Table of Contents (click to expand)

Scientists are trying to bring back extinct animals through a process called de-extinction. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) guidelines define de-extinction as the generation of proxies of extinct species that are functionally equivalent to the original extinct species, but are not ‘faithful replicas’.

Remember Manny, the woolly mammoth, and Diego, the saber-toothed tiger from Ice Age? Wouldn’t you love to see such creatures in real life? Too bad they’re extinct…or not?

Thanks to recent developments in biotechnology, the stuff of science fiction may soon become a reality through a fascinating process called ‘de-extinction’.

Recommended Video for you:

What Is De-extinction?

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) guidelines define de-extinction as the generation of proxies of extinct species that are functionally equivalent to the original extinct species, but are not ‘faithful replicas’. More simply put, de-extinction is like a ‘ctrl-Z’ (undo key) for extinct animals, but the resurrected animal is not an exact copy.

There are three primary techniques of de-extinction:

1) Back Breeding

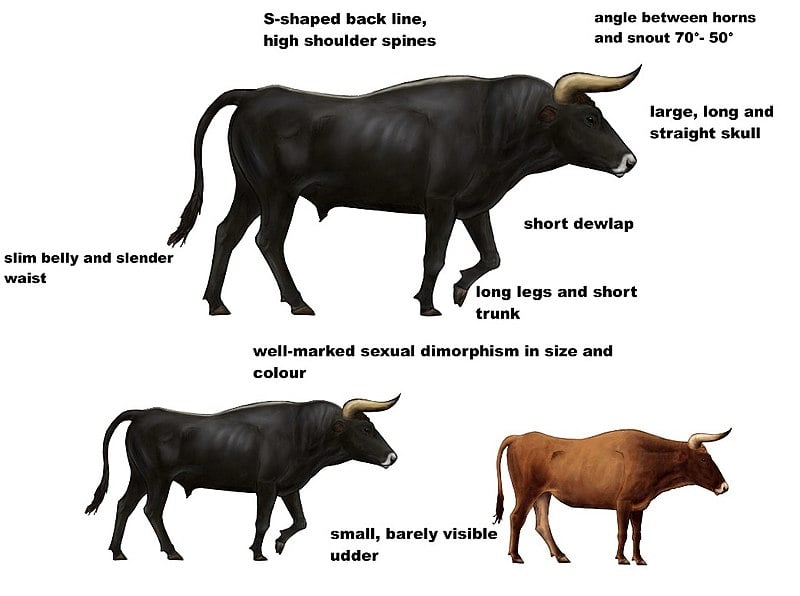

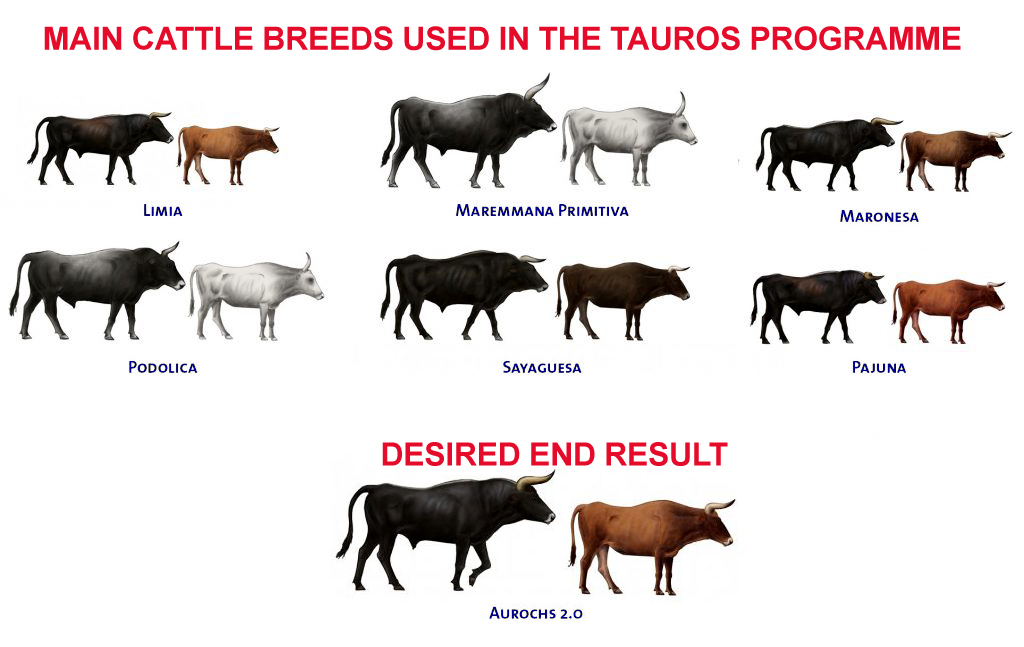

Existing species that have similar traits to the extinct species can be identified and selectively bred to produce offspring that more closely resembles the extinct species.

