In the 1920s, wolves disappeared from Yellowstone National Park. Nearly a hundred years later, the rivers had changed their course. What happened?

The food chain and trophic cascade are two phenomena that we learn about in school. Though we may dedicate their definitions to memory, we’re never told of real-time consequences to the food web in real life.

One such cascade was observed in Yellowstone National Park, USA. During the mid-1920’s, a drive to eradicate wolves in the park (and across America) resulted in the river in the park changing its course. The connection is intriguing because wolves, as terrestrial carnivores, are not directly related to rivers.

So, what happened here?

Recommended Video for you:

What Is A Trophic Cascade?

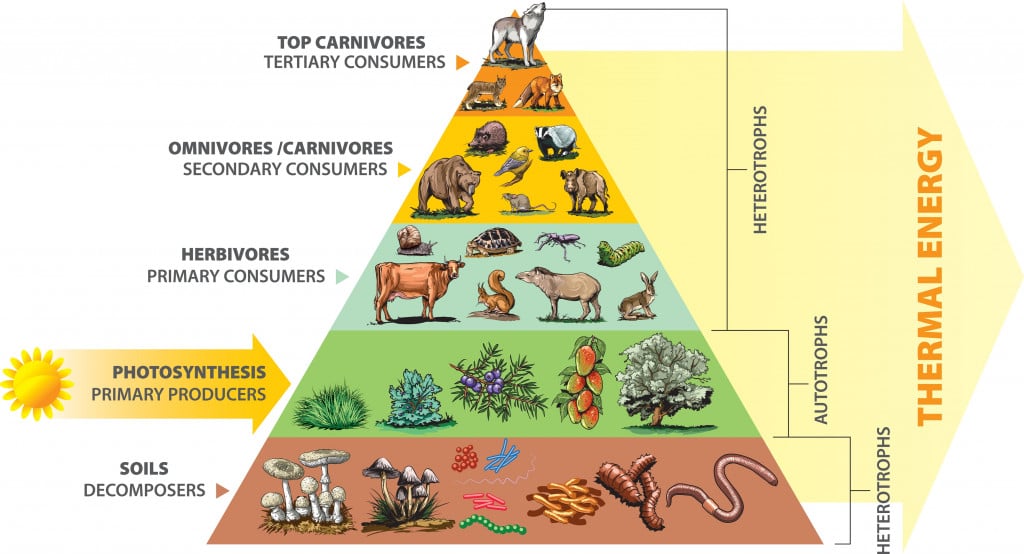

The food chain is the order in which living things are dependent on one another for the transfer of food and energy. Disrupting the food chain can lead to a hypothesized trophic cascade. It takes time for a trophic cascade to play out, but one clear case is what happened in Yellowstone National Park.

