Table of Contents (click to expand)

While the precise causes are unknown, factors like social and religious stress, mass psychogenic illness, and even ergot poisoning have been suggested.

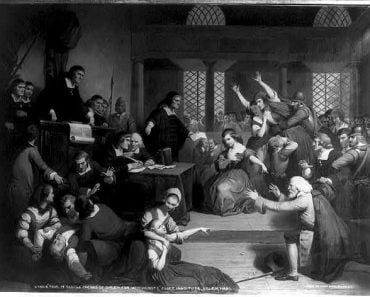

Amid the flickering torchlight of a medieval village square, a scene of dance hysteria unfolds, captivating the senses and defying rationality. The night air is thick with tension, and a palpable sense of otherworldly fervor pervades the gathering. A diverse group of villagers has congregated, their faces etched with a mix of awe, fear, and exhilaration.

Men, women, and children are all swept up in a mesmerizing dance. They wear tattered and mud-splattered clothes. Some clutch rosary beads, while others raise their hands towards the heavens, as though seeking divine intervention.

The phenomenon of “dancing mania” or the “dancing plague” that swept across Europe during the Middle Ages, particularly during the 14th to 17th centuries, remains a subject of historical fascination and debate. These episodes of mass hysteria, where individuals would compulsively dance for hours or days without apparent control, continue to captivate the imagination.

While there isn’t a single definitive explanation for these occurrences, several factors likely contributed to these episodes, deeply rooted in the social, religious, environmental and psychological landscape of the time.

Recommended Video for you:

Social And Religious Stress

The Middle Ages were a tumultuous period characterized by significant social and religious stress. Plagues, famines, and wars were widespread, causing immense suffering and uncertainty. People, grappling with the harsh realities of their era, often turned to religion for solace. In this context, dancing could be viewed as a form of worship or penance.

During times of crisis, communal rituals, including dance, offered a means of coping with the profound anxieties of the era. Dancing became a way to seek solace, forgiveness, and connection with the divine. It was a physical manifestation of collective grief and a desperate plea for divine intervention.

Gender, class, and age may have also played a role in the dynamics of this dancing mania. Some outbreaks were predominantly among young women, while others involved people from various demographics. The specific demographic composition of the affected populations could have influenced the dynamics and interpretation of dancing mania. It’s essential to consider how societal norms and expectations shaped the experiences of those involved, as well as those who observed and recorded this phenomenon.

Some outbreaks of dancing mania were intimately linked to religious fervor. In the medieval mindset, intense physical experiences were often seen as a means of seeking divine favor or purging one’s sins. Participants may have genuinely believed that their frenzied dancing was a way to achieve spiritual purification and find redemption.

Dancing fervently was believed to be a form of devotion that could expel evil spirits and invite divine intervention. Conversely, it could be a sign of demonic possession or evil, eliciting a mass frenzy that may have exacerbated the conditions.

Mass Hysteria

Dance was an integral part of medieval culture. Many festivals, celebrations, and religious ceremonies involved dancing. It’s possible that in certain circumstances, an enthusiastic and communal dancing experience escalated beyond control. The social acceptance and normalization of dance provided a backdrop against which dancing mania could unfold.

Once the dancing began, it often spread like wildfire, captivating entire communities. The power of suggestion and collective hysteria played a significant role. Mass psychogenic illness, where a group of people experiences physical symptoms due to psychological factors, might explain some instances of dancing mania. Witnessing others dancing uncontrollably could have triggered a psychological response in susceptible individuals, leading them to join in the frenzy. In this way, mass hysteria perpetuated the phenomenon, creating a self-sustaining cycle.

The act of dancing became a collective expression of discontent or a brief reprieve from the harsh realities of their existence.

Ergot Poisoning

One intriguing theory suggests that contaminated rye bread may have contributed to outbreaks of dancing mania. Rye grain can become infected with the fungus Claviceps purpurea, which produces ergot alkaloids. Consumption of these alkaloids can lead to hallucinations, muscle spasms, and a sensation of burning. Ergot poisoning might have caused people to dance uncontrollably. However, this theory remains debated, as ergotism’s symptoms differ from the typical behaviors associated with dancing mania.

Nevertheless, while mass hysteria and cultural factors likely played a significant role, there might have been instances where underlying medical conditions, such as epilepsy or encephalitis, contributed to some individuals’ erratic behavior, which then influenced the group. The interplay between psychological and physiological factors further complicates our understanding of dancing mania.

Conclusion

In essence, dancing mania was a complex phenomenon with multifaceted causes deeply intertwined with the socio-religious fabric of medieval Europe. The specific factors at play likely varied from one outbreak to another, making it challenging to pinpoint a single cause. Furthermore, our understanding of these events is limited by the historical records available, which were often influenced by the biases and interpretations of the clergy and authorities.

Moreover, dancing mania offers a unique window into the psychological responses of communities facing extreme stress and uncertainty. It highlights the power of collective behavior and the role of cultural, religious, and social factors in shaping human responses to crises. While the dancing mania of the Middle Ages may never be fully explained, it continues to serve as a compelling historical and psychological enigma, inviting further exploration and interpretation.

This phenomenon underscores the human capacity to express and cope with distress through communal rituals and provides insight into the complex interplay of social, psychological, and cultural factors during times of adversity. Dancing mania remains a testament to the enduring mysteries of history and the bizarre nuances of the human condition.

References (click to expand)

- Dickason, K. (2021, January 21). Dance in the Late Middle Ages. Ringleaders of Redemption. Oxford University Press.

- Gotman, K. (2017). Translatio. Oxford Scholarship Online. Oxford University Press.

- RE BARTHOLOMEW. (2000) Rethinking the Dancing Mania.

- Bartholomew, R. (1998, May). Dancing with Myths: The Misogynist Construction of Dancing Mania. Feminism & Psychology. SAGE Publications.

- Bartholomew, R. E. (1994, May). Tarantism, dancing mania and demonopathy: the anthro-political aspects of ‘mass psychogenic illness’. Psychological Medicine. Cambridge University Press (CUP).