For example, the extinct aurochs, the ancestor of all modern cattle, are being brought back through the ‘Tauros Programme’. By selectively breeding existing cattle that closely resemble the auroch genetically, scientists hope to achieve an animal that closely matches Europe’s original wild auroch.

This is a very crude method, as compared to the other more complex de-extinction methods.

2) Cloning

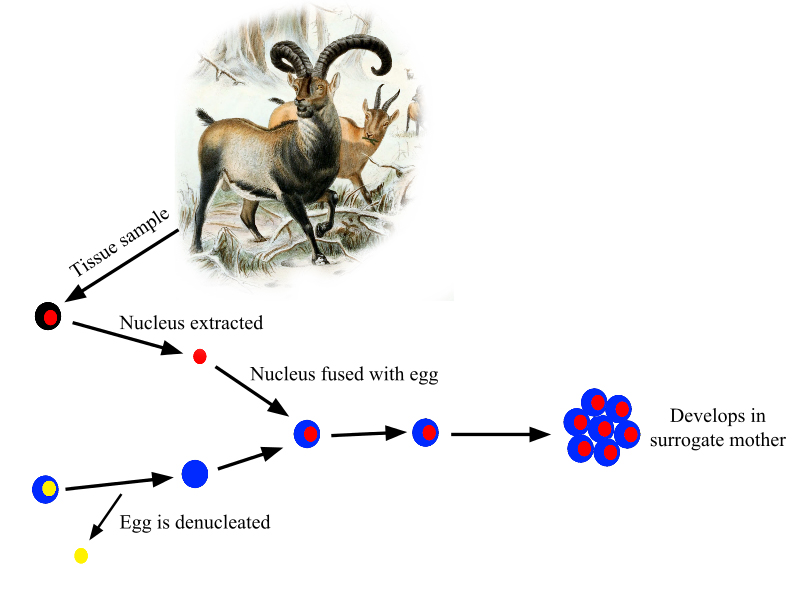

This one is exactly what you would imagine. A clone of an extinct animal is created by extracting the nucleus, which contains the DNA of the extinct animal, from its preserved cells. This DNA is then inserted into an egg cell (obtained from the animal’s closest living relative) that is devoid of its own DNA, i.e., a nucleus. This egg cell completes its development in the womb of a surrogate female and the offspring will be an identical genetic copy of the extinct species.

This method is only applied to animals that are either on the brink of extinction or have recently gone extinct, as it requires well-preserved eggs with intact nuclei. For example, this technique was used in 2003 to bring back a wild goat known as a bucardo (Pyrenean ibex), found in the Pyrenees mountain range in Europe, albeit it only survived for 10 minutes. The offspring couldn’t breathe due to a large, solid, extra lobe on one of her lungs. Unfortunately, the bucardo became the first animal to go extinct twice. However, this is the closest anyone has gotten to true de-extinction.

