Table of Contents (click to expand)

Cigarettes are so addictive because they contain nicotine, which is a physical addiction. Nicotine causes the body to release dopamine, which is a neurotransmitter associated with euphoria. Cigarettes also stimulate other sites responsible for relaxation.

Derek Parfit, in his moral philosophy masterpiece Reasons and Persons, describes the Self-interest theory, a theory about rationality stating that we must fulfill only those desires that cause our lives to go as well as possible. Later, Parfit presents a moral dilemma where an artist whose strongest desire is to produce a reverential piece of art can only achieve that goal if it comes at the cost of isolation from her loved ones and, consequently, her wellbeing. Emily Dickinson was one such revered poet who, for the sake of her work, preferred isolation and solitude. Is this desire rational?

It is, according to a branch of the Self-interest theory – the Desire Fulfillment Theory – which prioritizes the fulfillment of strong desires, despite the scourge it may represent in our lives. Skimming through my copy of Reasons and Persons, I could only think of one desire that conformed to the Desire Fulfillment Theory and would require what Parfit calls an irrational act of rationality – addiction. It is rational only in the personal sense that its fulfillment allows the addict to wallow in a rush of contentment, however ephemeral. It is irrational because this desire’s fulfillment will simultaneously, albeit slowly, kill him.

Smoking, or the consumption of tobacco, is reported to be the most addictive amongst all addictions; even cocaine fails to compete. A study revealed that while cocaine users managed to quit at Year 4, dependent smokers struggled to put down the cigarettes even after 30 years!

The quest for the next fix deprives an addict’s family of income, increases health costs and decreases economic development. Each year, more than 7 million deaths are related to smoking. While 6 million deaths are caused by first-hand abuse, 890,000 deaths are the unfortunate passive or second-hand smokers.

A box of cigarettes is essentially a scabbard for the most dangerous weapon in the world, but its wounds are self-inflicted. What is so compelling about them that, for momentary pleasures, one voluntarily and gradually pulls down on his own guillotine?

Recommended Video for you:

Nicotine

Nicotine is an alkaloid, a nitrogen-containing compound that is secreted by the tobacco plant. Nicotine is known to be physically addictive, which means that its deprivation induces physical discomfort in regular users. When a smoker relishes a cigarette, the nicotine swims through his blood toward the various neurological receptors in his brain. Upon being stimulated, the receptors emanate neurotransmitters. These are chemical messengers stored in cisterns called vesicles, which are attached to the end of neurons.

One influential neurotransmitter released following the consumption of nicotine is acetylcholine. It is responsible for focus, aloofness and rejuvenating consciousness itself, provoking the feeling of “being in the moment”. Any substance that inspires such a stimulating experience and, to some extent, enhances cognition, is known as a stimulant.

The Cycle Of Craving

When a receptor receives a certain signal, it releases the contents of its vesicles into its synapse, which relays them to the adjacent neuron. A pathway is created. Neurotransmitters can be reabsorbed by a process called reuptake, a process that permits the acute regulation of transmitters in a synapse.

The introduction of a substance, stimulant or depressant, enacts a sharp needle that bursts open a vesicle to release a gush of transmitters. This disrupts the balance, rendering the consumer with an altered behavior – the inability to cope with addiction.

