Table of Contents (click to expand)

Our internal voice was heavily linked to our ability to speak aloud. Inner speech was the internalization of external speech. Internal speech seems to rely on a system primarily involved in processing external speech, while the auditory content is provided by the corollary discharge.

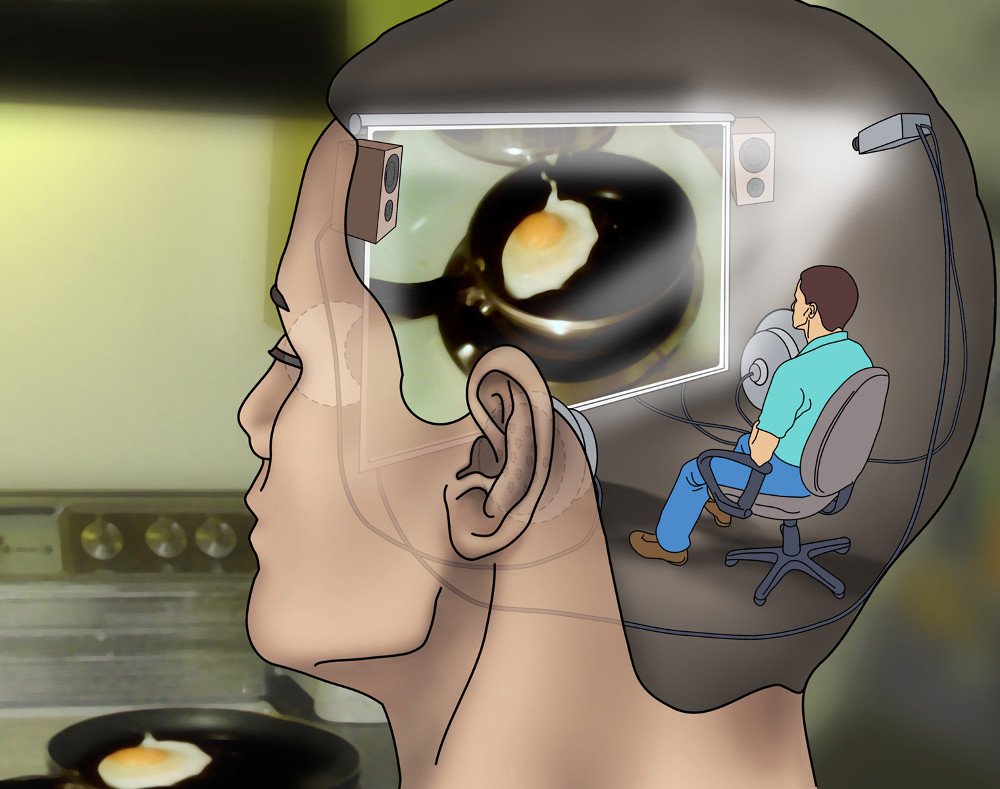

According to the Homunculus Argument, our brain is inhabited by an even smaller version of us, a homunculus, who interprets our external reality as the light from our surrounding falls onto him through our eyes. The theory is also popularly known as the theory of the Cartesian theater, because the framework of the mind that the theory draws is analogous to a man watching a series of images on a movie screen. So, is this the same guy responsible for that “little voice” in our head?

Obviously, the argument is a fallacy. The human brain doesn’t house a smaller version of you who cheerfully chomps on popcorn and sips on a can of coke every time you do something embarrassing. Instead, it’s an extremely complex biological organ made up billions of neurons, intricately connected to each other.

In lieu of its complexity, the brain can be divided into several parts. These parts can be isolated and held responsible for certain functions. Similarly, the inner voice can also be attributed to a single part or multiple portions working in harmony.

Recommended Video for you:

What Is Inner Speech?

Conventional wisdom tells us this is our conscience speaking, popularly depicted in the media as introspective dialogues with our angels and demons whispering in either ear. As you might have guessed, this also isn’t true. In psychological jargon, the voice you hear inside your head is called “inner speech”.

We use it every day, when going through shopping lists or motivating ourselves to finish that last slice of pizza. In fact, you’re probably using it right now to read this!

Inner speech allows us to narrate our own lives, as though it is an internal monologue, an entire conversation with oneself. We use it to to simulate past conversations and to imagine new ones. Since the emergence of psychology, there has been a strong effort to form a theory of mind. Inner speech has been of immense interest due to its contribution to motivational thinking and ubiquity in self-reflection. So how does it work?

Inner Speech As Internalized Outer Speech

In the 1930s, Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky suggested that our internal voice was heavily linked to our ability to speak aloud. According to him, inner speech was the internalization of external speech. This implies that inner speech should activate the same organs that external speech does. This is certainly true. Electromyography, a technique to measure the movement of muscles, shows that the larynx is activated during inner speech.

