Table of Contents (click to expand)

Pistons are cylindrical machine components that perform reciprocating motion in a pressure-tight tube, to either impart or derive motion.

We’ve all come across syringes at some point in life, the instruments used by doctors to inject medicine to ward off the invisible threats continually attempting to prey on us. Physically speaking, a syringe has a hollow barrel with a needle at one end and a manually operable plunger at the other. The barrel and the plunger are the simplest forms of a ‘cylinder-piston’ arrangement—an essential part of many machines.

Recommended Video for you:

What Is A Piston?

A piston is defined as a cylindrical component that performs reciprocating or back-and-forth motion in a pressure-tight tube. The purpose of this arrangement is to pressurize fluids (both liquids and gases) contained within the cylinder to either impart or derive motion.

Construction Of A Piston

Even though pistons have a myriad of shapes and applications, the basic structure of all pistons remains the same.

1. Piston Body

The piston body consists of two integral components: a crown and a skirt. The piston crown is the uppermost surface of the piston, which comes in contact with the fluid. Pressurization is achieved by the movement of the piston head towards the topmost position.

The piston crown sits on an integrated hollow cylindrical shape, which fits closely into the outer cylinder where the reciprocating motion is performed. The piston skirt, as it is known, has grooves running parallel to its cross-section in order to accommodate piston rings.

While the piston skirts are not prominent in manually operated devices, they constitute a significant part of the piston structure in mechanical devices. Apart from housing the piston rings, they also accommodate the hub and bushings, which help hold connecting rods in place.

2. Piston Rings

To compress or pressurize fluids, it’s essential to maintain a pressure-tight seal between the inner cylinder wall and the piston. This is achieved using piston rings made of special materials; these rings not only expand to fill clearances between the cylinder wall and the piston, but also retain their configuration under duress. Piston rings also keep the cylinder lining clean at all times.

3. Connecting Rods

As we already know, pistons can either impart or derive motion through the pressurization of fluids. The connecting rod transmits this motion from an energy source at one end and an energy recipient at the other end. In a syringe or any other manually operated machine, connecting rods are usually fixed to the base of the piston head, and may also be called pushrods.

In the case of complex machines, such as engines and pumps that rely on a thermal or electrical power supply, connecting rods pivot around a wrist pin on one end and bearings on the other.

4. Wrist Pin

Connecting rods pivot around a pin that helps push the piston crown up and down. This pin is known as a wrist pin or gudgeon pin, and fits into the bushing of the piston skirt. Wrist pins are only present in pistons that have moving connecting rods.

