Table of Contents (click to expand)

Many studies suggest that the large amounts of testosterone in the body stimulates fast and rapid growth facial hair. As the girls have more estrogen than testosterone, their facial hair growth is not prolific.

Take a second to think about how human hair grows. Then compare it with any other mammal. You’ll be hard pressed to find any other animal (keeping marine mammals like whales and dolphins out of the picture) that grows long luscious hair on selective parts of their body (head and, for men, chin and cheeks), and sparse growth in others (like the arms, legs, abdomen). And by extension, why do humans, especially females, practice hair removal?

Recommended Video for you:

The Role Of Hormones In Hair Growth

Although we understand how and why young women in the modern age are so reluctant to voluntarily nurture their facial hair, it’s true that facial hair growth in women is much less prolific than in men. Now, let’s try to understand the scientific reasons behind this difference.

Scientists working in the domain of neurosciences state that men have thick facial hair in the form of mustaches and beards for a very specific reason. The inception of facial hair for both men and women starts in the hypothalamus—a section located at the base of the brain. The hypothalamus sends signals to a gland called the pituitary gland. The pituitary gland then sends signals that trigger the ovaries in girls and the testes in boys. You might have learnt in school that the ovaries help to produce a hormone called estrogen in girls. On the other hand, the testes help to produce a hormone called testosterone in boys. The rigorous activity of these two hormones help to push our bodies into puberty.

Boys become more “masculine” with an increase in testosterone levels, while the elevated estrogen levels make girls more “feminine”. Many studies have shown that the large amounts of testosterone in the body stimulate the fast and rapid growth of facial hair. As girls have more estrogen than testosterone, their facial hair growth is not as prolific. Thus, girls who have problems with rapid facial hair growth have often been found to have higher levels of testosterone than normal. So, while higher levels of estrogen may help girls keep their facial hair growth in check, having a permanently and completely hairless face is preposterous for anyone!

Evolutionary Tales

The unusual hairlessness of humans compared to our closest living relatives, the chimp continues to baffle researchers studying human history. Why did we lose all this hair? So far they’ve come up with a host of theories that try to answer the question.

The discussion, as any good discussion on evolution, starts with Darwin. In 1871, Darwin wrote a book called ‘The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex’. In the book Darwin looks at humans through the evolutionary lens, talking about one aspect of evolution called sexual selection.

Darwin defined sexual selection as “the advantage which certain individuals have over others of the same sex and species, solely in respect of reproduction”. What this means is that certain traits are sexier than others. This would be a lioness preferring to mate with a lion with a bigger mane. Or a male deer with bigger antlers getting the female deer. All these flashy accessories aren’t crucial to the animal’s survival. Rather, these accessories indicate the quality of the DNA. A bigger mane on a lion tells the lioness, “This lion is strong and his DNA will make my future kids strong too”. If you’ve seen a National Geographic animal documentary, you know what I’m talking about.

Darwin proposed that prehistoric men preferred women with lesser hair. He came to this conclusion based on the fact that women were naturally less hairy than men. The men also got less hairy because of inevitable genetic mixing. Over generations, this was proposed to have led to humans having the weird nakedness of today. These proposals had ramifications on how Victorian men and women thought about their body hair.

In addition to being sexist, the theory fails to identify what triggered hair loss in the first place. What cause women to start becoming less hairy? Why would less hair be more attractive? There are several theories vying for the trophy of being ‘the answer’. But none of them tells the full story.

The most popular theory today is the ‘Savannah Man in Africa theory’. Proposed by Raymond Dart, a South African anthropologist and anatomist, the theory argues that less hair was an advantage for hominins who had begun hunting in the savannahs of Africa.

Fur is an insulator. It traps heat in keeping animals warm when outside temperatures are too hot. In the direct heat of the savannahs, somewhere no chimp or ape lives, early hominins needed a way to cool off. The best way to do this would be to lose hair and develop sweat glands. Humans sweat much more than any other animal. Only the horse has a comparable sweating capacity.

