Table of Contents (click to expand)

There appear to be differences between the brains of good and bad navigators, but you can develop your sense of direction, much like any other skill. Reducing how much you rely on GPS services, and becoming more confident in your unaided abilities, may help improve your sense of direction.

If you’ve ever gone on a camping trip with friends and felt doomed to get lost without your ‘super-navigator’ friend, don’t worry, you’re not alone. I am often ridiculed for having zero sense of direction. It’s a nightmare to navigate new surroundings.

For some, their sense of direction can be so bad that they need to use GPS to visit their favorite shop, even if it’s right around the corner. For others, the only time they get confused is when they try to find their way to an unfamiliar place at night.

If thousands of people feel this way, what makes our super-navigator friends so special?

To answer this question, we need to delve into the biology of navigation.

Recommended Video for you:

Why Are Some Of Us Terrible At Navigating Properly?

Not being able to find our way home is a genuine fear for many of us, but with the help of trusty friends and gadgets, we manage to travel around the world.

However, there are some people for whom this lack of ability is a genuine nightmare. People with developmental topographic disorientation conditions have a much harder time gauging directions than your average person. Their inability to orient themselves in their environment can be so debilitating that some even get lost inside their own homes.

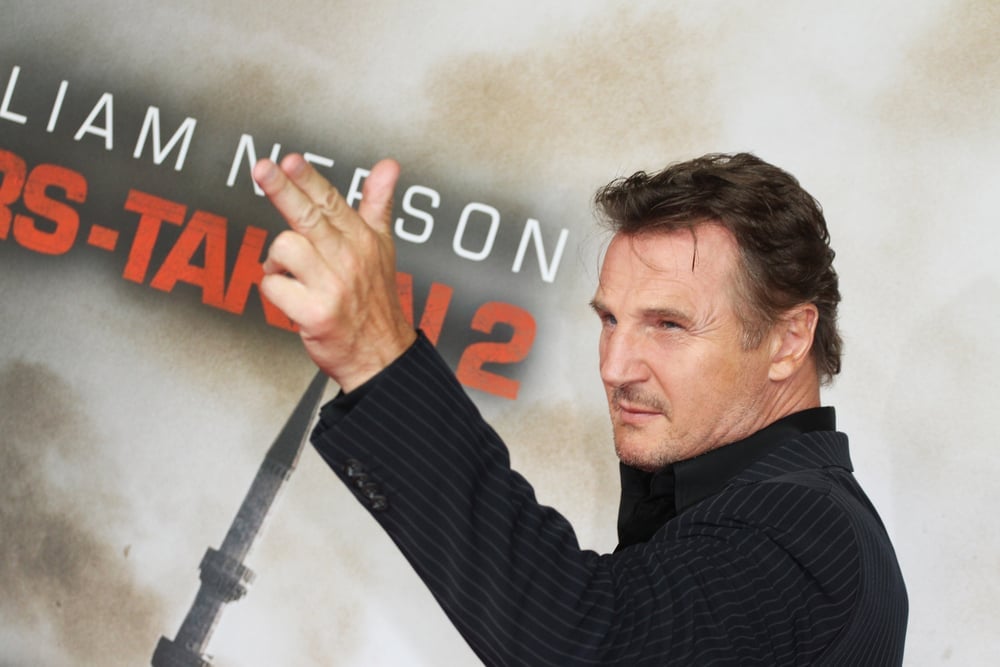

While this condition is the extreme version of poor directional sense, most of us would still struggle to be as good as Bryan Mills (played by Liam Neeson) in the Taken series and successfully find our missing loved one, especially while blindfolded in the back of a car. In order to understand what we lack that Bryan might have (other than the magic of Hollywood), we need to understand where our sense of direction comes from.

Your Sense Of Direction

Our directional sense actually results from a multitude of several senses and brain cells interacting together. In addition to the primary five senses, particularly sight and hearing, we also use proprioception and the vestibular system to help us better comprehend the world.

Proprioception tells us where we are in relation to our environment, while the vestibular system in our ears helps us balance and orient ourselves in a given space.

All these tools help us go where we want without bumping into every pole or getting dizzy every time we try to orient ourselves in a moving world.

Additionally, high anxiety levels and low self-confidence could also play a role in our directional abilities. If someone repeatedly tells you that you’re the world’s worst navigator, it starts to become a self-fulfilling prophecy, as you may start believing those words too.

There are several other reasons why we might end up like Columbus and accidentally end up in America, rather than India. One such reason could be our extreme reliance on GPS technology. Roger McKinlay says in a Nature article that “[…] navigation is a ‘use-it-or-lose-it’ skill”. Since navigating requires you to pay attention to your surroundings, memorize landmarks and construct mental maps, not using those skills will often weaken your spatial knowledge and capabilities.

Thus, it seems like switching off our GPS might be the best method to improve our directional sense.

However, just like everything else, this story is far more complex than that.