How Pistons Work

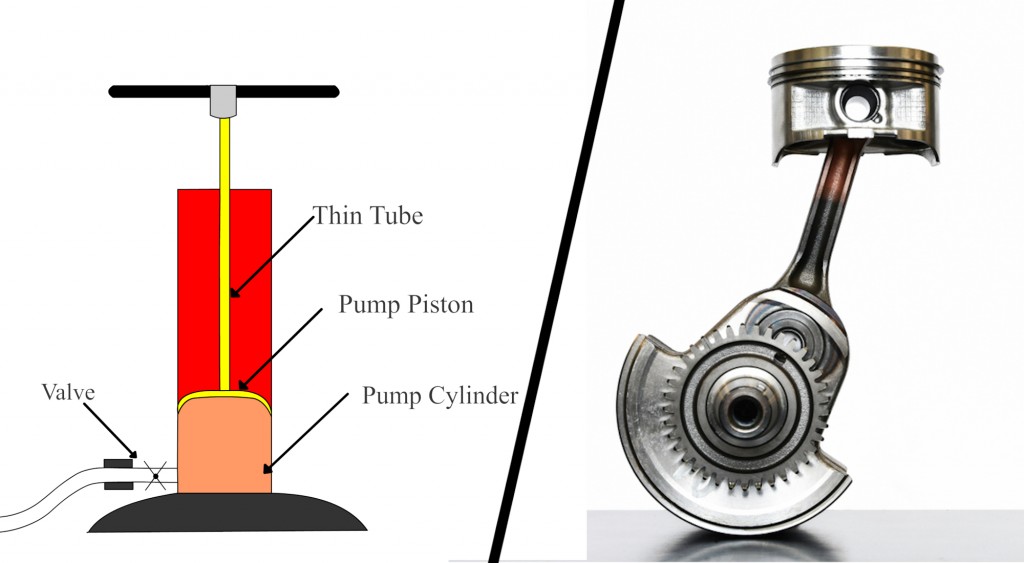

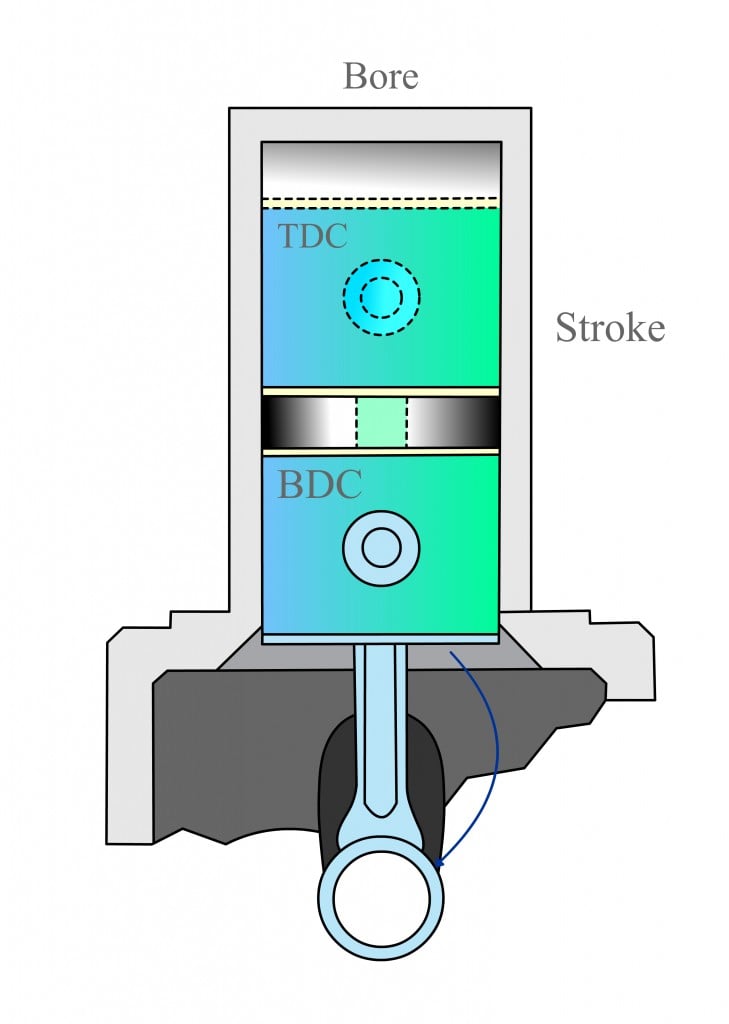

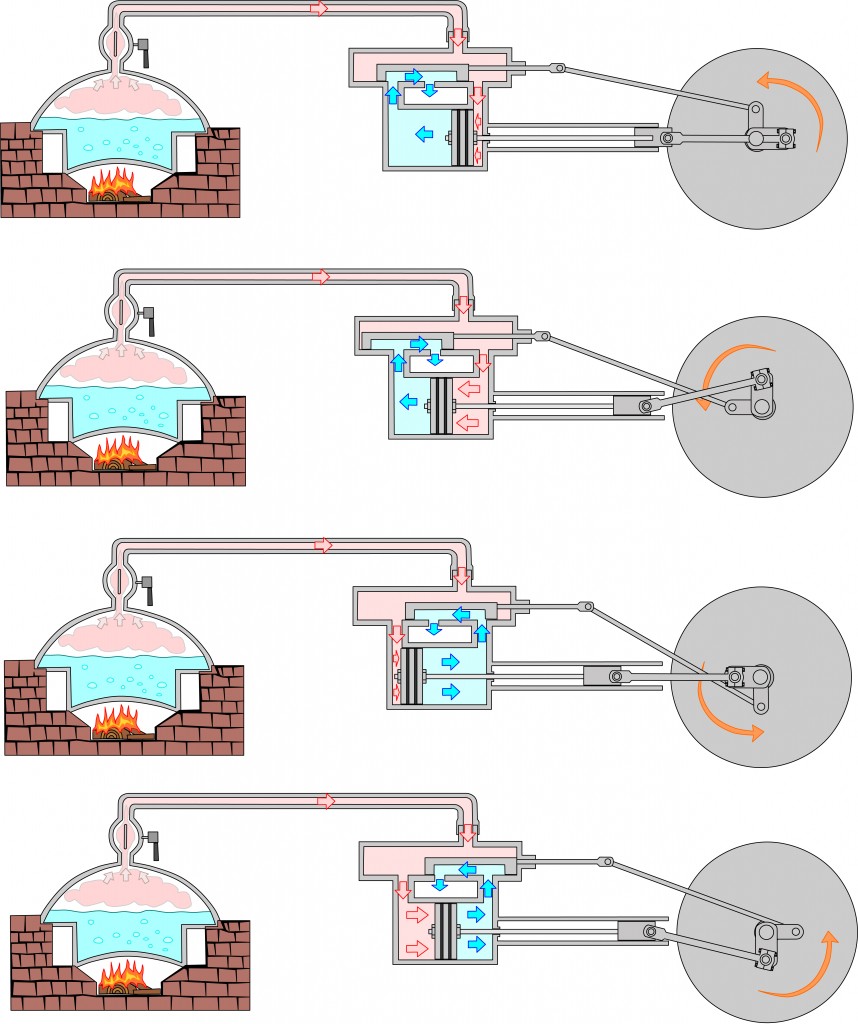

The cylinder in which a piston reciprocates has valves that enable the ingress and egress of fluids. As a piston moves downwards, intake valves open to admit the fluid into the cylinder. The piston can then move to an extreme position, away from the upper surface of the cylinder. This is known as the bottom dead center (BDC).

