The “biological clock shift” keeps teenagers awake until late at night. This clock operates through a complex network of genes that are activated and deactivated in a specific sequence.

If you have a teenager at home and you think they’re being rebellious by ignoring your orders to go to bed at a reasonable hour, it’s likely a misunderstanding of their actions. The root cause of this behavior is as much biological as psychological or social.

Adolescence is a difficult time of life; the body and mind undergo major transformations during this phase, brought on by fluctuating hormones.

One change is that the circadian rhythm in teenagers naturally shifts, which means that their brains want to put teenagers to bed later than their adult-enforced bedtime.

Recommended Video for you:

The Body’s Internal Clock And The Sleep-wake Cycle

Organisms undergo rhythmic changes in their physical, mental, and behavioral states over a 24-hour cycle, known as circadian rhythms. The system that regulates these rhythms and an organism’s innate sense of time is called a biological clock.

In humans, almost every tissue and organ operates on its own biological clock. However, there’s a boss clock that calls the shots and is responsible for coordinating all these individual clocks, and that top-tier timekeeper resides in the brain.

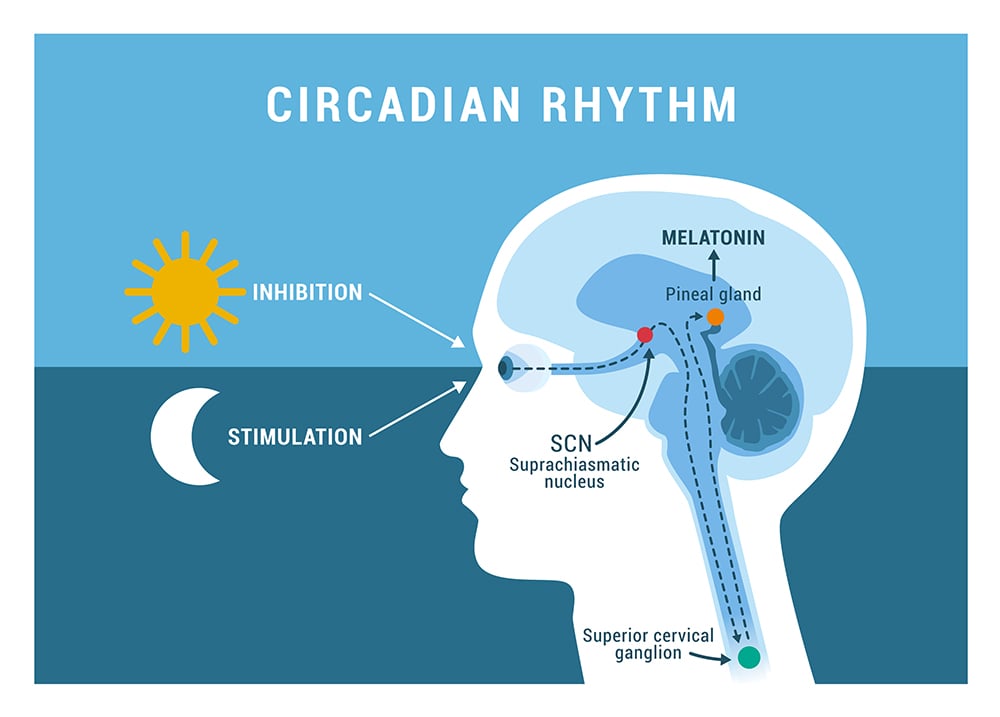

This master clock is a bunch of nerves that constitute a structure known as the suprachiasmatic nucleus or SCN, and it influences your sleep-wake cycle. Somewhere around puberty, the clock undergoes certain changes. It hits the reset button in a way that delays when you fall asleep and wake up. In simpler words, the clock gets nudged forward.

Sleep-wake Cycle In Teens Is Pushed Forward

This biological clock shift keeps teenagers awake until later at night. This clock operates through a complex network of genes that are activated and deactivated in a specific sequence.

A critical function of this clock involves regulating the sleep-wake cycle by controlling the production of melatonin, a hormone influenced by the amount of light perceived by the eyes. In the evening, the clock signals the brain to increase melatonin production, inducing sleepiness. However, in teenagers, melatonin release is delayed, prolonging the time it takes to fall asleep.

Many factors can influence the clock’s function: light and darkness, social environment, stress, temperature, and physical activity. Research indicates that gonadal hormones, which fluctuate during puberty, can affect the circadian rhythm. This phenomenon is not exclusive to humans; other animals, such as rodents and monkeys, also experience a delay in circadian rhythms around puberty, partially due to changes in their gonadal hormones.

Effect Of Hormonal Shifts On Circadian Rhythms

In studies with rodents, researchers found that giving hormones like estrogen, progesterone, testosterone, and other neuroactive steroids immediately affected their sleep patterns and daily rhythms. The same thing happened when the animals had their gonads removed.

Scientists think that sex hormones can shake things up in the brain’s suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), causing it to work differently. They also noticed changes in the SCN’s structure in rats around the middle of puberty.

Further evidence of how gonadal hormones impact circadian rhythms can be seen in the changes in sleep during the menstrual phase in females.

Research finds that during the luteal phase, the part of the menstrual cycle right before menstruation kicks in, our bodies release less melatonin and cortisol than during other phases. Despite sticking to their regular sleep schedules, many women report their worst nights of sleep during this time.

While gonadal hormones are necessary for shifting the body clock in some animal species, they only partly influence the sleep cycle in others. It seems that during puberty, other physiological changes may also contribute to disruptions in the sleep-wake cycle. However, these additional changes remain unclear and require further exploration.

Adolescent Behavior And Sleep Cycle

When it comes to adolescent behavior and sleep, digital devices play a key role.

The light from screens like TVs, smartphones, and gaming stations can delay melatonin release and interrupt the sleep cycle.

The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) is hooked to the retina and connected to the pineal gland, which releases melatonin. So, when light hits the retina, that signal travels to the SCN and eventually reaches the pineal gland.

This means that light, and therefore darkness, can rather easily disrupt melatonin release.

A Final Word For Parents

Sleep deprivation is no joke for teenagers, as it can be a leading cause of several health issues. Research shows that messing with their circadian rhythms can cause an increase in reward-seeking behaviors and a reduction in cognitive control. It therefore leaves sleep-deprived teens more vulnerable to addiction and substance abuse.

So, no matter how frustrating it may be to deal with your constantly drowsy and perpetually tired teenager, it’s crucial to remember that they genuinely need your care and patience. It’s important to recognize that their behavior isn’t a result of arrogance or disrespect, rather that their bodies are going through significant developmental changes that require the right amount of patience and understanding on your part.

References (click to expand)

- ◂ - sci-hub.se

- Circadian Rhythms.

- Department Faculty Highlight the Role of Adolescent Sleep ....

- Carskadon, M. A., Acebo, C., Richardson, G. S., Tate, B. A., & Seifer, R. (1997, June). An Approach to Studying Circadian Rhythms of Adolescent Humans. Journal of Biological Rhythms. SAGE Publications.

- Baker, F. C., & Driver, H. S. (2007, September). Circadian rhythms, sleep, and the menstrual cycle. Sleep Medicine. Elsevier BV.

- Hagenauer, M. H., Perryman, J. I., Lee, T. M., & Carskadon, M. A. (2009). Adolescent Changes in the Homeostatic and Circadian Regulation of Sleep. Developmental Neuroscience. S. Karger AG.

- Explainer: The teenage body clock.