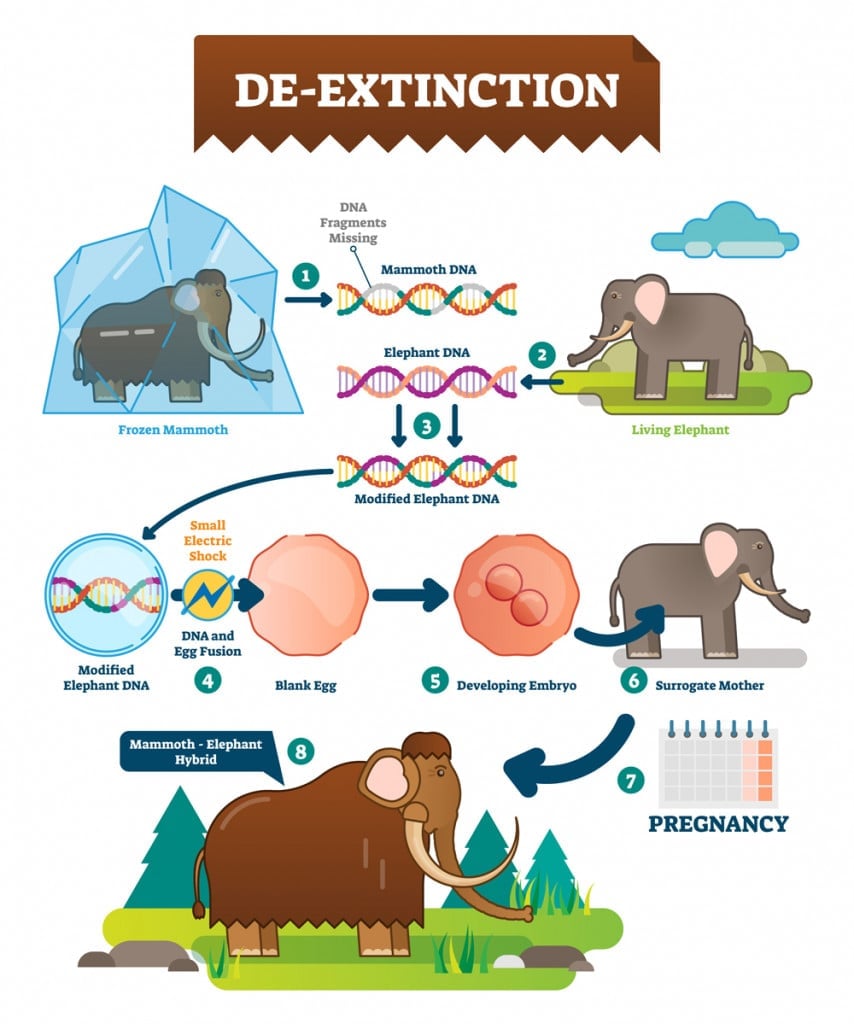

3) Genetic Engineering

This is the newest technique that has become available thanks to the advancements of modern technology. It uses gene-editing tools, such as CRISPR, to insert selected genes from extinct animals in place of those present in its closest living relative. The resultant hybrid genome is inserted into a surrogate.

The Harvard Woolly Mammoth Revival project is working to identify important genes required for adapting to the cold tundra climate. Once identified, these genes can be inserted into the Asian elephant genome. What they hope to achieve is a hybrid cell that has mostly elephant DNA, along with some mammoth genes. Hence, the result will not be an identical copy of a mammoth, but a hybrid elephant that is genetically modified to resemble a mammoth.

Why Bother With De-extinction At All?

If Jurassic Park is anything to go by, resurrecting extinct animals is a terrible idea. Thankfully, we don’t have to worry about dinosaurs running amok, as their DNA has disintegrated over the 65 million years since their extinction. DNA can survive for a couple of million years at best, under certain rare conditions, so it is possible to resurrect animals that have gone extinct within this timeframe, but does that mean we should?

De-extinction caters more to ecology than to tourism. According to ecologist Ben Novak, if a resurrected animal is always going to be a zoo animal then it shouldn’t be brought back.

Since all animals perform critical roles in their ecosystem, the void that their loss leaves can have detrimental consequences. Woolly mammoths, for example, were excellent gardeners. They stomped down saplings and spread seeds through their nutrient-rich dung across the then Arctic grasslands. Their disappearance was followed by a loss in biodiversity and transitioned the grassland to a cold, mossy tundra.

In 2016, ecologists from UCSB published guidelines for deciding which species should be revived to best impact the Earth’s ecosystems. The species selected were those that had gone extinct recently, were ecologically unique, and could be brought back in abundance. The species that met all 3 criteria were the Christmas Island pipistrelle bat (Pipistrellus murrayi), the Reunion giant tortoise (Cylindraspis indica) and the lesser stick-nest rat (Leporillus apicalis). However, no de-extinction programs have been initiated for these animals.

