Table of Contents (click to expand)

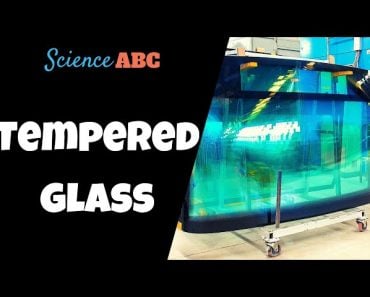

Heads-up displays or HUDs use collimation and beam splitting to project a transparent image on a transparent surface.

Man’s deepest fantasies, ranging from epic emotions to planetary conquests, are exhausted through movies. At the same time, what appears silly to some audiences could strike a chord with a mad scientist in the crowd. And before we know it, that marvel from a movie is suddenly part of our lives.

With that in mind, how far are we from J.A.R.V.I.S in reality? Yes, the same AI-powered assistant of the legendary Tony Stark, aka Iron Man.

Recommended Video for you:

Augmented Reality

As to how close we are to making J.A.R.V.I.S a reality, I can’t say, but what suffices for now is the presence of augmented reality. Not only does this tech exist, but it’s growing in leaps and bounds. The days of clumsy wearable boxes that showed us things that didn’t actually exist in that space at that time are now behind us.

Today, AR is integrating with our daily utilities seamlessly, rather than being a standalone unit to be used separately. Enter the Heads-Up Display (HUD).

What Are HUDs?

The need for war pilots to remain engaged in combat maneuvers without looking away to consult their dials led to the genesis of HUDs. Today, this technology serves more domestic applications, such as wearables and automotive gadgets.

A HUD unit essentially projects useful information on the glass through which a user is already looking. The information projected is transparent, so that it doesn’t block out the situation being viewed. At the same time, it is clearly visible and within the user’s field of view, so that no information is lost.

How Is It Done?

Projecting images on screens is no big deal; humans have been doing this for many years now. The biggest feature of interest however, is being able to display transparent information on a transparent screen, without losing information or visibility. How is this achieved?

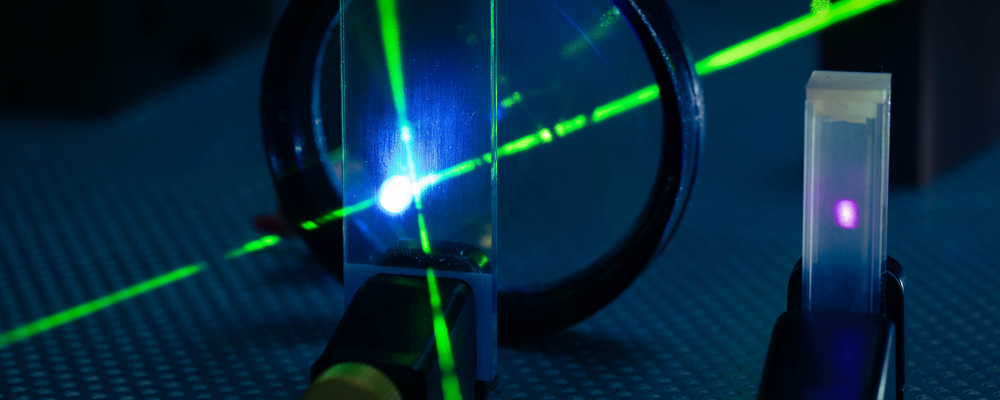

A heads-up display usually consists of a source of light, such as a cathode ray tube, phosphor crystals or LED. These are placed at the focal point of a reflector or lens, which enables them to generate images that are perceived to be at infinity. In optics, this process is known as collimation.

Going further, the light rays are passed through a combiner, which splits the beam of light. One segment of this beam is directed at the pilot’s eyes, while the other, through the glass, at perceived infinity. These two images overlap, which gives the impression of images being projected on glass.

The most important part of a HUD is the computer, which grants purpose to the aforesaid optical manipulation. The computer collects information from the vehicle and converts it into light signals that get projected in front of the pilot. Today, LED and LCD are preferred over CRT due to their more robust and compact construction.

HUD Design Considerations

By nature of their design, HUDs risk losing their functionality to more conventional dials and screens, if their visibility is not optimal. Thus, there are several design considerations to be made when they are designed for a particular application.

1. Visibility

Color, contrasts and resolution are the biggest considerations in HUD design. Since the landscape rapidly changes for vehicles in most scenarios, the display must be clearly visible in all circumstances. At the same time, the pilot’s field of vision, and the distance at which they sit from the HUD unit, also known as the eye box, should be taken into account.

Most cockpits will have some form of manual and automatic adjustability built into them, to ensure that the HUD remains useful for most pilots. It is also important to design HUDs to work around polarized eye wear. Most non-critical HUD units are not compatible with polarized eye wear.

2. Parallax

The horizontal distance between human eyes is the reason for an object ‘jumping’ when viewed through the individual eye. This can present great concern where HUDs present critical data, such as orientation and the scale of objects. Thus, using a collimator is extremely important, as it projects the image at perceived infinity, and significantly eliminates parallax.

3. Scaling

It is commonly experienced that objects distant to us appear much smaller than they actually are. Since HUDs superimpose over objects that are visible through the screen, they must compensate for the change in scale as the objects come closer. This change of scale should also be communicated to the pilot by changes in the defining parameters.

4. Boresight

Boresighting refers to the process of aligning an object with respect to the three axes in real time. This is especially true in case of aircraft, where HUDs are used for determining their orientation with respect to the artificial horizon.

Applications

HUDs are already found in high-end automobiles, where they display vital information such as navigation, speed, RPMs, and in some cases, even the braking distance between two vehicles.

They are slowly making their way into more budget-friendly cars as a way to improve their appeal to the mass market. They are also an emerging trend in wearable technology where they integrate with eyewear.

However, their most prolific use remains in the realm of aviation and warfare. HUDs finding use in these areas usually have multicolor displays, which are capable of displaying symbolic information, such as altitude and orientation, alongside more graphical information such as terrains.

Advanced heads-up displays are also capable of displaying thermal signatures and night vision. HUDs fitted in the helmets of fighter pilots have an eyeball tracking system that enables them to cue and fix targets based on where the pilot is looking. This greatly reduces their reaction time, which is of utmost importance in the midst of war.

A Note On Ingenious HUDs

What if you have an old car and a tight budget, but a knack for being tech-savvy? Software developers have made a dinky little workaround that lets you have your own HUD for no additional cost! All you need to do is download an application on your smartphone.

The application derives data, such as speed and direction, from dedicated apps and GPS connectivity in the phone and displays them on the phone screen. However, the catch is that the data is displayed in an inverted manner. The phone must be placed on the dashboard where the windscreen meets the car body, and the inverted image is then reflected onto the glass.

Since no glass can reflect or transmit light completely, it is possible to get a reliable visual dashboard without incurring additional costs. Some companies even sell dedicated screen attachments on which the visual can be reflected much more clearly than it would be on the windscreen!