Table of Contents (click to expand)

Lighters are containers that use a fuel to produce a flame. The first lighters were fueled by hydrogen gas, but modern lighters use butane. When the lighter is depressed, the butane is released and vaporized. The vaporized butane is then ignited by a spark.

Lighters are to smokers what sunlight is to trees, but lighters aren’t merely used to light cigarettes. They’re also quite common at any party that involves a cake dug with candles. However, have you ever wondered how lighters produce a flame so perfectly ovate, as if it materializes from a candle, out of thin air?

Recommended Video for you:

The First Lighter

The first aspect is obvious: the fire produced is the result of the combustion of a fuel. The lighter is nothing but a vessel for this fuel. One of the very first lighters, whose invention is credited to a quirky German chemist named Johann Dobereneir, stored hydrogen gas. The gas – a gaseous product of a chemical reaction – would waft over a heated platinum catalyst, which would set it ablaze.

The flame was gentle, but exuded an unpleasant odor. Still, Johann’s invention made igniting fires to cook food or burn pipes extremely quick and convenient. His invention’s commercialization saw him earn a fortune around the late 19th century. He apparently sold over one million of these lighters!

The Modern Lighter

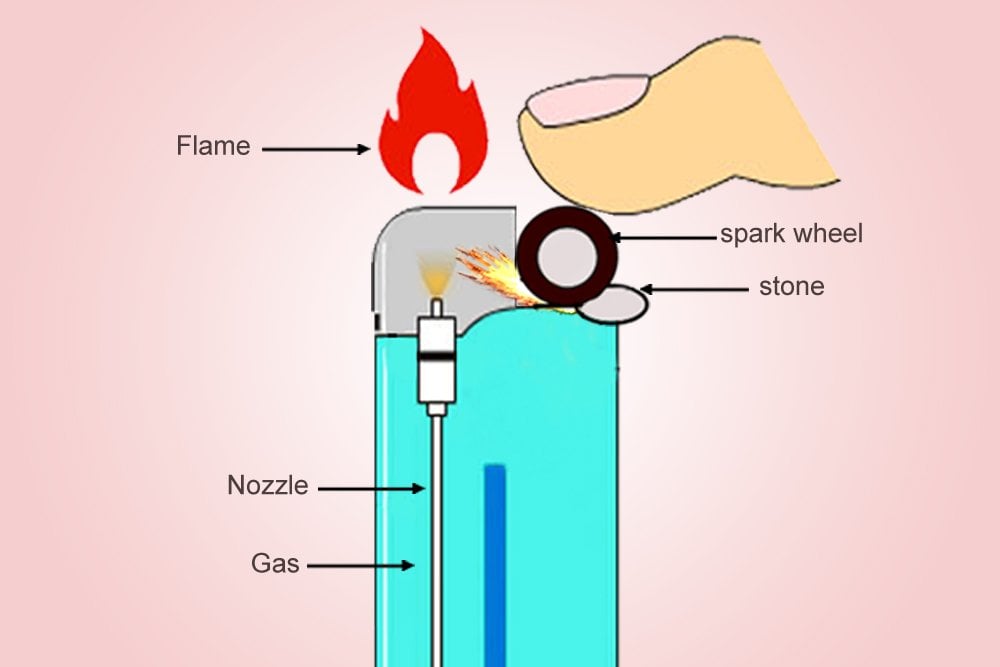

The modern lighter couldn’t have been born if Austrian chemist Carl Auer Von Welsbach hadn’t invented ferrocerium, an alloy of iron and cerium, a rare metal, that emanates sparks when oxidized rapidly. One way to achieve this is to strike it against an object. The sparks, which reach temperatures of up to 3,000 ᵒC, can be used to ignite lighter fuels and cutting torches.

The modern lighter doesn’t store hydrogen, but butane. It initially stored naphtha, until we realized that butane produces a more controlled flame and exudes the least amount of unpleasant odor. Butane in a lighter is pressurized and stored, which causes it to exist as a liquid. When depressurized, the liquid will immediately vaporize to form gaseous butane. The gaseous butane, being flammable, will catch fire even when incited by the slightest of sparks.

The metallic wheel on the lighter, when pushed down by one’s thumb, will rub against the ferrocerium to produce a scorching spark. Simultaneously, a valve opens, from which the butane is released, which is vaporized (depressurized) as soon as it exits the container. The spark is produced just above the valve, which then simply ignites the plume of gas. The result is an ovate, tranquil flame.

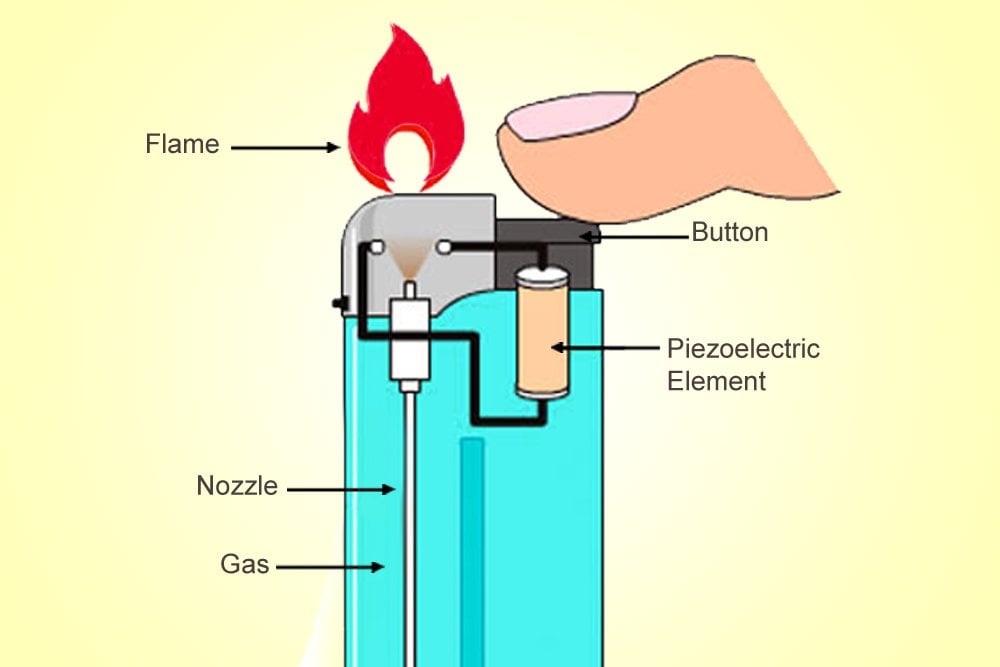

The ‘Clippers’ or ‘Zippos’ that implement this mechanism are a delight for an aesthete, but are also more expensive. Cheaper lighters use a piezoelectric material that converts mechanical energy to electric energy. Unlike ferrocerium, a piezoelectric material isn’t pyrotechnic, but its electric resistance changes when it is deformed by mechanical forces.

When you “click” such a lighter, the piezoelectric material deforms and bears a current. Above the valve through which the butane exits, two separated wires produce between them what is called a voltaic arc, an electric discharge or plasma, like the thorns of current surrounding Thor. This discharge, like a spark, will ignite the depressurized gas and produce a candle-like flame.

The invention of an igniter is regarded to be as crucial to the progress of our civilization as the invention of the wheel, perhaps, even more important. Without fire, cooking food would have been impossible, without which we would have been unable to kill its harmful germs and leverage its nutrients. It’s no wonder that Stephen Fry believes the lighter to be our greatest gadget. It allowed us to summon a member of the pantheon, at our whim, or as Fry said, with merely “the flick of our fingers.”