Table of Contents (click to expand)

Song birds can sing because of a special organ called a syrinx. The reasons they sing are varied, from wooing a potential mate, to calling out alarms and even threatening away predators.

Every morning, the birds chirp and sing away outside our windows. A city’s soundscape is a cacophony of the sharp trill of bul-buls, the harsh cawing of crows, or the croo-croo of the detested pigeon. Outside of cities, you may hear the whining drawl of a peacock or even the tra-tra of a roller.

From May to July, you’ll hear young crows begging their parents for food, but this sound will disappear later in the year. Why do these calls change, and what do birds call for?

How do birds manage to make such a fascinating array of sounds? Why do these calls change, and what reasons do birds call for?

Recommended Video for you:

What Do Birds Need In Order To Sing?

All birds who can sing and call are part of the order Passeriformes. Passerine birds are, adorably, differentiated by the arrangement of their toes (which allows them to perch on branches, twigs and even electrical wires).

Bird song can be traced back between 66 and 69 million years ago, to the Cretaceous era. Ancestors of modern-day birds, likely dinosaurs, show evidence of being able to produce songs like birds.

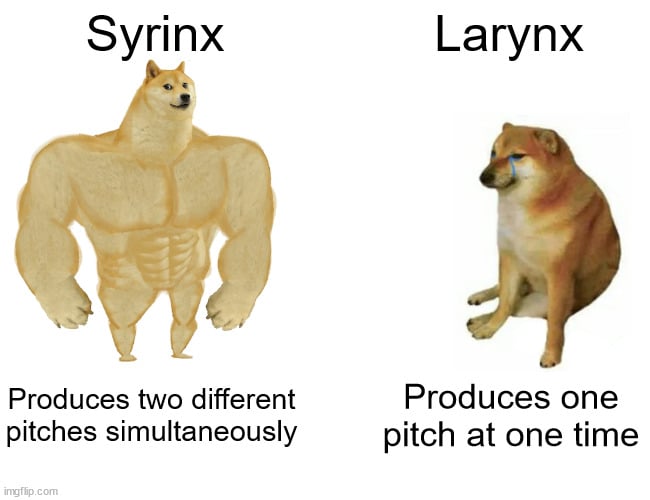

Humans and other mammals possess a larynx, otherwise known as the vocal cords or voice box. The larynx is a hollow tube that connects the throat (pharynx) with the respiratory system. It sits above the branch leading to the lungs, and allows us to speak and use our voices.

Birds also have a larynx, but unlike mammals, it is not responsible for vocalizations. Rather, the bird has a songbox, known as the syrinx.

The syrinx sits far lower in the avian respiratory system, at the branch before the lungs. Muscles on the left and right side of the syrinx can move independently, producing two separate sounds. Bird songs use this feature marvelously, with one organ producing a harmony of two instruments with two differing pitches and volumes.

You can learn more about how the syrinx works here.

The syrinx is thought to be a “key innovation” in the evolution of birds. After the first fossil record of the syrinx, birds rapidly diversified, forming thousands and thousands of species over the course of millions of years.

How Do Birds Learn To Sing?

Not all birds speak the same, or even similar languages. Some species possess repertoires of dozens of elaborate, minutes-long songs. Other species have just a handful of short calls. This influences how long it takes young birds of a species to learn the entire repertoire.

The development of bird songs in all species has been grouped into three phases : the sensory, sensorimotor, and crystallized phases.

Answering the question of how birds learn to sing is similar to understanding how children learn and speak languages.

During the sensory phase, young birds (particularly males) listen to as many birds as they can, learning how adults of their species sing. This is similar to how children babble and make noises when learning to speak. During the sensorimotor phase, they try out bits of songs and calls, playing with them and seeing how they fit together, like words falling into sentences. Finally, the song and repertoire is set in the crystallized phase, allowing birds to “speak” fully.

Some birds, like Zebra finches, learn only once in their life, with a single sensory and sensorimotor phase. Other birds, like canaries, learn throughout their lives, cycling through the three phases as needed.

Nature Or Nurture?

Is the bird song something that birds learn, or is there an innate song that comes out at adulthood?

Birds raised in isolation with only humans for company do develop some songs, but they are very different from the songs of other members of their species—short, stilted and abnormal. They also have some innate ability to recognize the calls of their species; after all, birds don’t learn the songs of other birds.

Where they grow up also matters. Bird songs, such as those of the white-crowned sparrow, seem to have regional variations. Isolated birds that hear songs from one dialect incorporate them into their own songs, even if they’re originally from a different region.

