Table of Contents (click to expand)

Vampires—as the society that interacted with them developed—became less fearsome as their existence (or the lack thereof) became clear.

For those of you who haven’t read Stephanie Meyers’ Twilight Saga or seen its film adaptation, Robert Pattinson’s “portrayal” of the immortal vampire Edward Cullen exposed the world to a teenage romance that has come to define the other-worldly side of love.

Nosferatu did the same thing to cinema before the sparkly-skinned actor. Nosferatu’s character was a relatable figure to the target audience that was experiencing its own changes (adolescence is a wild ride, after all). He, however, was not the first vampire trend setter to take the fictional world by storm.

That credit goes to Dracula, immortal landlord, evil bloodsucker and Bram Stoker’s legendary brainchild.

Recommended Video for you:

The Beginning Of The Vampire

Most cultures around the world have myths about a creature similar to vampires. The Mesopotamian Lamashtu, a mix of a lion and donkey, the Australian Yara-ma-yha, the Romani moroi, and the Slavic undead were all bloodsuckers.

Though the specifics may be different, the common factor—blood and life force as the primary dietary source—remains the identifying feature. The word vampire itself is a European term used to describe the undead, garlic- and holy water-fearing variety of bloodsuckers.

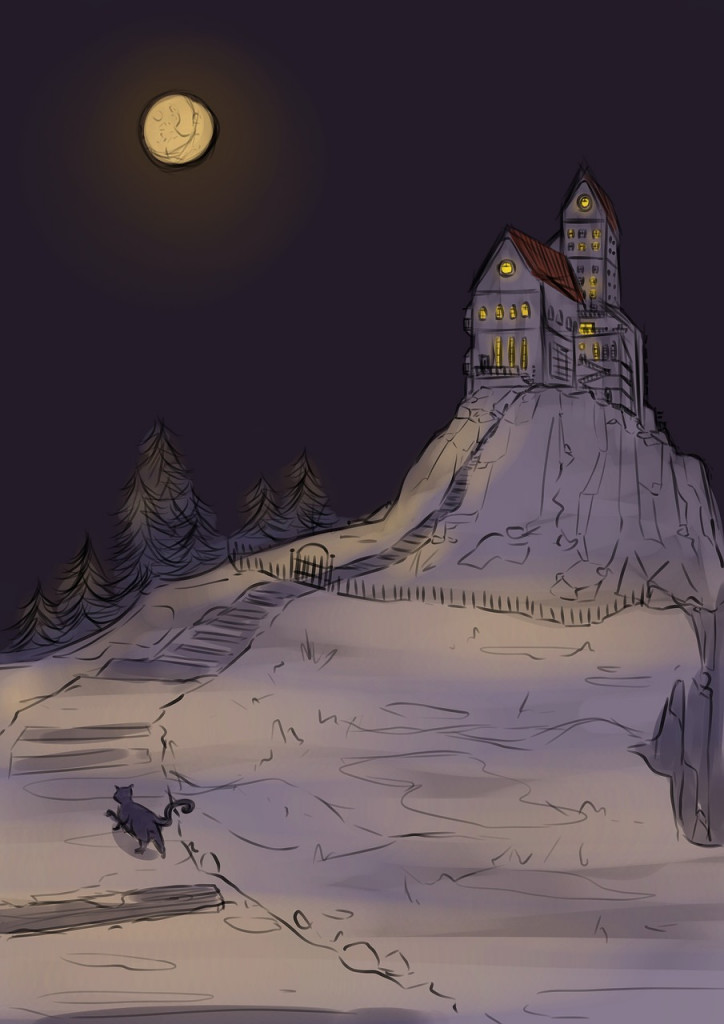

The vampire myth was popular among medieval Europeans, especially in the East. During times of disease and plague, they became vectors of superstition for people who did not understand the nature of contagions. These people dealt with many corpses and corpse-like ill people, which then manifested in the stories of those who lived after them. Basically, if a medieval peasant had a relative who died of the plague, he could make up a story about how his dead relative had once come back to drink his blood.

This local myth developed into the one we now recognize after its popularization in 18th and 19th century literature.

