Table of Contents (click to expand)

We have agricultural lands and gardens where we grow plants, and we keep animals as livestock and pets, but are humans the only species that do these things? Research has found that a few animal species do perform agricultural activities, the most sophisticated of which may be ants growing fungi gardens for food and rearing aphids like cattle.

Humans were once hunter-gatherers, constantly moving around in search of food. Then, about 12,000 years ago, we began the process of agriculture. Groups of humans settled in areas with fertile land and began selectively cultivating certain plants—crops—for food. These small settlements around the agricultural land slowly evolved into civilizations with cities and towns. The beginning of farming is a remarkable turning point in the history of humanity, and we’ve often used this advancement to set ourselves apart from other species.

However, we’ve discovered that we aren’t the only species farming on the planet! The practice is not being performed by some highly evolved primates or other food chain-topping group, but actually by a teeny tiny group of invertebrates—the small but mighty ANTS!

Ants started farming around 50 to 60 million years ago. Like humans, the insects also depended on their “food crops” and developed specialized agriculture worker groups within their colonies. Apart from ants, a few species of beetles and termites also perform such agricultural efforts, but this behavior is mostly exhibited by insects that live in groups.

There are two types of ant farming: some ants farm fungus, while others rear aphids.

Recommended Video for you:

Fungus Farms

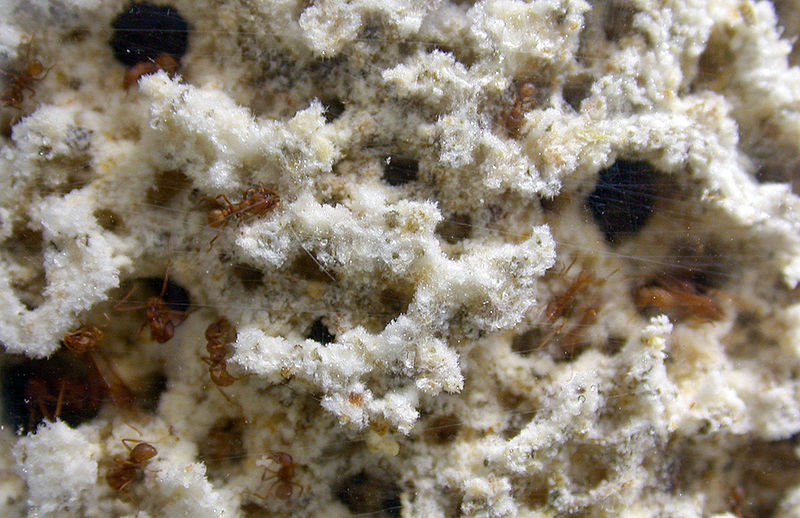

There is a well-known species of ants known as leafcutter ants that make their nests underground or within rotten logs. As their name suggests, the ants cut leaves into tiny pieces and then carry them to their fungus gardens. They also lick the leaves down, which is said to serve an anti-bacterial function.

Within their nests, they have an area demarcated to grow fungus—a fungal garden!

The ants drink the sap of plants with the fungus in them and then poop on the cut leaves. The poop contains fungal enzymes that break down the leaf matter and then fertilize the fungal garden.

The ants get their nutritious food in this creative way. Fungi produce enzymes that break down plant tissues, making it easier for ants to break down plant matter. For the fungi, it is an excellent chance to thrive on a leaf substrate without competition from other microbes. They also get protection from other microbes.

The fungal type grown by each species of ant is unique. When a queen ant leaves the nest to start a new colony, she carries a tiny bit of fungus along with her, just like your mom might give you a plant to take with you when you move out of the house!