At this stage, the intake valve closes, and the piston begins to travel upwards, reaching an uppermost extreme, known as the top dead center (TDC). Pressurizing and the compression of fluids takes place as the piston approaches the top dead center. The outlet valve opens at this point to push the compressed fluids out of the cylinder.

Every movement between the top dead center and bottom dead center is known as a stroke. In pistons that are arranged laterally, rather than vertically, the extreme positions are known as the inner dead center (IDC) and outer dead center (ODC).

Single And Double-acting Pistons

A conventional piston pressurizes fluids only in its forward stroke. Such a piston is also known as a single-acting piston. However, certain pistons pressurize fluids in both the forward and return strokes. This is made possible by using a fixed connecting rod and pressure-tight surfaces at both faces of the piston crown. Such pistons are known as double-acting pistons.

Application Of Pistons

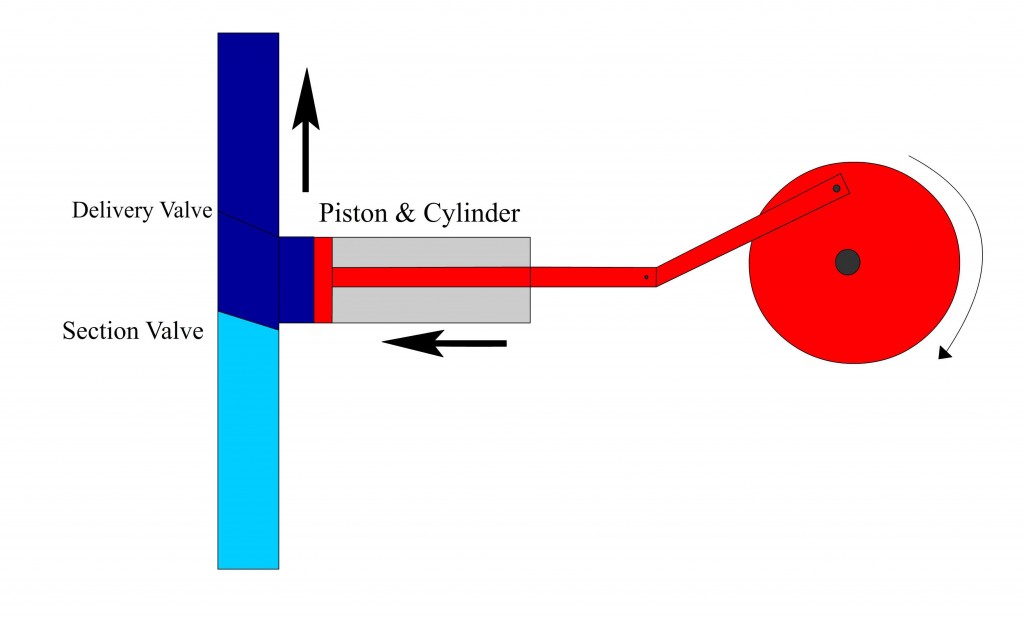

1. Reciprocating Compressors

These devices induct gases at low pressure and eject them at a higher pressure, utilizing mechanical power from a crankshaft connected to an external power supply. Reciprocating compressors are two-stroke: the return stroke draws in air at low pressure, while the forward stroke compresses it and pushes it out of the cylinder at high pressure. Compressors therefore impart motion to fluids.

2. Reciprocating Pumps

While it is common to use pumps and compressors interchangeably, pumps serve a slightly different function, as they are used to pressurize liquids. Liquids cannot be compressed like gases, but they can be released at higher pressure, which comes at the expense of velocity. Pumps, like compressors, impart motion, but due to the availability of superior options, reciprocating pumps are not commonly used for liquids.

3. Engines

An engine compresses fluids (air-fuel mixture), which ignites to push the piston downwards. The piston, in turn, moves the crankshaft. In two-stroke engines, pistons also serve as inlet and outlet valves. Thus, engines, unlike pumps and compressors, derive motion from the combustion of compressed fluids.

4. Manually Operated Devices

Ink cartridges, syringes and bicycle pumps utilize pistons with fixed pushrods. They derive power from physical effort to displace fluids at high pressure.

5. Steam Engines

Steam engines, though now obsolete, utilized double-acting pistons. These days, double-acting pistons are used on special-purpose hydraulic and pneumatic systems.