Table of Contents (click to expand)

The process of colorizing black and white films has evolved over time, from hand-painting each frame to using computers to digitally color individual objects. The most recent method of colorization uses software to color each pixel, which is then blended together to create a continuous image.

With the advent of filmmaking, the visual dissemination of ideas finally took place, freeing us from the arduous task of evoking the images that the task of reading imposed on us. The plot could now unfold before our very eyes. Although films achieved what books took days for in a few hours, the media still imitated their textual cousin – the films were black and white.

However, the generic term is misleading: the films were not black and white, but in fact, grayscale, all objects in the films reflected a certain shade of gray.

Of course, this was due to technological constraints. As technology advanced, the filmmakers could present their ideas more “naturally” or rather more humanly.

As the color palette grew, the panoramas became more radiant. However, revered masterpieces such as Casablanca could not simply be recreated in color.

To witness Humphrey Bogart’s turquoise eyes and the glowing orange butt of his cigarette, one would have to reassemble the entire cast and make the film all over again, which would lead to a public outcry – partially because Bogart has been dead for the past 60 years. More importantly, however, remakes have always been frowned upon. While making a remake, one isn’t just tinkering with a highly cherished work of art, but people’s expectations and beliefs attached to it.

Remakes aside, the films can be colorized.

Recommended Video for you:

Painting Movies, Literally!

Elisabeth Thuillier was a French colorist who excelled in painting facets of magic lanterns and other photographic works. Elisabeth and her 200 collaborators – all women – were often engaged by French filmmaker George Melies to color his films. Classics include A Trip to the Moon and The Kingdom of Feiries.

They began coloring film around 1897 in a coloring lab in Paris. The colorization method was initially hand done by individuals. Yes, the employees literally painted every object in every frame one color at a time. They formed an assembly line in which each colorist was assigned a single tone, filling particular parts of each frame before passing the film to the next employee. Some areas were so minute that the employees resorted to brushes with a single hair!

Elisabeth used aniline dyes that produced transparent and luminous tones. She dissolved the dyes first in water and then in alcohol before smearing them on the foils. As on the palm of a standard palette, different colors were mixed to create various colors.

Elisabeth used four primary colors: orange, blue-green, magenta, and bright yellow. These primary colors yielded more than 20 unique colors. The colors to be used depended on the shade of gray on the underlying foil.

Manual Colorization Was Too Laborious.

The efficacy of the process was questionable, but this was, of course, a remarkably time-consuming process. Colorization by hand was done as late as the 1920s, but it was seldom used to create entire films, such as The Last Days of Pompeii.

These inefficient methods soon saw themselves fall out of fashion as computerized colorization technologies were introduced.

Digital Colorization

Not only did coloring with the computer make the image quality crisper and more exquisite, but it also required less time. The advent of the computer made coloring much more effective.

It was similar to coloring by hand, but now the film was colored on the computer. Studios were able to revive black-and-white images by digitally coloring individual objects in each frame of the entire film until they were fully colored.

