Table of Contents (click to expand)

We use muscle memory for motor skills, but the term has a second meaning that scientists use when they talk about the strength of individual muscles.

“Practice makes perfect” has a new, scientific spin to it—muscle memory. “Commit it to muscle memory” your music instructor might say when learning a series of chords, or your art teacher might say the same thing about making perfect freehand circles.

The goal behind practice and muscle memory is to be able to perform a task without thinking about it—effortlessly. However, do your muscles actually remember the skill?

Turns out, muscles do have memory, but not in the way you might think.

So, what exactly is muscle memory?

Recommended Video for you:

Muscle Memory Definition

Muscle memory can mean different things, depending on who you ask.

If you ask a well-read non-scientist, they’ll give you an answer similar to the one above. Muscle memory, they’ll say, is when your brain has learned a motor task so well that you can perform the task without conscious effort.

Now, if you ask a scientist, a neuroscientist, or someone who studies muscles, they’ll tell you that muscle memory is the cellular memory of individual muscle cells. The term refers to the changes in muscle cells caused by exercise. It is as if the muscles remember the effects of exercise, even if you no longer regularly exercise.

Muscle Memory Examples

The fact that you know how to ride a bike and will likely never forget is due to the first meaning of the word. It’s more brain memory than muscle memory.

The muscles remembering the effect of exercise, even if you no longer regularly exercise, due to the cellular changes the activity caused in a muscle cell, is the more scientific take on muscle memory.

Muscle Memory Of The Brain

Muscle memory of the brain is the brain learning a motor skill. Thus, it should be called “brain motor skills memory”, but that doesn’t have quite the same ring to it.

When you practice a skill, be it riding a cycle, swimming, learning choreography, or mastering the latest pop song on the guitar, you’re forcing your brain to coordinate between many different muscle movements.

The most relatable example is riding a bike. To successfully ride a bike, you need to keep your posture upright and maintain your center of balance, your legs need to rotate the pedals to get the wheels moving, and you need to maneuver the handles with your arms. All this requires many simultaneous muscle movements to coordinate and puts your senses in overdrive.

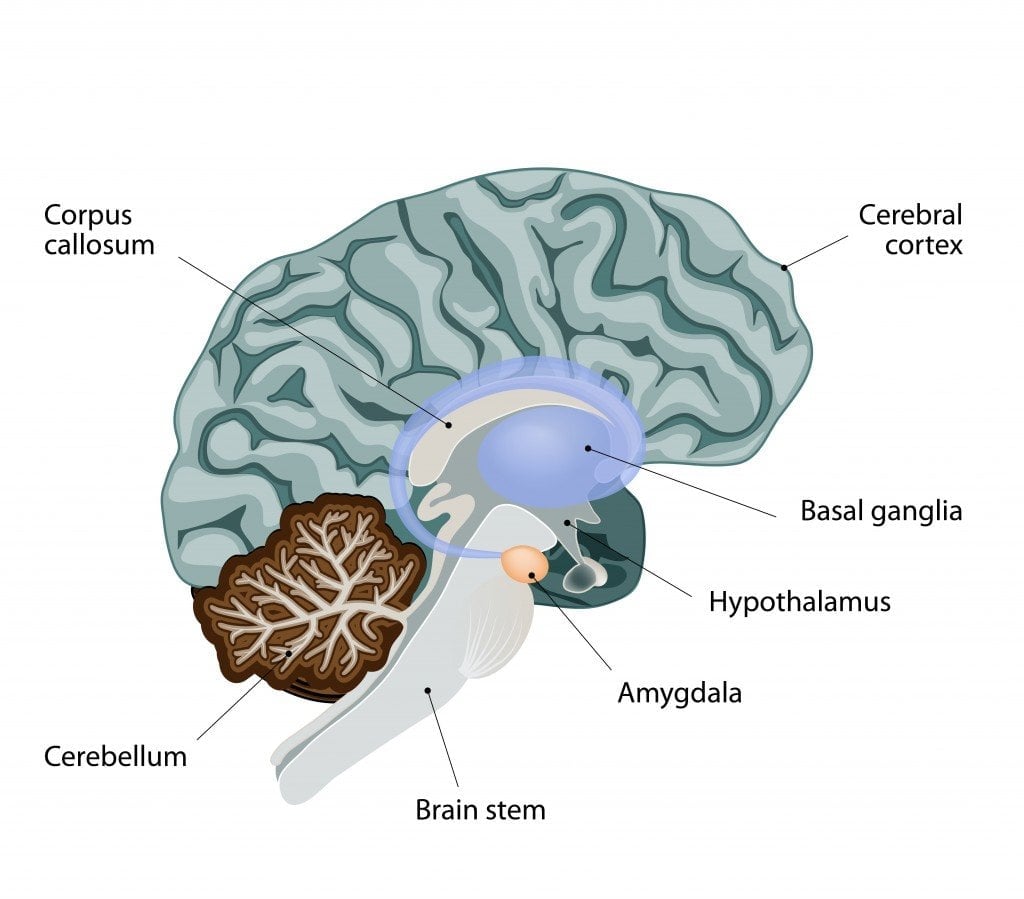

To coordinate these muscles, parts of the brain involved in motor movements, such as the cerebellum and motor cortices, are activated to move your muscles. These regions have neuronal pathways that allow us to perform complex motor tasks.

The brain is made up of neurons, and these neurons connect to make many intersecting pathways or roads. Along these neuronal pathways, the brain receives information from and sends information to various parts of the body.

