Table of Contents (click to expand)

The Abilene Paradox is a situation in which a group of people collectively make a decision that is contrary to what they would have individually wanted to do. The paradox occurs when the members of the group suppress their doubts and reservations about the decision in order to maintain harmony within the group. The result is often disastrous, as the group ends up taking a course of action that is contrary to their original intentions.

“Let’s get in the car, go to Abilene and have dinner at the cafeteria,” suggested Jerry Harvey’s father-in-law impulsively. Jerry Harvey found this ridiculous, for to reach Abilene, the family of in-laws and his wife, who were already suffering in the sweltering 104-degree heat torturing all of Coleman, Texas, had to trudge through a 53-mile desert seething with dust storms in a non-air conditioned Buick.

Surprisingly, his wife didn’t find the suggestion reprehensible. She immediately agreed: “Sounds like a great idea. I’d like to go. How about you, Jerry?” she responded. Assessing the fuss caused by any dissent, Jerry also acquiesced. However, in a final attempt to avoid the discomfort, Jerry, with a sense of foreboding, appended his agreement with “I just hope your mother wants to go.”

“Of course,” his mother-in-law remarked, “I haven’t been to Abilene in a long time.”

Jerry’s fears actualized, the heat was brutal and the food served in the cafeteria “provided first-rate testimonial material for antacid commercials.” After tasting dust for 4 hours and some 103 miles, the family arrived back in Coleman, relishing a fan’s breeze in their apartment. The room was permeated by a thick silence until Jerry asked: “That was a great trip, wasn’t it?”

His mother-in-law annoyingly blurted out how she originally preferred staying in Coleman and thought the idea to voluntarily jump into a boiling pot was outright idiotic. Apparently, she had only agreed because the other three had agreed. “I wouldn’t have gone if you all hadn’t pressured me into it,” she defended herself. Her daughter echoed her thoughts, “I just went along to be sociable and keep you happy. I would have had to be crazy to want to go out in heat like that,” she blamed them. Lastly, the poor father admitted that he never wished to visit Abilene either; he reasoned his whim by saying, “I just thought you might be bored. You visit so seldom and I wanted to be sure you enjoyed it.”

What in the world had just happened? the whole family pondered in silence. Harvey had just witnessed an absurd paradox. He writes in his widely acclaimed paper: “Here we were, four reasonably sensible people who, of our own volition, had just taken a 106-mile trip across a godforsaken desert in furnace-like temperatures through a cloud-like dust storm to eat unpalatable food at a hole-in-the-wall cafeteria in Abilene, when none of us had really wanted to go.” He adds: “In fact, to be more accurate, we’d done just the opposite of what we wanted to do. The whole situation simply didn’t make sense.” Harvey referred to this absurdity as the Abilene Paradox.

Recommended Video for you:

One Ticket To Abilene, Please

After the episode in Coleman, Harvey, a management expert, observed that the peculiar phenomenon also occurred in couples, families and members of an organization, including the government. The phenomenon occurs whenever a group of people attempts to reach an agreement while collectively solving a difficult problem. However, paradoxically, the agreement they finally arrive at is exactly contrary to what one would rationally expect. Simply stated, “Organizations frequently take actions in contradiction to what they really want to do and therefore defeat the very purposes they are trying to achieve.”

He elucidated the paradox in a groundbreaking paper called The Abilene Paradox: The Management of Agreement. The name was inspired by the whimsical anecdote I mentioned in the prelude. To explain the paradox, Harvey cites three scenarios: first is his miserable journey, second is a hypothetical scenario involving a small industry, and the third is a real event that led to terrible political consequences.

While Harvey and his family only suffered a minor inconvenience, in a profitable organization, the same paradox could also cause a huge economic loss. Harvey’s hypothetical scenario involves a research director, a vice president and the president of a small industry. To increase his firm’s profits, the president decides to take on a new project. However, it only looks good on paper – it is, in reality, obviously unfeasible due to a lack of the required technology – a fact the other two are privately aware of.