Looking at genes supports the theory. A 2001 study found that the I hair keratin pseudogene ϕ hHaA has functional versions (orthologs) in chimps, which make them hairy. The study gives evidence that this gene might have become inactivated when early humans diverged from chimpanzees.

Another study conducted in 2004 found a variant of the MC1R gene. The variant of the gene, which is thought to be important for the darker colour of humans, was already present 1.2 million years ago. Skin darkening wouldn’t have occurred if humans weren’t already losing hair.

Other theories are less popular and have several loopholes. One theory suggests that humans became less hairy because it made them more sensitive to ectoparasites like bedbugs. Another theory suggested by James Giles proposes that less hair made skin to skin contact between mother and child increase. This increased the mother more nurturing towards her offspring, leading to selection of less hair. Males got less hairier along the way because of DNA mixing. None of these have any genetic evidence backing them up.

In The Pursuit Of Smooth Skin

Though, humans are naturally hairless, history shows us that we artificially began to get rid of hair. The Egyptian, the ancient pioneers of beauty regimens, would shave the hair off their head and bodies.The Romans, too associated lack of body hair with a higher social and class status. They used razors made from flint, tweezers made from seashells, pumice stones, waxes such as beeswax and other sugar waxes (Cleopatra was thought to have used some sugar based wax to remove her hair).

By the time the Middle ages came around, hair removal and make trends had gotten even more bizarre. Elizabeth I was what we would call a fashion icon of her time. She is thought to have popularized shaving off the eyebrows and hair from the forehead to have a longer and larger looking brow.

As mentioned earlier, Darwin’s theory of evolution and sexual selection really caught the Victorian public’s imagination. It was after Darwin’s work that hair removal moved away from hygiene matters and class dynamics to an idea that defined the difference between masculinity and femininity. Gender and sexuality professor Rebecca Herzig points to Darwin’s 1871 book ‘The Descent of Man’, which incited women to turn against their facial hair, as I mentioned earlier.

Darwin’s book not only introduced the idea of sexual selection, it also justified much of human sentiment on hair through an evolutionary lens. He argues that a hairy body becomes a breeding ground for parasites and lice. Thus, a face without hair implies more hygiene and attractiveness, making a clean-faced woman a preferred choice for mating.

Darwin’s work in Descent of Man had its roots in traditions of comparative racial anatomy, and his evolutionary theory attested hair’s associations with ‘primitive’ ancestry and hairiness in females being implicitly linked to ‘less developed’ forms of living beings. Herzig opines that after the publication of Darwin’s work, hairiness became an issue of fitness.

Anthropologists, following the work of Darwin, professed that hairiness was one of the external factors for clear the distinction between masculinity and femininity. Less hair in women indicated “higher anthropological development”, so hairiness in women became an anomaly. Women themselves associate removing facial and body hair with feeling feminine (Source)

In one research study conducted in the 1890s studying insanity in women claimed to find that 271 cases of insanity in women were linked with excessive facial hair. Moreover, those supposedly ‘insane’ women had thicker and stiffer hair. Havelock Ellis, a renowned scholar of human sexuality, claimed that heavy hair growth in women is often linked to criminal violence, strong sexual instincts and unforgiving animal vigor.

But many of these attitudes towards are a product of a culture’s prevailing zeitgeist. Afsaneh Najmabadi, a gender and sexuality professor from Harvard, echoed Herzig’s point. During her research, Najmabadi has found that the literature of the 18th century depicted Iranian women with heavy brows and faint mustaches on many occasions. In fact, these features were considered so attractive that they were sometimes painted on by renowned artists or augmented with mascara. She discovered that, until the early 19th century, the gender distinction in portraits of lovers was very vague and it sometimes became difficult to discern males and females!