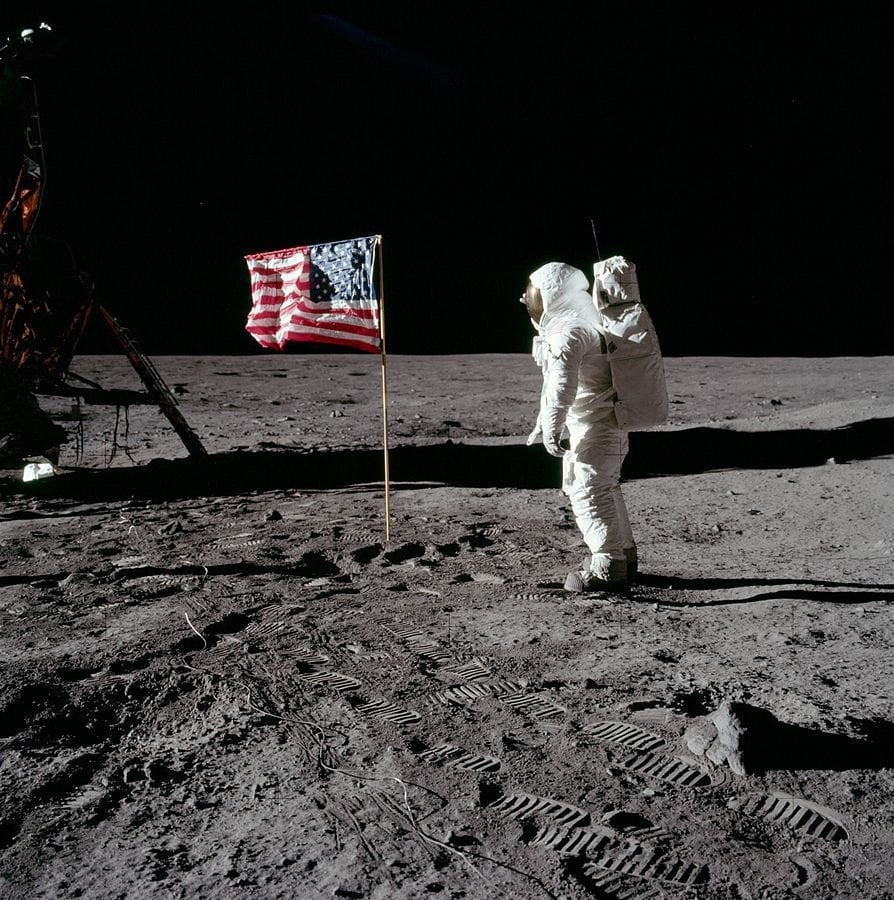

Inspiration From NASA’s Mission

This technology was invented by former NASA engineer Wilson Markle after entrusted with colored monochrome shots of the Apollo missions to the Moon. The basic logic was reminiscent of hand coloring – in every scene, Markle ascribed predetermined colors to shades of grey. He foresaw the technology’s commercial prospect and subsequently founded Colorization Inc., which caused the term “colorization” to become ubiquitous.

Still, the techniques generated tawdry images with minor contrast, and they were often mildly pale with an appearance of colors being washed out. A few years later, advancements in technology facilitated the advent of digital signal processing and graphic software to better manipulate complex imagery.

Working On Pixels

The technique required a digitized copy of the best monochrome print of the film. Here, too, the gray area is at the center of the transmutation. This time, the shades are assigned by the complex software. The objects are divided into infinitely small, indivisible areas called pixels.

Afterward, the technician colors each pixel. Our eye then perceives the pixels, or rather blurs them into a continuous image.

![]()

Markle’s method used up to 4000 shades of color to fill individual pixels. Other than simply coloring, the software is also capable of sensing tiny variations in the level of light in the frames to detect movement and correct them if necessary. To account for movement, the moved pixels were simply recolored.

A majority of colors are “obvious” colors, such as blue sky, white clouds and green grass. Other colors were assigned based on acquired information of the props used in the film or the film’s available pictures. In case the technician is unsure about an object’s color, he decides on a color he feels is consistent or is characteristic of the grey scale. Or, he may presumptuously select a color he feels the director might have chosen!

The software then colors the object in every frame until it exits the frame. The entire procedure is then repeated for each object.

Without algorithms for recognizing consistent boundaries, such as a boundary for distinguishing between an actor’s hair and face, coloring each pixel can be an extremely tedious process.

The Criticism Of Colorization

Digital coloring would cost an exorbitant $3000 per minute for a film! The average cost of an entire feature film would be an absurd $300,000!

Why would media companies intentionally burn such a deep hole in their pockets? Is it because they are exuberant philanthropic aesthetes?

Not really.

People even from the remotest corners of the world were lured by the prospect of seeing their favorite movies in color. Average earnings for these renovated films were about $500,000, almost double the spending!

A filmmaker could make a fortune by simply removing a film from the classics list, coloring it and selling it to the masses.

Roger Ebert On Film Coloring

This kind of manipulation is vehemently loathed by film critics, filmmakers, and artists. For Roger Ebert, this tampering was tantamount to vandalism. He writes: “They arrest people who spray subway cars, they lock up people who attack paintings and sculptures in museums, and adding color to black and white films, even if it’s only to the tape shown on TV or sold in stores, is vandalism nonetheless.”

He added, “What was so wrong about black-and-white movies in the first place? By filming in black and white, movies can sometimes be more dreamlike and elegant and stylized and mysterious. They can add a whole additional dimension to reality, while color sometimes just supplies additional unnecessary information.”

Critics loathed the media giant Ted Turner, who embarked on a classic coloring tour, and resentment intensified when he decided to paint Citizen Kane.

Technically, black-and-white films illustrate the truest representation of reality. Seduced by a love of black-and-white, filmmakers, despite the availability of color technology, persisted in shooting films in shades of gray.

Think of Woody Allen’s Manhattan, which used shades of gray to illustrate his immaculate view of New York, or Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, shot in black-and-white to intensify visual imagery, or The Artist , whose visual monotony evokes nostalgia.