However, the president cannot turn his back now on this widely publicized project, as it would invite ignominy and devalue his subordinates’ commitment. Similarly, the vice-president and the director must suppress their doubts, as it might devalue the president’s commitment to the project and potentially lead to their dismissal from the firm. Harvey calls this contradiction action anxiety, which was famously described by Shakespeare himself: To be, or not to be, that is the question: Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Or to take Arms against a Sea of troubles, And by opposing end them: to die, to sleep.

The anxiety fuels negative fantasies, which include losing the job or ignominy. To avoid these scenarios, the members proceed to take the risk – the firm issues a huge budget. The project, of course, doesn’t deliver and leads to a devastating loss, which is consequently compensated by firing several employees. But what drives the anxiety? Psychologists believe that it is primarily the fear of ostracism. Being inextricably social creatures, they suggest that ostracism is the cruelest punishment one can devise. It is because of our fundamental need to connect, engage and be understood that no one wants to be perceived as the one who’s not a “team player”.

However, there is a paradox within the paradox here; what drove them to take the risk and tread the alternative path eventually led them to the same destination — the project failed miserably. There is an outbreak of distrust, and to defend oneself, each blames the other two. The conduct of the members was completely in contradiction to the data they had, and as a result, rather than solving it, they only compounded the problem. As Harvey writes: “Symbolically, the organization has boarded a bus to Abilene.”

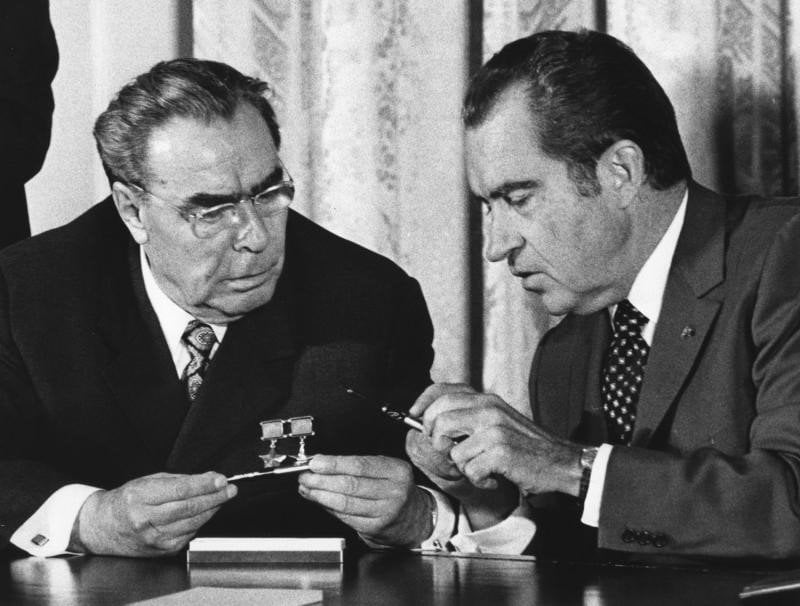

The real-life scenario Harvey cites is the infamous Watergate scandal that ruined the legacy of Nixon’s presidency. Nixon’s close subordinates abided by his idea to “peek”, despite being aware of its immoral and illegal nature. The Washington Post courageously revealed how the much-condemned events unfolded in the exact manner that the paradox predicts. The elements were eerily similar: participants had their reservations and doubts, but decided to suppress them, as dissent could potentially cost them their jobs or invite ostracism. The key authorities revealed how they didn’t want to be labeled as a traitor and wanted to cement their positions as loyal “team players”. Their loyalty to the president proved to take precedence over the moral good. The members, after the catastrophe, could only blame each other.