Scientists report that there could also be biological differences that enable certain people to be better navigators.

What Happens Inside The Brain Of A Navigator?

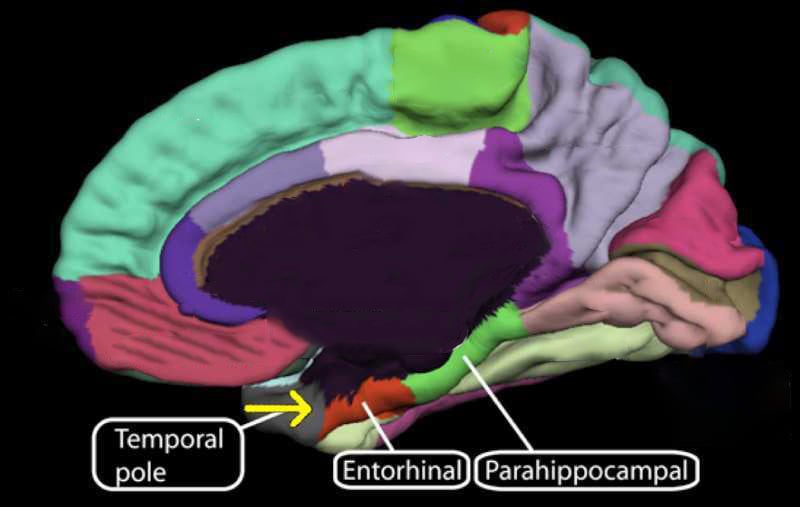

A specialized region in our brain called the entorhinal cortex is responsible for our sense of direction. You might recognize the name of the more famous structure associated with memory, the hippocampus. The entorhinal cortex is located adjacent to this structure.

These structures house three primary types of cells with specific functions that relate to our spatial cognition. Research is still ongoing and continues to evolve, so you can read more about the different types of navigation cells in the review article published in Current Biology.

Place Cells

Nobel Prize winner John O’Keefe discovered these cells in the hippocampus (associated with memory) that help guide us within the world. O’Keefe and his colleagues describe a collection of cells termed “place cells” that help in identify one’s place in an environment.

Grid Cells

These cells in the entorhinal cortex help construct a map of where you have recently been and coordinate with the “place cells” to figure out where you are and how to get back to where you started.

Head-direction Cells

These unique cells in the entorhinal cortex are thought to act like a compass. They fire anytime we face a particular direction, such as turning east to see a tall building or a prominent geographical feature.

If we all have this region, why are some people better at navigating than others?

This can potentially be explained by normal brain variations among people. Human development is an intimately delicate process, and even the slightest variation in signaling events can have profound implications on neurological development.

A study by O’Keefe and his colleagues showed that the directional cells in rats are present very early on in life. Some of these cells were already at their adult stage in newborn rats. This indicates that at least some part of our directional sense might be innate.

The good news is that this ability can improve as life goes on since environmental and lifestyle stimuli help shape our brains through neuroplasticity.

A study using brain scans showed that a difference in brain signaling strength in the entorhinal cortex could impact our directional sense.

That being said, it must be noted that brain activity scans don’t show the whole picture of what’s going on inside our heads. There is still a lot to learn, but we’re making our way closer.

A Final Word

Whether you’re a modern-day Lewis and Clark or hopelessly lost looking for the checkout area of your local supermarket, everyone has specialized cells that can help with their sense of direction. Although it seems like our super-navigator friends might have some biological advantages, more intense research is necessary before a definitive conclusion can be made.

For now, roaming around a bit without GPS might do the trick and help improve your sense of direction, though be sure to stay safe, especially if you’re driving!

Whatever your navigation skillset may be, the world still has a lot to learn about our brains and the way they work.

Until then, good luck and bon voyage!

References (click to expand)

- Burles, F., & Iaria, G. (2020, December 1). Behavioural and cognitive mechanisms of Developmental Topographical Disorientation. Scientific Reports. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Vestibular System and Proprioception: The Two Unknown .... Ochsner Medical Center

- Hund, A. M., & Minarik, J. L. (2006, September). Getting From Here to There: Spatial Anxiety, Wayfinding Strategies, Direction Type, and Wayfinding Efficiency. Spatial Cognition & Computation. Informa UK Limited.

- McKinlay, R. (2016, March 30). Technology: Use or lose our navigation skills. Nature. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Makin, S. (2015, April 9). The Brain's Homing Signal. Scientific American Mind. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Chadwick, M. J., Jolly, A. E. J., Amos, D. P., Hassabis, D., & Spiers, H. J. (2015, January). A Goal Direction Signal in the Human Entorhinal/Subicular Region. Current Biology. Elsevier BV.

- Wills, T. J., Cacucci, F., Burgess, N., & O'Keefe, J. (2010, June 18). Development of the Hippocampal Cognitive Map in Preweanling Rats. Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).