piraha lack is supremely crucial, yet ubiquitous to our numeric cognition. Essentially, it might be our vocabulary that allows us to extend our recognition to larger quantities.

A lack of words denies the merger of two distinct systems – symbols and integers.

As one writer claims: “The capacity to represent positive integers is a cultural construction that transcends core knowledge.”

We’re biologically endowed with a mental module that differentiates small from large quantities or simply ratios, and not a mental space that maps individual numbers. The argument can be further cemented when one recalls that, for a considerable portion of our 200,000-year existence, humans had no means of representing quantities distinctly. Historically, people relying on symbols and numbers are the anolamous ones!

In his book Numbers and the Making of Us, Caleb Everett explains how we invented numbers and consequently reoriented human experience for posterity. However, critics argue otherwise and claim that the brain is predisposed for numeracy.

However, if numeracy is natural, why is learning numbers such a painstaking task for children? Children are often required to rote-learn a table that maps different symbols to a quantity incremented by one. We take this successor principle for granted now, but it takes almost 3 years and extensive practice to wrap our heads around it as children.

This mental apparatus to distinguish quantities has also been found in other animals, such as dolphins, monkeys, chimpanzees and parrots. Moreover, it is shown that these abilities can be sharpened when these animals are introduced to similar cognitive tools!

How Did We Invent Numbers?

It seems that our ancestors’ propensity to count arose from referring to an instrument that possessed distinct pendent features, to each of which they could mentally assign the number of animals in a herd or the fruits on a tree. This tool also had to be palpable and easily used. This instrument, of course, was our hand!

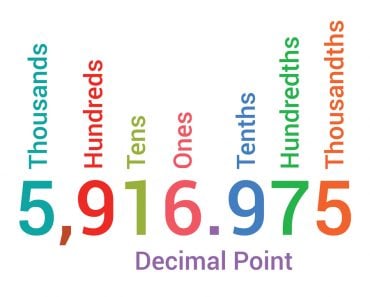

It is no surprise that our numerical system is based on a Base-10 numeric system, even though Base-12 has shown to be more logical. This is because we began to count on our fingers. Base-10 feels more natural as in: 16 = 10 + 6 and 51 = 5 x 10 + 1.

There are speculations that we inherited our numeric tongue from a proto-Indo-European language that was decimally based. This could be why the word for “five” in many languages is derived from the word for “hand”.

Our proficiency to count isn’t therefore solely credited to our aptitude for language and our natural tendency to look at our hands, but also to the critical decision in our evolutionary history to walk upright on two legs. However, no one is really sure when we started to count because no one knows when language first sprung into existence.

What Are The Consequences Of These Claims?

One pivotal consequence that researchers cite is the illusion of time. Because the concept of numbers is a human construct, the values we assign to time are also meretricious.

Ascribing numbers to time in order to acquire a measure of its rate of flow highlights our irrational need to categorize or seek a pattern in seemingly pattern-less things. Time is not real in any physical sense and it is particularly non-existent to numberless people. We derived the standard Base-60 numeric system for the measurement of time from Mesopotamia a few millennia ago.

I want to stress here that counting is wildly important for human culture, but nature has implanted a module in us that is only concerned with ratios. Counting does seem to have an evolutionary purpose, as someone who could keep a count of his stored seeds or fruits had an advantage over someone who could not, for example.

But how consequential would be knowing the difference between 1000 and 1001?

The difference between 1 and 1000 is important, but the difference between 1000 and 1001 is negligible, or it is fair to say, inconsequential.

Whether we have an innate sense of numbers has been heavily debated in philosophical, theological and now neurological circles. In other words, we wonder whether numbers exist independently of us?

References (click to expand)

- Everett, C., & Madora, K. (2011, November 3). Quantity Recognition Among Speakers of an Anumeric Language. Cognitive Science. Wiley.

- Núñez, R. E. (2017, June). Is There Really an Evolved Capacity for Number?. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. Elsevier BV.

- Numbers and the Making of Us — Caleb Everett. Harvard University Press

- Why do humans have numbers: are they cultural or innate?. Aeon