The Symptoms

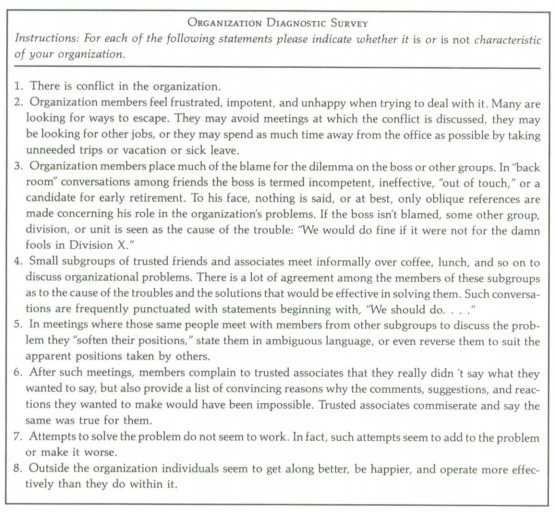

Throughout the paper, Harvey repeatedly emphasizes that the paradox occurs while managing agreement, not conflict. “The inability to manage agreement, not the inability to manage conflict, is the essential symptom that defines organizations caught in the Abilene Paradox.” The boundary separating them can often become blurred, so to mitigate the confusion, Harvey devised a questionnaire or a checklist to determine whether your organization is managing conflict or agreement.

If you have arrived at the conclusion that your team is managing agreement, then the second step is to investigate whether you’re headed towards Abilene. If the conduct of your team exhibits these symptoms, you might want to rethink your strategies.

- Members privately acknowledge, as individuals, that they are facing a problem, whether it was boredom in Harvey’s case or low profits in the industry’s case.

- Members privately acknowledge, as individuals, the steps required to solve the problem or satisfy their collective desires.

- However, miscommunication or a fear of exclusion ensures that their beliefs aren’t adequately expressed. In fact, they express what is contrary to their beliefs, thereby skewing the collective reality. For instance, Harvey’s family communicated inaccurate data by agreeing that visiting Abilene was a great idea, despite personally, resenting the idea. This completely misrepresented the true collective reality of the situation.

- Now trapped in the paradox, the members take collective actions contrary to what they desired or what was ideally supposed to be done, thereby arriving at an outcome that is counterproductive to the group’s goal. They are all unwillingly taken to Abilene.

- What ensues is anger and frustration. In response to the failure, the members grow indignant and dissatisfied with their organization. Consequently, they form micro-groups with selective acquaintances they trust and blame other micro-groups for the failure. Higher authorities aren’t spared from this either.

- If the issue at hand isn’t immediately resolved, the self-destructive cycle of decisions might repeat itself, bringing greater and greater devastation with each iteration.

The Solution

The psychology of all the members mentioned in the article seems reasonable: why waste energy debating when we’ve already arrived at an agreement? However, we have realized that it is not convenience but the fundamental urge to conform and the fear of exclusion that drive them to their failure.

We also know that conformity deters innovation and creativity. If James Joyce and Marcel Proust hadn’t deviated from the mechanical or overused plots of old literary fiction, we would have never experienced the fresh, relatable and highly analytical or philosophical plots of modern fiction. The same goes for the absurd representations of Picasso and the groundbreaking products from Google and Apple Inc.

The paradox can only be avoided if we create an environment that recognizes the confinements of conformity and allows for the expression of ideas, and grants people power to confront ideas without any threat to their jobs or identity. Confronting your anxiety and sharing your views, rather than hiding behind excuses and blame, is what rescues us from the snare of this paradox and provides us psychological relief. The ability to exercise the freedom of expression and confrontation, irrespective of his or her position in the organization, will discourage group tyranny and anti-social behavior.

Furthermore, the members must not rely on the hierarchy of authority to solve the problem; instead, each and every individual must bear an equal share of pressure and responsibility. Harvey repeatedly insists that members aware of the impending doom can save the organization by confronting, say, their president, but this might mean a non-refundable loss of not only just money, but also time and labor. However, a major loss is still better than a complete loss. Remember, it’s never too late to start all over again.