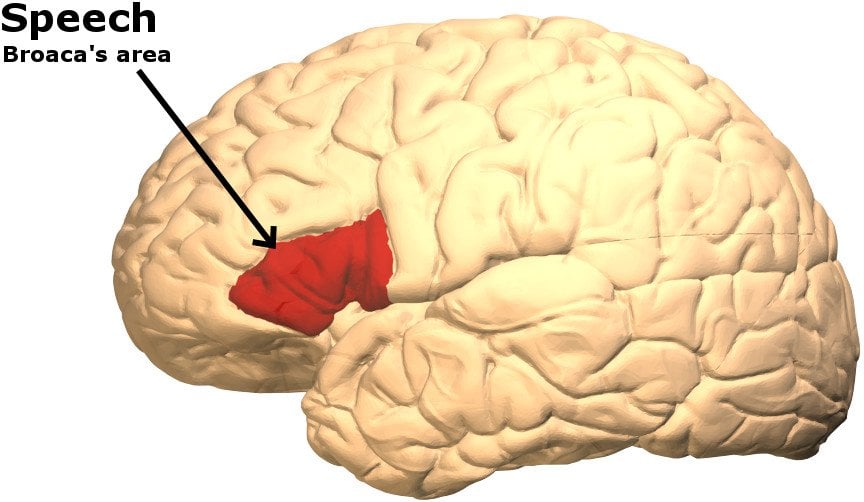

His claims were cemented when neuro-imaging of individuals indulging in inner speech highlighted certain parts of the Broca’s area — a part of our brain residing in the left hemisphere, described by its discoverer, physician Paul Broca, to be “the faculty of language.” Add to that the disruption of both outer and inner speech when the responsible parts in the Broca’s region are disturbed with stimulating techniques.

People often report that their inner speech occurs at a much faster rate than it would be physically possible to speak aloud. One reason could be the neglect for grammatical mistakes, as you almost always know what you mean, making the articulation of sentences much swifter.

Corollary Discharge

Another key finding was the activation of corollary discharge — a neural signal that helps us distinguish between self-generated sensory experience and externally produced sensory experience.

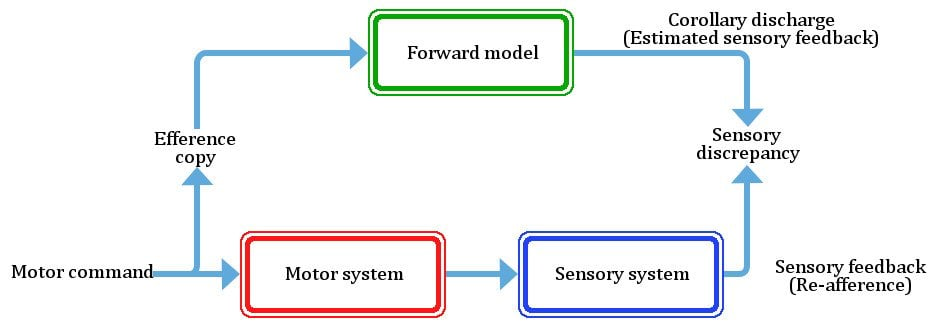

When an animal performs a task, its motor system uses a forward model or an internal model of the body to predict the sensory consequences upon its completion. This neuronal activity providing us with a vague prediction is the result of corollary discharge.

The study was conducted by Mark Scott, a university researcher in British Columbia, and suggests that during speech, the brain generates an internal copy of the sound of our voice in parallel to the external sound we hear. If the internal sound is not cancelled out or recognized with respect to external ones, we’d be really confused and communication would be chaotic.

He hypothesized that if corollary discharge predicts our own movements and prevents the confusion between self-caused and externally-caused sensations, then sensory information coming from the outside world should be cancelled out by the internal copy produced by our brains if the two sets of information match. This is why tickling yourself is ineffective.

This is exactly what the data shows: the impact of external sound is reduced when participants say a syllable in their heads that matched the incoming external sound. Thus, internal speech seems to rely on a system primarily involved in processing external speech, while the auditory content is provided by the corollary discharge.

“You Should Get That Checked Out.”

This article may come as a surprise for people who are alien to this ability, and their reaction might come across as a surprise to people who invoke it everyday! Yes, inner speech is not a universal phenomenon. It’s varied amongst individuals. Its possessors, including me, are convinced of its normality, but it is far from being normal. In fact, people who claim that they did not have inner speech felt that they were “normal”!

For instance, in response to a question posted on Yahoo answers about whether anyone else hears themselves while reading, responders exclaimed “Nooo! You should get that checked out,” whereas one responder bluntly commented in all capitals: “NO, I’M NOT A FREAK.”

Why Is It Important?

Other than mere fascination, psychologists and neurologists have long studied inner speech because it can provide them with major insights regarding auditory hallucinations — hearing voices in the absence of any external stimuli. Experts believe that auditory hallucinations can be the result of our inability to recognize inner speech as self-produced.

Part of Scott’s research to discover the mechanisms of inner speech was intended to find a solution to mitigate such mental afflictions. However, studying the ways people talk to themselves in their minds is exceedingly tricky, because it’s counteractive in nature. The delicacy and sensitivity of our stream of consciousness does not permit it to be studied without being affected at the same time — any attempt to dissect it is simultaneously an act of fiddling with it.

References (click to expand)

- You hear a voice in your head when you’re reading, right? – Research Digest - digest.bps.org.uk

- Raij, T. T., & Riekki, T. J. J. (2012). Poor supplementary motor area activation differentiates auditory verbal hallucination from imagining the hallucination. NeuroImage: Clinical. Elsevier BV.

- Scott, M. (2013, July 11). Corollary Discharge Provides the Sensory Content of Inner Speech. Psychological Science. SAGE Publications.

- Scott, M., & Gick, B. (2012). Corollary discharge and context effects. Proceedings of Meetings on Acoustics. Acoustical Society of America.