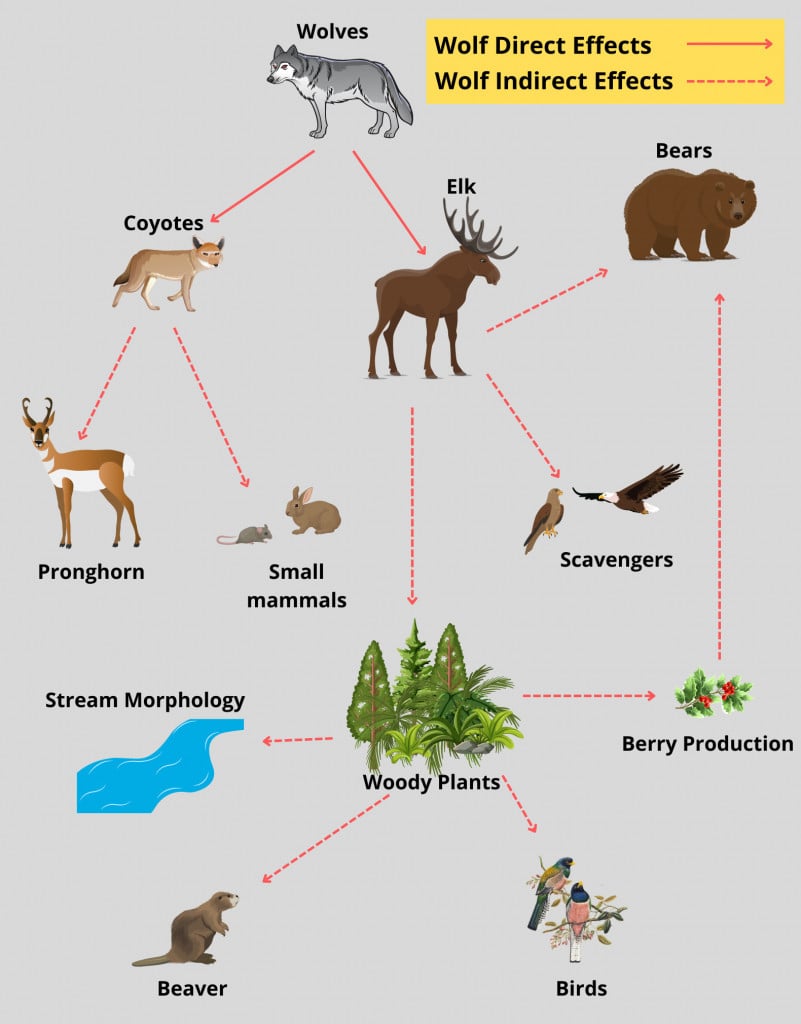

Due to the extermination of grey wolves, which occupied the top position in the food chain, the species present in the lower strata became uncontrolled and resulted in a population explosion, as well as the over-utilization of natural resources. The disaster caused by this unplanned removal took about seven decades to identify.

What Happened When The Wolves Disappeared?

The wolf extermination program began in the mid-1920’s in response to ranchers’ concerns about the safety of their livestock. Wolves are among the park’s top carnivores, preying primarily on elk (wapiti deer).

Because of the wolf extinction, elk predation pressure was reduced, and their population began to thrive and reach its peak in a few decades.

The increased population of herbivores put more strain on the vegetation, and as a result, the park’s grasses and saplings were stripped away. The loss of riverbank grasses and saplings was more pronounced, as the elk have a source of both food and water near the bank. Other species’ populations have also declined, due to the lack of available food. Scavengers were not getting carrion in the same form, as wolves would kill all year and leave plenty of scraps behind.

Why Did Beavers Leave Too?

The park also had a thriving population of beavers. Beavers feed on the rich nutrients found in new understory shoots of trees that were previously unavailable, due to elk overgrazing.

With the diminished foliage around the rivers, the beavers began to migrate from the river banks to other areas. With them went one of nature’s greatest engineering marvels—beaver dams. By retaining water, these beaver dams saturate the nearby soil, ensuring a steady supply of moisture for trees, even when there is no rain…

And Thus, The River Changed Its Course!

Without vegetation and no beaver dams near the riverbanks, the soil in the area began to erode. Seasonal flooding began, which caused rivers to meander away from their original course.

Changes in river course disturbs the water table and affects the vegetation growth of nearby areas. It also impacts the movement pattern of species from one side of the river to another.

Thus, a story that began with the removal of just one species from the top level of the food chain affected each and every link in a variety of ways, including an increase in elk population, a decline in biodiversity, habitat destruction for beavers, and, ultimately, a change in the course of the river.

We Reintroduced The Wolves. What Happened?

Soon after scientists discovered this trophic cascade in the natural system, 41 wolves were reintroduced to Yellowstone National Park after a nearly 70-year absence.

The wolves began preying on the abundant elk, and the elk gradually began to avoid open areas, such as river banks, out of fear of being killed. As a result, overgrazing near the river banks came to a halt, allowing new saplings to grow.

The beavers returned to the banks as well, building complex dams and providing adequate cover for smaller rodent species. The rate of soil erosion slowed, and rivers began to retrace their original path. As a result of reintroducing the top predator in the food chain, the entire ecosystem was restored.

Conclusion

Does this imply that substituting wolves for elk will solve the problem? No.

Wolves can be part of the problem too. As flexible predators, wolves prey on beavers and other animals that live and thrive on river bank vegetation. Too many predators, such as the wolves, could also change the course of rivers.

Nature’s processes are far more complex and result from numerous interactions between various biotic and abiotic factors. Scientists are still looking for other variables that can help restore the original form of Yellowstone National Park’s ecosystem.

Scientists admit that they still don’t understand all the factors that are causing the park’s surroundings to change, and as always, there is still a lot to learn!

References (click to expand)

- How Wolves Change Rivers | Beaty Biodiversity Museum. The University of British Columbia

- YELLOWSTONE-SCIENCE-24-1-WOLVES.pdf. The National Park Service

- Gable, T. D., Johnson-Bice, S. M., Homkes, A. T., Windels, S. K., & Bump, J. K. (2020, November 13). Outsized effect of predation: Wolves alter wetland creation and recolonization by killing ecosystem engineers. Science Advances. American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

- (2006) River channel dynamics following extirpation of wolves in .... Oregon State University

- Ripple, W. J., & Beschta, R. L. (2012, January). Trophic cascades in Yellowstone: The first 15years after wolf reintroduction. Biological Conservation. Elsevier BV.