Aphid Farms

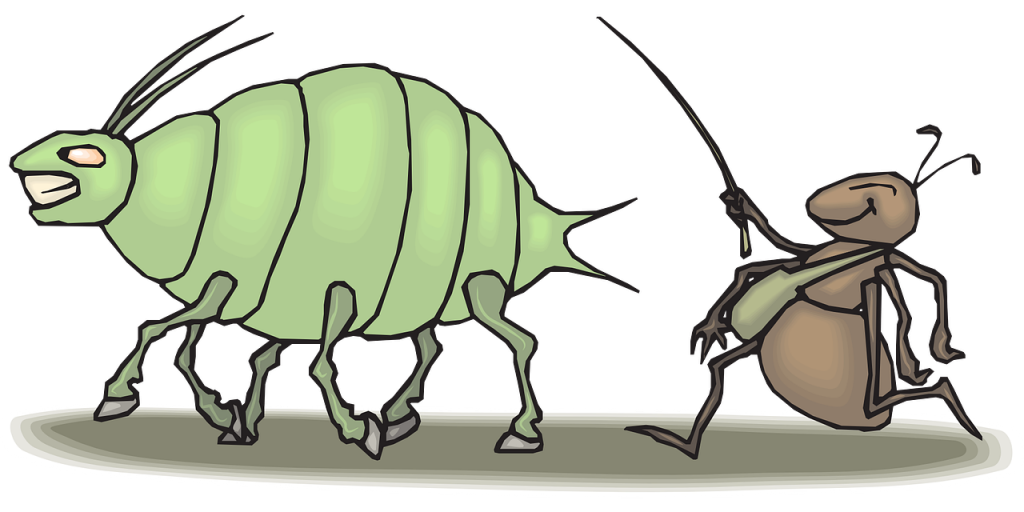

Aphids are members of the insect superfamily Aphidoidea. They are really small (smaller than ants), they live in groups, and are commonly called greenfly or antcow.

Aphids have long and thin mouth parts that they use to cut into the stems and tender parts of plants and then suck the juices out of them. Following this, they generate a sugary liquid called honeydew, which the ants love.

Ants house groups of aphids in their nests and treat them like cows. The well-fed aphids are stroked gently on their backs (a process called milking) by ants with their antennae. When ants do this, the aphids secrete honeydew, which the ants drink up eagerly.

The ants protect the soft-bodied aphids, as they have little to no defense capabilities, and the ants get a constant, energy-rich food supply in return. Certain chemicals secreted by ants have also been observed to have a tranquilizing effect on aphids.

At times, it has been observed that ants will take aphids to plants to feed and then herd them back to their nest. Not too different from what humans do with cattle, right?

They also removed dead or microbially infected aphids to keep their nests clean and safe. Again, when a queen ant leaves the nest, she will carry an aphid egg with her to start a new farm. Only ants from the taxonomic subfamily Formicinae keep aphids.

Conclusion

Such interactions, in which organisms belonging to different species have a long-term connection, are called symbiotic relationships. Here, both parties involved benefit from the other, making it a mutualistic interaction. Their relationship can either be obligate, as in the case of fungus, in which they cannot survive without each other, or it can be facultative, like with aphids, in which the interaction is optional. Such cooperative behavior in nature makes both species evolve more specializations, which makes them more efficient in building and maintaining that symbiotic relationship.

Do you think the relationship between humans and their cattle/crops is also mutualistic?

References (click to expand)

- Mueller, U. G., & Gerardo, N. (2002, November 18). Fungus-farming insects: Multiple origins and diverse evolutionary histories. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- North, R. (1997, October). Evolutionary aspects of ant-fungus interactions in leaf-cutting ants. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. Elsevier BV.

- Rønhede, S., Boomsma, J. J., & Rosendahl, S. (2004, January). Fungal enzymes transferred by leaf-cutting ants in their fungus gardens. Mycological Research. Elsevier BV.

- Denton, K., & Krebs, D. L. (2016). Symbiosis and Mutualism. Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science. Springer International Publishing.

- Andrews, E. A. (1930, October). Honeydew Reflexes. Physiological Zoology. University of Chicago Press.

- Nielsen, C., Agrawal, A. A., & Hajek, A. E. (2009, November 18). Ants defend aphids against lethal disease. Biology Letters. The Royal Society.

- CH Coulson. t ARIZONA AGRICULTURIST;. The University of Arizona

- (2005) Ecology and Evolution of Aphid-Ant Interactions - JSTOR. JSTOR

- Natural history and phylogeny of the fungus-farming ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Myrmicinae: Attini) - Natasha J. MEHDIABADI & Ted R. SCHULTZ - www.antwiki.org