Photochromic glasses work by containing specialized optical lenses called photochromic lenses. These lenses automatically darken in the presence of certain types of light, usually ultraviolet light, and become clear again in the absence of that light. Photochromic glasses may be made of different materials, including glass, plastic, or polycarbonate.

I remember back when I was in school, there was a classmate of mine who used to wear glasses. However, these were not your run of the mill corrective glasses; they were something much more unusual. They automatically became dark when he played outside, but cleared up when we were indoors.

I asked the guy about his ‘magic glasses’, and he rather proudly announced that they were photochromatic glasses.

In this article, we’re going to talk about those type of glasses and the science behind them.

Recommended Video for you:

How Do Photochromic/photochromatic Glasses Work?

Short answer: Modern photochromic glasses, usually made of plastic, contain carbon-based molecules that change their molecular structure when UV light strikes them (and thus they absorb more light) and become dark. Similarly, in the absence of UV light, the molecules reverse to their original shape, making the glass clear once again.

What Are Photochromic Glasses?

Photochromic glasses consist of specialized optical lenses called photochromic lenses that automatically darken in the presence of certain types of light (usually ultraviolet light) of adequate intensity, and become ‘clear’ again in the absence of that particular light.

Also referred to as photochromic lenses, they are primarily used in sunglasses and windows that darken within a minute or two when the sun shines too brightly, and they become clear in a few minutes in low ambient light conditions. Photochromic glasses may be made of different materials, including glass, plastic or polycarbonate.

Photochromic lenses were invented by William H. Armistead and Stanley Donald Stookey of Corning Glass Works in the early 1960s. The design of those preliminary glasses, however, was quite different from the ones we commonly see these days.

How Do (Regular) Sunglasses Work?

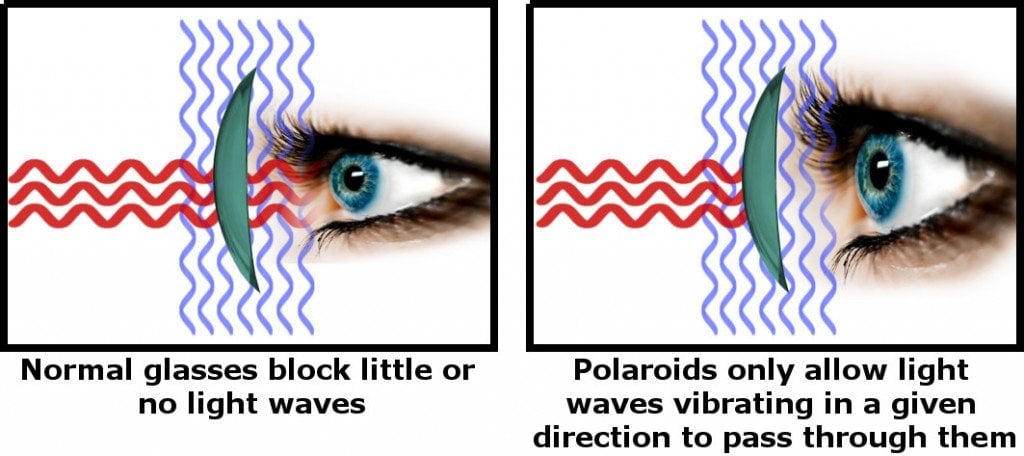

Regular sunglasses (those that aren’t photochromic) have a basic working principle: they block out light of a specific wavelength. This is done in one of two ways: the first type of sunglasses uses colored filters. What these filters do is only let a specific color of incoming light pass through them.

The second type of glasses relies on an optical phenomenon called polarization. Such glasses only let those light waves pass through them that vibrate in a given direction.

How Do Photochromic Glasses Work?

Early photochromic glasses were usually made of glass and contained small crystals of silver halides (e.g., silver chloride) that darkened when exposed to light, just like old photographic films.

However, unlike those films, the darkening of photochromic lenses was reversible, i.e., the lenses became clear again once the ambient light was lowered. The crystals used in the glass of such lenses were minuscule, both in number and size. Fewer than 0.1% of silver halide crystals, which were 100 times thinner than a human hair, were used in early photochromic glasses.

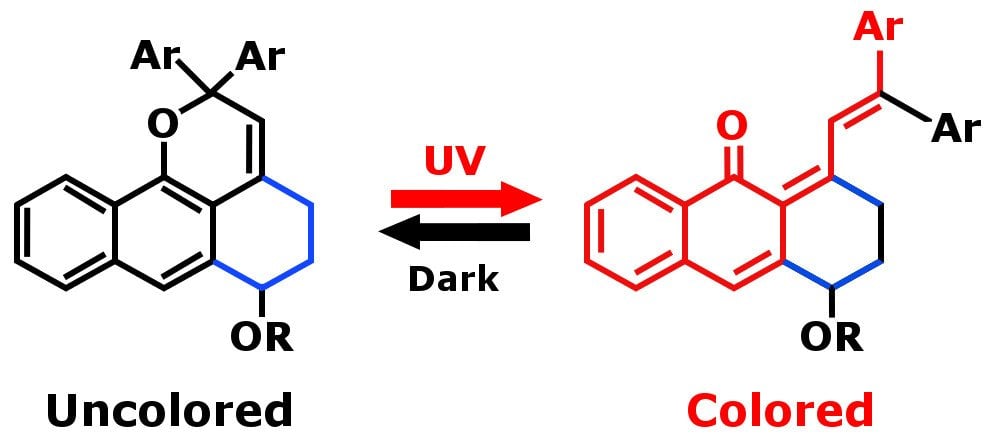

Modern photochromic glasses, however, are usually made of plastic, rather than glass, and contain carbon-based (organic) molecules instead of silver compounds. Such compounds are better, more efficient alternatives for achieving the quick-darkening and quick-clearing effect, as their molecular structure varies in accordance with the presence/absence of a certain type of light (usually ultraviolet light, as it’s a component of sunlight).

The most commonly used photochromic molecules are naphthopyrans and oxanes, due to their ability to change their molecular structure reversibly upon exposure to UV light. Below is a generic example of such a reaction:

Drawbacks Of Photochromic Glasses

One of the most commonly reported drawbacks of photochromic glasses is that they take somewhat longer to clear than to darken. For example, if a person walks indoors after being in the sun for a while, the glasses will allow only about 60% of light to pass through them for the first 5 minutes. Additionally, they could take as long as an hour to clear completely and become fully transparent again!

Another major drawback is that since the photochromic compounds rely on the presence of heat and light to undergo changes, such glasses are found to be more effective in winter and less so during summer (when you need them the most!).

People also report that photochromic glasses are less effective inside cars and other automobiles. This is because the glass windows of these vehicles block UV rays to a great extent themselves, so the photochromic molecules present in your glasses don’t receive enough UV rays to undergo changes and be effective.

Notwithstanding these few drawbacks, there’s no doubt that photochromic lenses represent a brilliant piece of optical engineering and are very convenient for people who don’t want to switch glasses every time they head outside!

References (click to expand)

- Photochromic lens - Wikipedia. Wikipedia

- How do Transitions® photochromic lenses work?. explainthatstuff.com

- Sousa, C. M., Berthet, J., Delbaere, S., & Coelho, P. J. (2012, April 9). Photochromic Fused-Naphthopyrans without Residual Color. The Journal of Organic Chemistry. American Chemical Society (ACS).

- Eppig, T., Speck, A., Gillner, M., Nagengast, D., & Langenbucher, A. (2012, January 4). Photochromic dynamics of ophthalmic lenses. Applied Optics. The Optical Society.