Table of Contents (click to expand)

There are many claims about how reading fiction can change your life, but could the habit of reading—particularly reading fiction—alter your brain?

A good book can change your life, but can it also change your brain?

According to Canadian psychologist Steven Pinker, reading, and thereby literacy, could cause changes in an individual’s behavior that then collectively lead to a decline in violence and create a more free and tolerant society. Reading, especially fiction, significantly improves a readers’ capacity for empathy.

While that sounds wonderful, in what manner does reading cause such changes in our brain?

Recommended Video for you:

The Reading Brain

Stories are powerful tools of communication. They enable us to live a thousand different lives and experience a hundred realities that would otherwise be physically impossible So, what exactly happens in our heads when we read these types of stories?

Reading boasts an array of benefits, ranging from enhancing imagination to improving empathy in individuals. The short-term effects of reading include a sharp increase in comprehension of language, as well as in being empathetic and introspective (Source).

Reading heightens the functioning of the following brain regions:

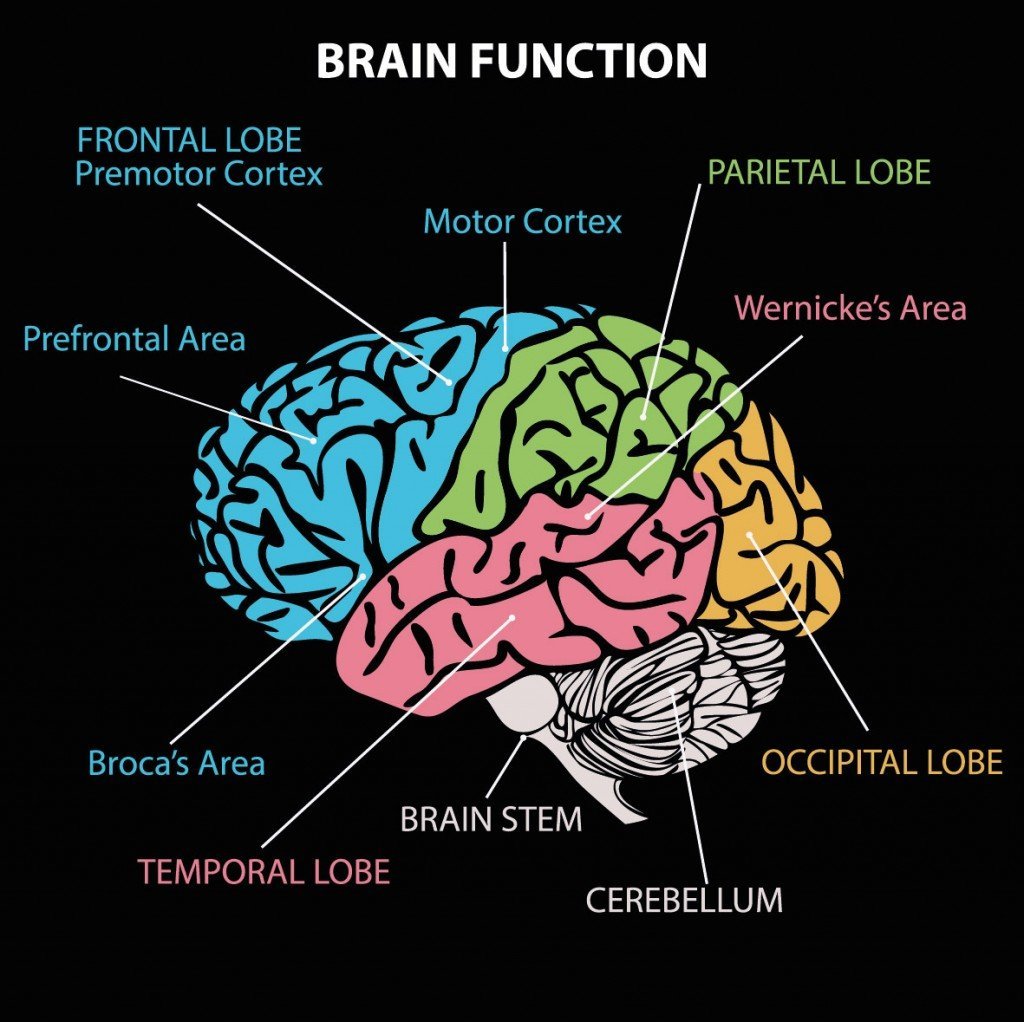

- The limbic system, which is the part of the brain involved with learning, emotions, and the formation of memories.