While Byron’s The Giaour, Polidori’s The Vampyre and Sheridan Le Fanu’s La Morte Amoureuse were some of the works that utilized this monstrous subject, Bram Stoker’s Dracula remains the seminal work of fiction that got us to where we are.

Dracula relied on the local traditions about a vampire’s weaknesses and strengths, but added a few more traits that have expanded the trope.

The Birth Of Dracula

Dracula possibly finds inspiration in the 15th century Romanian prince of Wallachia, Vlad Dracul III, better known as Vlad the Impaler. Vlad’s father, Vlad II of Wallachia adopted the name Dracul upon joining the Order of the Dragon (a Catholic order to protect the Holy Roman Empire from the Ottoman threat).

Dracul literally means the Dragon, which is funny, as “dracul(a)” is practically synonymous with vampire, a mythical being, but it dragon, another fearsome and majestic mythical being. In modern Romanian and also Wallachian, drac is used to refer to a devil.

Another possible source of inspiration is the Hungarian Countess Elizabeth Bathory, who was thought to have murdered young women to either bathe in or drink their blood to remain youthful herself. The common link between Dracula and Bathory, besides the blood, is Transylvania, which was controlled by the latter’s family.

The Trope Manifests

Stoker gave his readers a story that was worth repeating. Over time, it impressed upon the audience to the extent that it became a curiosity, one further sated by those who started using the vampire trope in their own works. This phenomenon was primarily carried on in European and English-speaking (and reading) traditions.

Other European languages also capitalized on the trope, but very few were mainstream enough to be of great consideration here (which is not to say that they weren’t equally seminal in their own spheres of influence). Obviously, there is a broad gap between Stoker’s ugly charting of human cruelty and depravity and the redemption-seeking, breathtaking vampire forms we see today. This is where the retelling bit comes in. When a story or theme is repeated enough, it modifies itself in the image of its teller.

Eventually, after the 1970s (when vampires moved from brutal villains to sympathetic anti-heroes), the trope evolved with the audience, which had started to look at monstrosities in a kinder light. Television provided a more digestible portrayal (both for costume and audience reasons). Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire, unlike most in the trope, whih existed within the characteristics of ‘vampire’ defined by Dracula, instead romanticized the myth for a modern audience.

Of course, as humans, we cannot predict the true extent of mortality, so all vampire tropes are somewhat based on guesswork. In times of death and sickness, vampires were evil beings who preyed on the good and faithful. In times of modern healthcare and a developed emphasis on love and individuality, the myths evolve to suit the acceptance we have established for the otherworldly.

One wonders if it would be possible, without the Age of Enlightenment and greater scientific thinking, to accept folklore. It seems that disassociating from the advancement of our world the existence of the Barnabas Collins and the Louis de Pointe du Lacs versions (both in the big leagues of cinematic vampiric depiction) would be the true fiction in this scenario. Perhaps the newer arrangements of power and authority in the trope also motivated the allegory in the depiction of power, where power dynamics, capitalist ‘indulgence’ and acceptance of what was previously an ‘Other’ take center stage.

Conclusion

Stoker’s novel became one of the most well-known works of Gothic fiction and led to the proliferation of the vampire trope in countless forms. It is him that we must thank for Count von Count and Damon Salvatore. Like the vampire, the vampire trope now seems immortal, though perhaps all those Slavs who spent years staking dead bodies and tracking garlic-fearing corpses would shudder in their un-undead graves if they were to read about the undying “teenage” love between a vampire and a human!

References (click to expand)

- Veldman-Genz, C. (2011). Serial Experiments in Popular Culture: The Resignification of Gothic Symbology in Anita Blake Vampire Hunter and the Twilight Series. Bringing Light to Twilight. Palgrave Macmillan US.

- Lindop, S. (2017). It’s a Love Story—Involving Vampires: The Cinematic Trope of the Wedded Bloodsucker. Hospitality, Rape and Consent in Vampire Popular Culture. Springer International Publishing.

- Winnubst, S. (2003). Vampires, anxieties, and dreams: Race and sex in the contemporary United States. Hypatia, 18(3), 1-20.