Table of Contents (click to expand)

The feeling of nervousness is a natural consequence of our hard wired fight and flight response. Nervousness is caused by the primitive parts of the brain, which are hardwired to respond to threats. The feeling of nervousness is a result of the sympathetic nervous system sending out impulses to glands and smooth muscles, and the adrenal medulla releasing adrenaline and noradrenaline into the bloodstream.

Why do I get nervous? The answer is that feeling nervous is a natural consequence of our hard wired fight and flight response! The butterflies in your stomach occur as blood from digestive system is redirected.

An extremely important exam or presentation, getting married, starting a new job, proposing to your girlfriend/boyfriend, expecting a baby, the illness of a parent… these various life events all have something in common. Apart from the fact that they are normal parts of life, all these incidents invoke certain emotions, and one that is common to all major life events is the feeling of nervousness.

Nervousness seems like that old grumpy uncle at a wedding whose presence can be ignored, but it affects the mood nonetheless. That may be a bad analogy, but nervousness does seem to bring us down, regardless of the exterior circumstances, often making a happy event much less enjoyable, or a tense moment, such as an exam, even worse. If it’s so detrimental to us, then why have we developed this response over thousands of generations? Shouldn’t evolution be taking care of this stuff?

Well, the answer is that evolution knows better than us, and is taking care of you by making you nervous. Don’t believe me? Let’s take a look at why we get nervous in high-pressure situations, and perhaps you’ll begin to understand.

Recommended Video for you:

Role Of The Primitive Brain

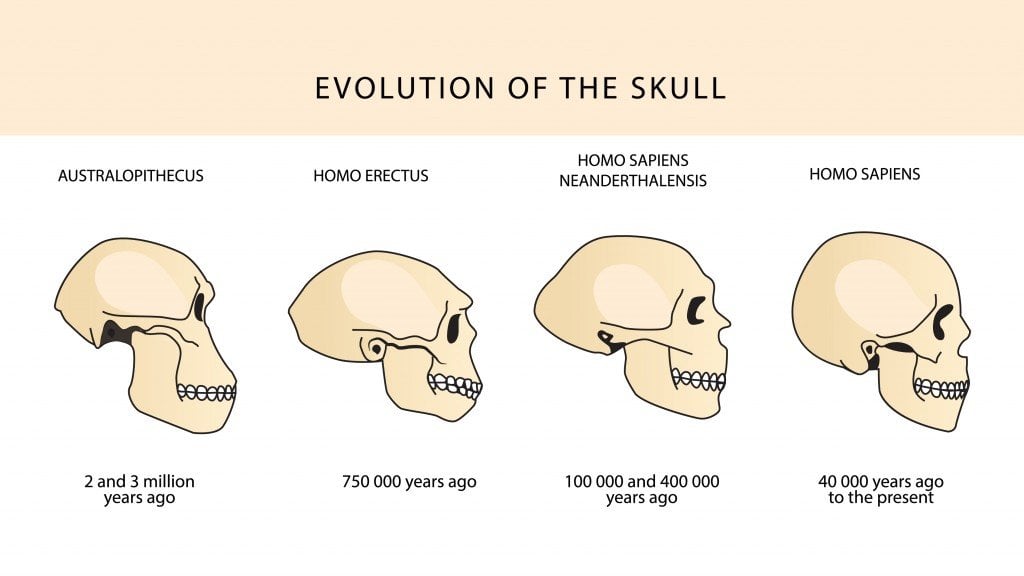

The human brain has evolved very slowly over millions of years to become the brain it is today. Evolutionary biologists believe that the most primitive parts of the brain evolved over 500 million years ago and included only the brainstem and spinal cord. However, the limbic system, which forms a part of the midbrain, developed 200-300 million years ago, long before the cerebrum or neocortex. So, whatever functions it performed back then is hardwired within us to this day.

The limbic system performs several critical functions, such as regulating blood pressure, heart rate, body temperature, and blood sugar levels, in addition to maintaining homeostasis, sexual arousal, memory, learning, and even the fight or flight response. It performs all these functions by influencing the autonomic nervous and endocrine systems. The response of interest here is fight and flight, which is regulated by a part of the autonomic nervous system called the sympathetic nervous system, and another called the adrenal-cortical system. In the past, when primitive man perceived a threat or danger, such as a wild animal approaching, this system of the brain was activated, which prepared the body either to fight (if the animal was weaker) or flee (if it was stronger) in order to survive. Both these actions require energy and blood to be directed to your muscles that will enhance their functioning.