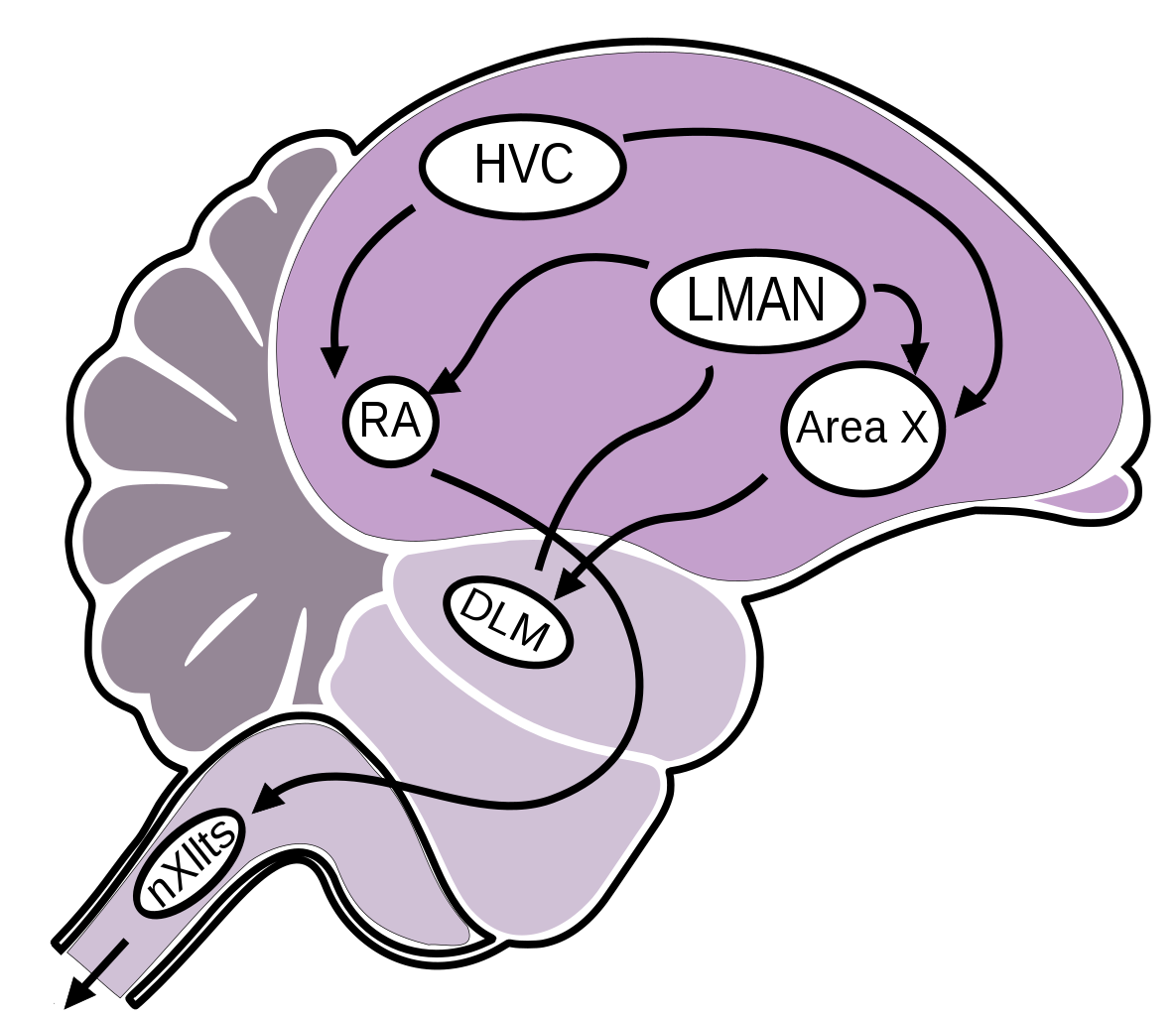

Researchers have also looked deep into the bird brain and isolated different regions responsible for controlling certain aspects of bird song.

In order to sing, birds need healthy brains and socialization with members of their own species, but why did the ability to sing songs give birds such an edge in fitness?

Why Do Birds Sing?

Bird song is an elaborate affair, requiring a separate organ, dedicated regions of the brain and a long learning period. All of this takes energy, so why does this pose a selective advantage? Why does evolution favor bird song?

One adaptation of bird song is alarm calls. Species such as Pygmy owls, Drongos, and American Robins forage in groups, calling out when larger predators circle close by so that the entire flock can escape. It is thought that alarm calls even evoke visual images of specific predators for the birds hearing them.

Social birds also use calls to communicate with each other. Babblers, crows and pigeons communicate extensively through calls. Japanese Great tits even seem to have syntax – when a song is played out of order, members of their species do not respond. Better communication means better resource sharing, predator avoidance, and overall health of the community.

Birds are most commonly believed to sing in order to gain mates. Female birds choose males with longer, more elaborate songs. The idea that this was a reflection of the suitability of the mate was proposed by Darwin, hundreds of years ago, but new evidence has arisen only recently. Birds with larger repertoires were likely fed more in their youth, with surplus energy not only for development, but for young birds to spend on calling and learning songs. There also seems to be a correlation between song complexity and the immune health of the bird singing.

In conclusion, the key innovation of the syrinx is what allowed birds to diversify and occupy the wide variety of habitats and environments they are found in today. Different species of birds learn bird songs differently, but all of them need members of their own species to teach them how.

Despite the complexity and energy-intensive nature of bird song, it can provide a wide variety of advantages to bird species. It can even help female birds choose better mates, leading to an eventual overall improvement in the fitness of the bird population.

Bird song is a commonplace phenomenon, and decades of research have begun uncovering just how and why this ear-pleasing tendency is so important for avian survival.

References (click to expand)

- Clarke, J. A., Chatterjee, S., Li, Z., Riede, T., Agnolin, F., Goller, F., … Novas, F. E. (2016, October). Fossil evidence of the avian vocal organ from the Mesozoic. Nature. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- The Development of Birdsong | Learn Science at Scitable. Nature

- Catchpole, C. K. (1987, April). Bird song, sexual selection and female choice. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. Elsevier BV.

- Suzuki, T. N. (2018, January 29). Alarm calls evoke a visual search image of a predator in birds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- Suzuki, T. N., Wheatcroft, D., & Griesser, M. (2016, March 8). Experimental evidence for compositional syntax in bird calls. Nature Communications. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- McCasland, J. (1987, January 1). Neuronal control of bird song production. The Journal of Neuroscience. Society for Neuroscience.