- The Visual Word Form Area of the brain helps us visualize words as images.

- Wernicke’s area is responsible for language processing.

- Broca’s area is involved in speech formation.

- The prefrontal cortex, which is linked to the planning of complex thought processes, the expression of personality, decision-making, regulating social behavior, and an overall increase in goal-oriented behavior.

The Brain On Fiction

Reading a fictional story is akin to being in a simulation. It allows us to live out a reality that we construct in our brain using written words. Through reading, we can transcend our single life to experience and live a multitude of them.

Fiction reading stimulates the same neural networks in our brain that are activated when humans are subjected to any kind of simulation.

There are primarily two networks in the brain that light up when we read a story:

- A network that allows us to construct scenes in our head and imagine the physical spaces that are being described.

- A network that allows us to think about the characters, their lives, and their mental states.

Both these networks function separately. However, researchers have observed a similarity between the network that allows us to understand the mental states of fictional characters and the network that allows us to understand the thoughts and actions of other people.

This ability to put oneself in others’ shoes is known as the Theory of Mind (ToM).

Readers have their favorite genres, from fiction, including romance, horror, and thriller, to nonfiction literature. Interestingly, reading literary and romantic fiction has shown the highest correlation with increasing ToM.

Exposure to these genres of fiction can help an individual better understand the thoughts and needs of others.

Hence, reading serves as a simulation practice that allows readers to experience hypothetical realities, different circumstances, and other people’s lives. This then grants them the ability to become better at understanding the social needs of others in the real world.

Reading Fiction Changes The Structure Of The Brain

The structure of the brain of an individual might differ owing to their reading habits. Reading can even change certain regions of the brain during the early years of development. (Source)

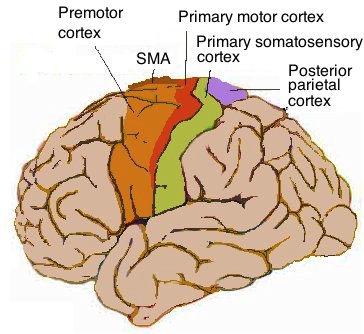

Reading a book places us in the mind and body of the protagonist. This experience stimulates the parts of the brain responsible for our sensations (somatosensory cortex) and movement (motor cortex). Stimulation of these brain areas strengthens the connectivity of neurons within them. It is also seen that the strengthening of the somatosensory and motor networks in the brain persists even after some time has passed since reading. (Source)

In a study conducted by scientists from Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, a group of undergraduates was scanned under functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) over a period of time as they read the thriller Pompeii by Robert Harris.

The scientists periodically conducted the fMRI after the readers had completed reading a few sections of the book. Increased activity was seen in the left hemisphere, which has areas of the brain related to language perception, and the central sulcus, which is the primary motor cortex of the brain and plays a role in the exercise of visual imagination.

The increased activity in these brain areas was retained in the participants even when not reading, which might signify long-term changes in brain activity brought about by reading.

Research has also found that frequently reading literature is associated with a lowered loss of intelligible speech and greater memory recall, thereby reducing the risk of dementia-related disorders in old age.

Conclusion

“A reader lives a thousand lives before they die…” – George R. R. Martin.

This experience of a thousand lives also leaves an impression on our brain. It strengthens the networks that allow us to understand others better. It also brings about changes in the brain areas that are involved in language, speech, visualizations, and complex thoughts.

References (click to expand)

- Houston, S. M., Lebel, C., Katzir, T., Manis, F. R., Kan, E., Rodriguez, G. G., & Sowell, E. R. (2014, March 26). Reading skill and structural brain development. NeuroReport. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health).

- Berns, G. S., Blaine, K., Prietula, M. J., & Pye, B. E. (2013, December). Short- and Long-Term Effects of a Novel on Connectivity in the Brain. Brain Connectivity. Mary Ann Liebert Inc.

- Tamir, D. I., Bricker, A. B., Dodell-Feder, D., & Mitchell, J. P. (2015, September 4). Reading fiction and reading minds: the role of simulation in the default network. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. Oxford University Press (OUP).