However, these neuronal pathways aren’t initially paved well. It is with practice and constant use that these neuronal pathways get smoother and allow information to pass more efficiently.

Soon, you won’t need to spend energy on remembering the finger positions for a C minor chord on the guitar.

Musicians will relentlessly practice a piece until they can play it in their sleep. Dancers will rehearse until they can also perform it like second nature. Artists will draw for hours on end until they can depict a human face without needing to check a reference.

Muscle Memory Of Muscles

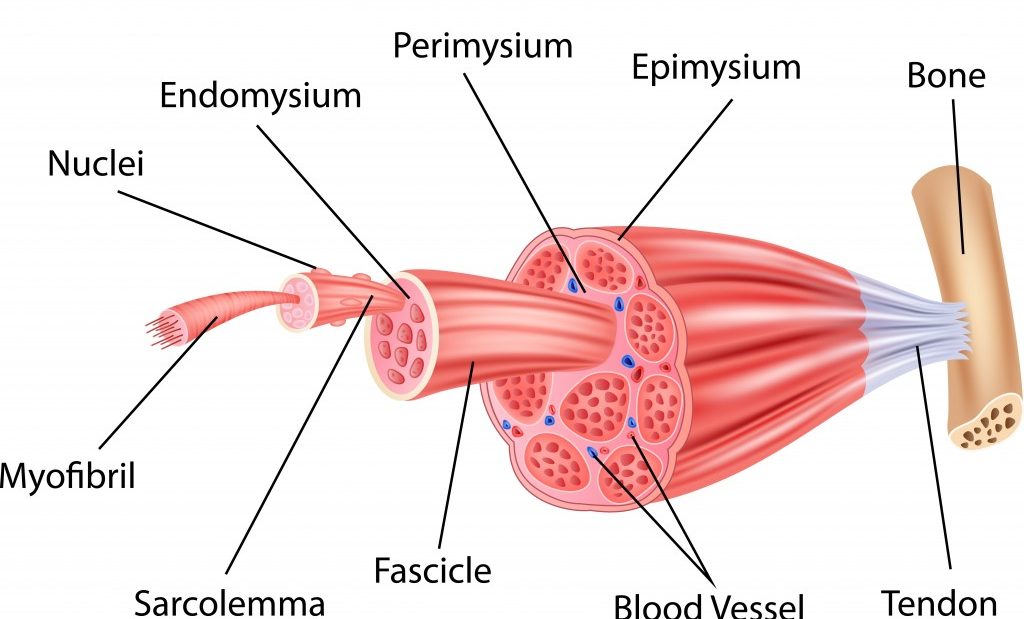

Muscles are composed of muscle fibers, with each muscle fiber made of muscle cells. Normally, one cell only has one nucleus (a portion of the cell that contains the DNA, the instruction manual of the cell). However, muscle cells are one of the few types of cells that have multiple nuclei—called myonuclei—in them.

Exercise strains the muscles. This strain results in tired and damaged muscles that the body needs to repair. In this process of repair, the muscles add new cells and myonuclei to existing cells. This increases muscle mass, which eventually makes the muscles—and by extension you—stronger. This increase in muscle mass due to vigorous exercise is called hypertrophy.

Research into the effect of exercise on the long-term health of one’s muscles shows that the gained myonuclei are not lost, even after you stop exercising. Once you stop exercising, your muscles will lose the extra muscle mass (atrophy), but the new myonuclei that have been added remain. The loss of muscle mass is a loss of the proteins in the muscle.

When you do get back to exercising, you’re likely to regain your strength faster because of the previously gained myonuclei. The gained myonuclei might be involved in the process of protein synthesis and other cellular changes, which, researchers hypothesize, gives the muscle cells a kind of memory of that particular exercise. This “memory” might be easier to gain the younger you are, and the memory may last for many years (15 years, according to one estimate).

A Final Word

Research on muscle memory is recent, and the fact that added myonuclei give a memory of strength is only a hypothesis. There are other factors, such as epigenetic changes (changes made to the proteins and chemicals attached on top of the DNA), which may also affect muscle strength.

Also, while your muscles seem to remember your time in the gym, the brain remembers that the sequence of moves you made in the gym works to make you less clumsy, both at the gym and outside it! So, whether you’re trying to work on a new skill or are trying to hit the gym again, thank your muscle memory for not making you start all over again.

References (click to expand)

- Tian, W., & Chen, S. (2021, February 25). Neurotransmitters, Cell Types, and Circuit Mechanisms of Motor Skill Learning and Clinical Applications. Frontiers in Neurology. Frontiers Media SA.

- Tomassini, V., Jbabdi, S., Kincses, Z. T., Bosnell, R., Douaud, G., Pozzilli, C., … Johansen-Berg, H. (2011, February 14). Structural and functional bases for individual differences in motor learning. Human Brain Mapping. Wiley.

- Eftestøl, E., Psilander, N., Cumming, K. T., Juvkam, I., Ekblom, M., Sunding, K., … Gundersen, K. (2020, February 1). Muscle memory: are myonuclei ever lost?. Journal of Applied Physiology. American Physiological Society.

- Gundersen, K., Bruusgaard, J. C., Egner, I. M., Eftestøl, E., & Bengtsen, M. (2018, August 25). Muscle memory: virtues of your youth?. The Journal of Physiology. Wiley.

- Gundersen, K. (2016, January 1). Muscle memory and a new cellular model for muscle atrophy and hypertrophy. (S. L. Lindstedt & H. H. Hoppeler, Eds.), Journal of Experimental Biology. The Company of Biologists.