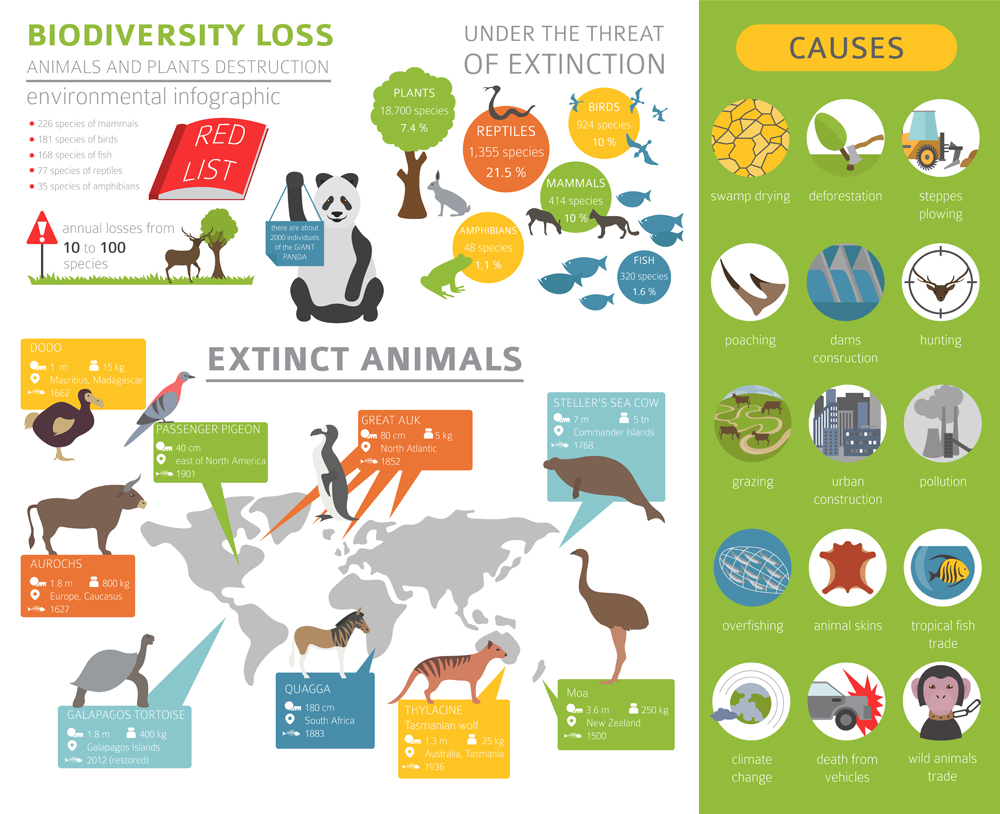

If nothing else, de-extinction is a golden opportunity to right our past wrongs. Humans are playing God by driving many of these animals to extinction due to hunting, polluting, and destruction of habitats. For instance, the passenger pigeon was abundantly found in North America, but around 1900, the last wild passenger pigeon was shot down by a boy with a BB gun. The Tasmanian tiger (thylacine) was a carnivorous marsupial native to Tasmania, New Guinea, and Australia, but went extinct in 1936 due to the combined impact of habitat loss, lack of prey, and hunting. The Pyrenean ibex (bucardo) was a European mountain goat that enjoyed thousands of years of peace before hunters arrived; the last one died in 1999.

Yet, there is some protest that de-extinction itself can also be interpreted as playing God. Those in opposition argue that since the resurrected animals can never be 100% identical to the extinct original, de-extinction does not truly reverse the ecological damage caused by humans. Still, others are concerned that by the time we successfully de-extinct a single species, the planet will have already lost a thousand others. Nevertheless, supporters of de-extinction continue to promote it as a solution to the planet’s ongoing mass extinction event.

However, Phil Seddon, who helped formulate the IUCN guidelines, believes that we should first protect the animals that are still living. Despite these concerns, Dr Axel Moehrenschlager, who worked with Seddon on the IUCN guidelines, believes that since these tools exist, they should be put to use, like with the Northern White Rhino, which is a functionally extinct (no living male) and critically endangered species.

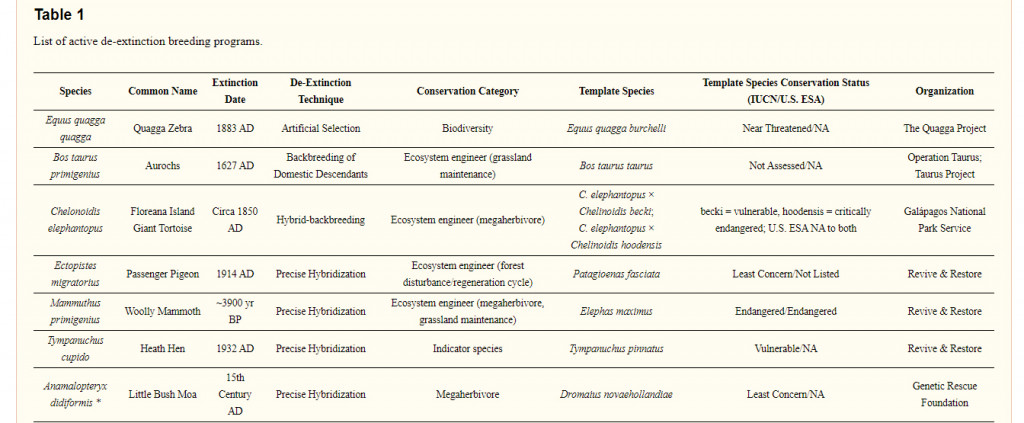

Although it has become a hot topic for debate, there are currently 7 active de-extinction projects worldwide: Aurochs (Bos taurus primigenius), the quagga (Equus quagga quagga), Floreana Island giant tortoise (Chelonoidis elephantopus), passenger pigeon, woolly mammoth, heath hen (Tympanuchus cupido) and an attempt to restore diverse moa species (order Dinornithiformes). If things go according to plan, we may be fortunate enough to see woolly mammoths in action once again!

References (click to expand)

- BBC - Earth - How to decide which extinct species we should resurrect - www.bbc.com

- Bringing extinct species back from the dead could hurt—not .... sciencemag.org

- Revive & Restore | Genetic Rescue to Enhance Biodiversity. Revive & Restore

- Bringing Them Back to Life - National Geographic. National Geographic

- Novak, B. (2018, November 13). De-Extinction. Genes. MDPI AG.