Fight Or Flight

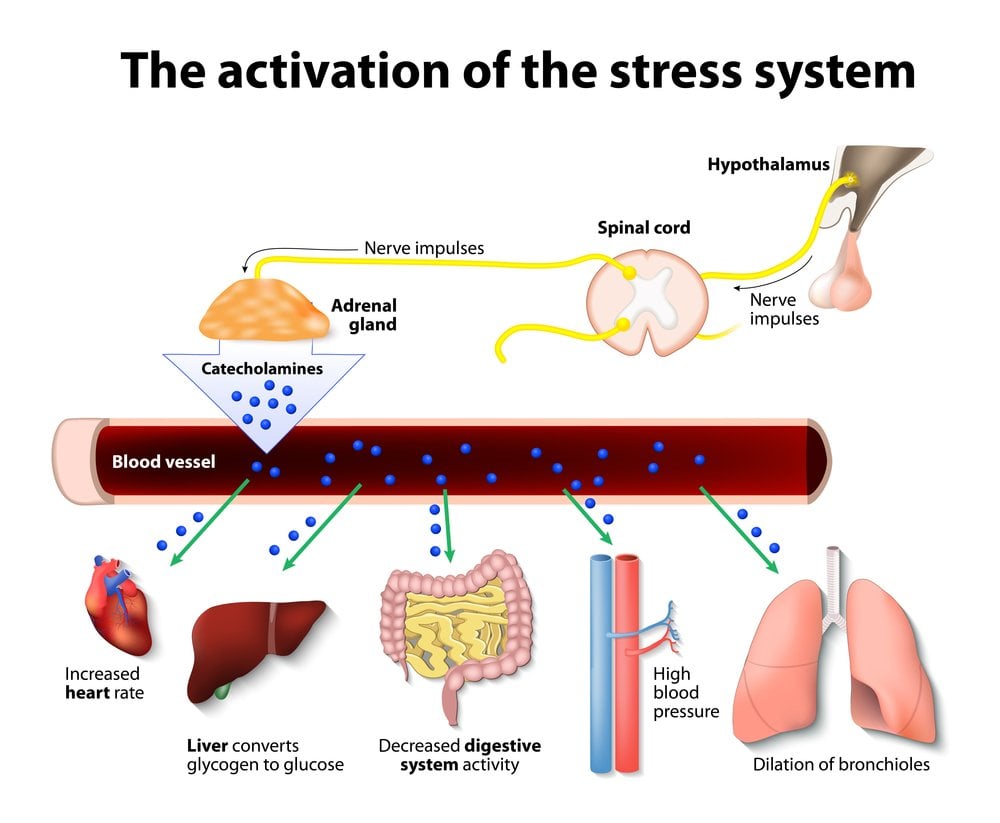

When your neocortex (in essence, you) attaches extreme importance to an activity, such as those mentioned above, it triggers a part of the limbic brain called the hypothalamus and the signal is misperceived, as though there is some sort of danger, since your situation is not considered “normal” in your brain. The hypothalamus thus triggers the fight or flight response, in which the sympathetic nervous system sends out impulses to glands and smooth muscles, and directs the adrenal medulla to release adrenaline and noradrenaline into the bloodstream, which increases heart rate and blood pressure.

Simultaneously, the hypothalamus also releases corticotropin-releasing factor into the pituitary gland, which triggers the adrenal-cortical and leads to the release of several hormones. In this manner, your brain sends a signal to the kidneys, where the adrenal gland is situated. The gland releases a hormone called adrenaline, which helps to redirect blood and energy to those parts of the body that will be required to take rapid action, such as the heart and muscles and away from not so important processes, such as digestion. Since the blood flow is directed away, the blood vessels around the stomach close, which may cause the tingling sensation (butterflies in your stomach), which we commonly attach to being nervous.

The misinterpretation happens because the response has been hardwired for a million years, even before your rational, conscious decision-making brain developed. So, the fight or flight response for an exam may lessen slightly every few centuries or so, as our conscious brain learns to override our primitive one, but it’s not happening anytime soon.

Have you noticed that once you start feeling nervous, it’s very difficult to get back to your pre-anxious state? This is because as soon as you think you’re feeling nervous, your brain once again receives a signal concerning some sort of threat, so it continues to stimulate that fight or fight response until the threatening situation is over.

However, some people feel nervous/anxious even in low-pressure daily situations or without recognizable triggers. In psychological terms, these people are thought to be trait anxious, i.e., they may have lower thresholds than the majority of the population for situations that they consider stressful. Being perpetually nervous could also be a precursor of an anxiety disorder.

The good news is that there are hordes of simple methods or exercises to control your nervous feelings, irrespective of whether you are situationally nervous, trait anxious, or suffering from an anxiety disorder, so that they don’t overwhelm you.