By the early 1900s, facial hair was an important source of discomfort for women in the US. Their desire for smooth, sanitized, white skin was insatiable. They wanted to be feminine and having a hairless face was a quintessential example of feminism. In her book Plucked, Herzig explained how in a very short time period, facial hair became despicable to middle-class American women—its removal seemed a necessity to separate themselves from the cruder atavistic human community.

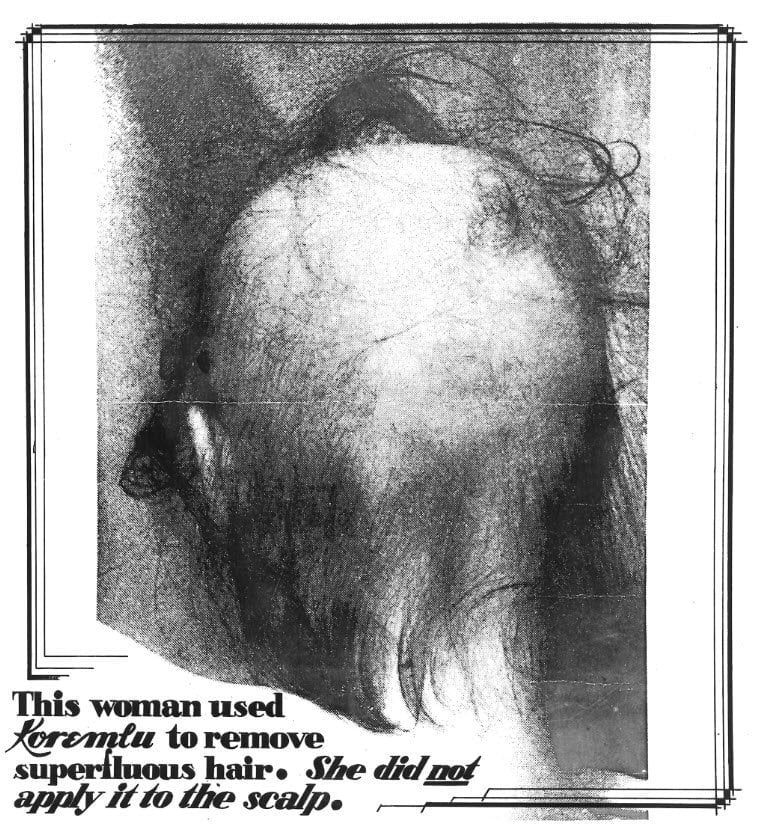

Women started using pumice stones or sandpaper in the 1930s and 1940s to remove their facial and body hair, but this often caused irritation and scabbing. Koremlu, a cream made from thallium acetate, was making the rounds among the cosmetic kits of young women in the 1930s. Although Koremlu advertised itself as a safe and permanent hair-removing cream, it was made from thallium acetate, which is actually rat poison! Thousands of unsuspecting women faced severe health issues and the blighted cream cost the lives of several women. Koremlu was successful in eliminating hair, but it resulted in serious health implications that included blindness, limb damage, and at the very worst—death.

Cost Of Hair Removal

The removal of facial and body hair is ubiquitous in the modern female population. According to one study, more than 99% of American women voluntarily rid themselves of their facial or body hair. Mind you, hair removal is pretty darn expensive!

Other studies have pointed out that American woman typically spend more than $10,000 over the course of their lives to shave off their hair. This cost can balloon up to a whopping $23,000 for women from wealthier backgrounds who use waxing for hair removal, rather than shaving. These habits to get rid of hair, especially facial hair, is not restricted to the US; women across different races, ethnicities, and nationalities would agree that it’s almost “mandatory” for them to have a smooth, clear and hairless face.

But more women are reclaiming their hair. Recent trends such as the glitter armpits or dying your armpit hair a vibrant colour are ways that many women are rebelling against the standards 100s of years of history has placed on them. Body positive activists are urging women to love themselves in any shape or form, whether that’s with hair or not. Though, the majority of women still shave, wax, thread, pluck and scrub their hair off, there is a change about demanding more acceptance.