Table of Contents (click to expand)

Queuing theory was first proposed by Danish engineer Agner Krarup Erlang. The theory can be used to optimize the design of lines and to determine the best way to serve customers. It has been applied to a wide range of topics, including health care and transportation.

Waiting in lines is one of the most resented activities we voluntarily participate in throughout our daily lives. One estimate reports that Americans – on average – spend a staggering 37 billion hours per year waiting lines! Part of the reason why online shopping is so exulting is that it completely removes the scornful abuse of our time and patience that we experience while standing in lines.

This article is for the impatient, the relentless, the people cursing their luck, incessantly tapping their feet, denouncing their faith in the gods of fortune and justice for they only came to buy a toothbrush. Moreover, as the lines adjacent to them fly by, a pall of regret slides over — “In all the lines in the world, I had to choose this one.”

Don’t worry, we’ve got you. The following tips are guidelines lent by experts to help you choose a faster line the next time you go grocery shopping.

Recommended Video for you:

Queuing Theory

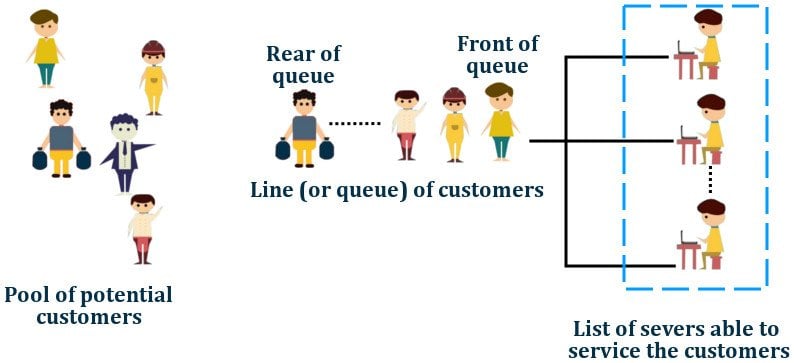

Queuing Theory is this emerging theory that works out the mathematics involved in waiting lines. Its area of research lies between system operations research and behavioral economics, and applies to studying business models and implementing device analysis.

And one can quite easily identify the resemblance between customers arriving at a counter and inputs arriving at a device.

The theory was set in motion when Agner Erlang, a young engineer at the Copenhagen telephone exchange, was trying to figure out the optimum number of phone lines for the city’s switchboard. He later published a paper backing his theory that was heavily based on probabilistic distributions. The theory is now driven by behavioral economics.

The theory earned its fair gain of attention in pop-science when we realized how its findings were directly applicable to our daily lives. It showed the potential to alleviate – or in some cases, altogether eradicate – the cringiest of our third-world problems.

The theory earned its fair gain of attention in pop-science when we realized how its findings were directly applicable to our daily lives. It showed the potential to alleviate – or in some cases, altogether eradicate – the cringiest of our third-world problems.

The ‘wait’ depends on the people served before you, the number of servers or counters in operation, and the amount of time required to serve each individual customer. The design of lines is also a huge factor. Whether there are parallel lines leading to different counters or a single line dividing into multiple counters can provide an approximate indication of the pace at which the line will move. Or, it could function on a first come-first serve basis or priority basis, such as in hospitals. All of these variables must be considered.

Waiting can often get ugly. The idea of someone cutting your line and being served before you is undoubtedly abhorrent and infuriating. People tend to perceive such seemingly insignificant acts to be at extreme discord with their social morals. Messing around with their patience is deemed highly unscrupulous, they feel manipulated and judge the management to be bad.

A large queue can discourage customers and force them to not shop in the first place. A shorter line not only keeps them at peace, but also allows a shop to take money from customers as swiftly as possible. Companies now employ queuing experts to assist them in solving these unavoidable problems.

The act of pleasing customers is ridiculous, to the extent that some shops host live shows featuring pianists or guitarists to keep customers entertained. Other cheap options – and the most prevalent ones – are the installment of televisions.

The Tips To Find The Fastest Line

1. Go Left

Research suggests that most people are right-handed and tend to swerve right when challenged with choosing a line. In this way, a glut of people tend to aggregate to the right, so you should veer to the left to find a shorter line.

However, this doesn’t guarantee respite. Despite the longer length of the line on the right, it could move faster if it’s being served faster than the shorter line on the left. However, it seems that we tend to find psychological comfort in resorting to shorter lines.

A study has found that in a choice between faster, longer lines and shorter, slower lines, people tend to choose the latter almost every time!

2. Get In Line With Shoppers Who Have Full Carts

This sounds highly counterproductive, but queuing experts reason that cashiers become more dexterous and quicker in their parsing when they are facing a large number of products, as they want to get rid of them as quickly as possible.

3. Study The Customers And Their Carts

According to Prof. Marsden, a leading expert in queuing theory, the movement of a line doesn’t solely depend on the number of people ahead of you, but also their age and what they’re buying. For instance, older people will take a longer time during checkouts due to their infirmity while carrying bags or executing digital transactions.

Also, what they are buying is equally important. Two packets of the same brand of chips will take a shorter time to pass than two totally different items, particularly vegetables, as they typically cannot be scanned. Self-service checkout is also highly recommended to check out faster, at the expense of human contact.

4. Serpentine Lines

Research has continually shown that the line variant that is the most efficient and fair is a serpentine line. Like the name suggests, people are asked to stand in one long single precarious line. However, there are multiple counters and servers.

The person at the front goes to the first counter, the second to the second and so on, depending on the number of counters. The design leaves no room for indecision or contemplation, yet people still prefer shorter parallel lines, due to the already mentioned psychological relief.

Also, a serpentine line requires larger stores that can contain larger, winding lines.

5. Avoid Obstructions

Experts suggest that waiting time is perceived to be stretched when the view between us and the cashier is obstructed by any object, such as a pillar or shelves.

Again, unreasonable psychological comfort is at work here. Researchers reason that witnessing the cashier do his or her work and thinning the line soothes our frustration. An obstruction denies this feedback and adds to our agitation.

It’s All In Your Head!

Other miscellaneous tips are to remove hangers from clothes or present your products with the bar code facing the cashier to save time. Or, there’s the good ol’ ‘let’s-split’ strategy, where each family member or friend is assigned to different lines.

However, the point I want to stress here is that the apprehension surrounding waiting, to a small extent, is all in your head. A research found that, on average, people overestimate how long they waited in a given line by 36%.

Technological advancements have supplemented this by warping our sense of patience and elapsed time. According to Swedish economist Staffan Linder, “As a society becomes more affluent, its time becomes more valuable.” Think about it, when was the last time you waited while a Facebook video buffered and didn’t lose your nerves? Or rolled your eyes when you found out that the video your friend tagged you in lasts two minutes and ten seconds.

Compare this to the era of flip phones, now a certain relic, when tapping the ‘globe’ icon and patiently waiting for the browser to load took fifteen minutes itself!

Ironically, distraction is a handy tool when it comes to mollifying the waiting process. Distraction has been shown to accelerate the flow of time, or has at least proven to make it less conspicuous. Idleness or painstaking boredom evaporates when we are distracted, either by taking the road less traveled and talking to people or reading a book. Or, well, you could simply, scroll.