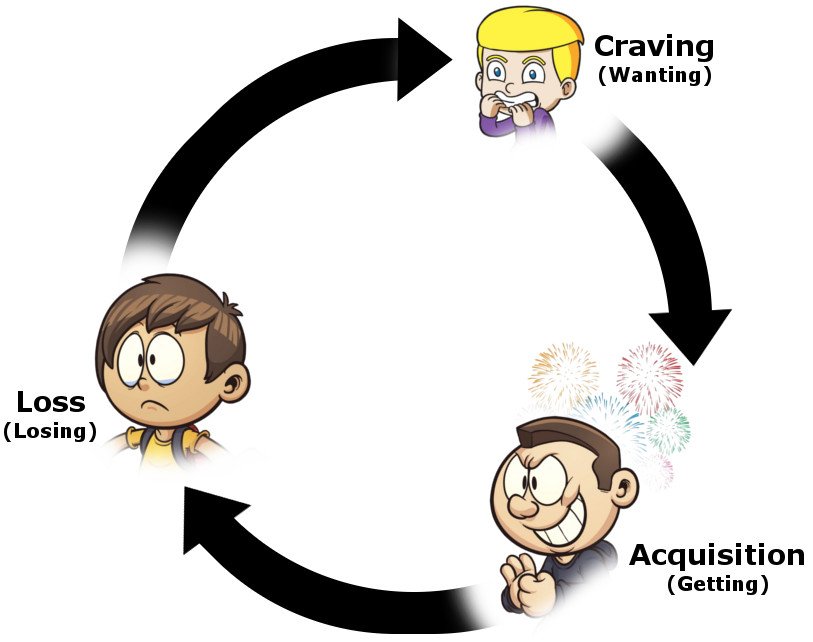

Like a hamster hopelessly stuck in his wheel, an addict is plunged into a vicious cycle – a cycle of craving. The cycle starts with the emergence of a desire or craving, leading to the acquisition of the substance and, finally, after savoring it, its eventual loss.

Each time an addict goes through the cycle of wanting, getting and losing, a neuronal pathway corresponding to this goal is enriched. Subsequently, as this pathway becomes increasingly strong, neglected pathways that correspond to other goals become futile.

Cravings are so nail-bitingly compelling because desires cannot be so easily dismissed, particularly primitive desires that are, in evolutionary terms, crucial for survival, such as pleasure. They stem from the darkest and most remote corners of our minds, the part of our mind that we call the reptilian brain.

Also, cravings are not necessarily fueled by substance abuse; they are quite ubiquitous in our daily lives. Love is one example where withdrawal, as in the case of tobacco, leads to severe anxiety or distress. Neurologist Marc Lewis cites the example of watching our team get the ball to depict the fulfillment of a craving.

Furthermore, cravings are also triggered by contextual cues, such as the smell of tobacco, or the onset of certain moods and environmental cues, such as visiting the café where you smoke every evening. The habit of smoking is like any other habit, it is structured on a learning process that links contexts, be it place or time, to an act.

Negative Rewards

Nicotine also facilitates the production of dopamine, the neurotransmitter conventionally associated with euphoria. However, dopamine is actually linked to promoting the pursuit of a desire or goal. A wave of dopamine bathes our receptors each time we fulfill a desire. Nicotine stimulates several other sites responsible for arousal, as well as relaxation.

When I say that dopamine is released when our pursuit of a goal or desire is successful, the goal could either be solving an intellectual puzzle or munching on an eclair. The point is, it makes us feel good, as if a reward for fulfilling the desire. A cigarette, however, lets you cheat. A smoker can claim the reward without the hard work.

This is also why cravings are triggered by an absence of a stimulus, such as during a bout of boredom. And why wouldn’t they? I mean, however undeserved, who would refuse a tantalizing reward or a stolen pleasure? A free lunch! Of course, these rewards are not entirely free, as the short-term pleasure has a long-term consequence. They are enjoyed at the price of your life, but for the time being, the void has been filled.

This is particularly lucrative in cases when we wish to get rid of our anxiety or irritability immediately. This expediently gained reward is known as a negative reward. Abuse then appears to be a coping mechanism, an act of seeking pleasure and comfort in a world that does not cooperate.

However, not everyone welcomed the habit so that they could blow dense smoke in the face of adversity to hide and pretend that it was never there. Some people succumb to peer pressure, social acceptance or encouraged by its glorification in film culture, take it up because it looks cool.

What these people don’t realize is that smoking, like drinking coffee, is essentially an act of borrowing happiness from the future. To make up for which, one must borrow again and again and again. What starts out as fun soon turns into a cycle of dependence, pedaled by desperation.

So, why are cigarettes the hardest to kick?

Other than the deep neurological mechanisms I mentioned, social or economic factors also come into play. First of all, cigarettes are very cheap. Second, unlike hard drugs, they aren’t stigmatized. Like alcohol, cigarettes are legal and sold everywhere, but most importantly, they are socially accepted. Considering these two, acquisition isn’t a big deal.

Third, the kick is right on the money. Unlike hard drugs, it is neither too much to hinder your daily life, nor too little to make you feel betrayed. Oscar Wilde didn’t even need the help of neurology to figure this out when he remarked: “A cigarette is the perfect type of a perfect pleasure. It is exquisite, and it leaves one unsatisfied. What more can one want?”

References (click to expand)

- Tobacco - World Health Organization (WHO). The World Health Organization

- Heyman, G. M. (2013, March 28). Quitting Drugs: Quantitative and Qualitative Features. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. Annual Reviews.

- Markou, A. (2008, July 18). Neurobiology of nicotine dependence. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. The Royal Society.

- So Hard To Quit: New Mechanism in Nicotine Addiction .... neurosciencenews.com