Table of Contents (click to expand)

Research has found that animals, other than humans, can perceive the stars and use their location in the night sky to migrate, find shelter, locate safe spaces for their dung balls, and even fly parallel to the ground.

It’s no secret that stars have guided humans since time immemorial, but do other species also use the starry sky as a compass?

Recommended Video for you:

Are Animal Eyes Built To See Stars?

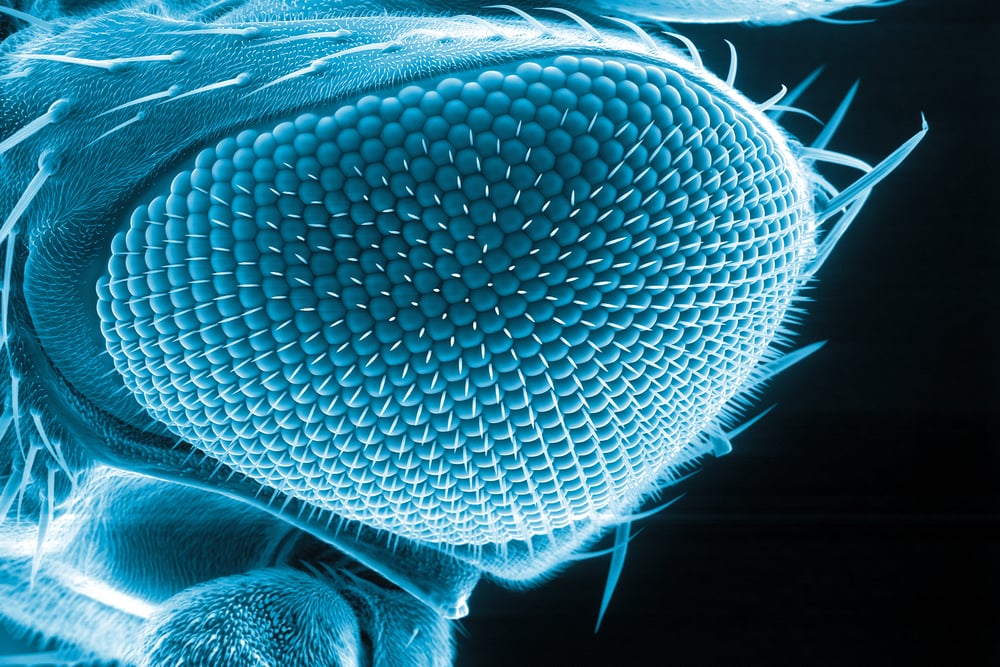

There are countless examples of how animals use solar navigation to migrate. However, utilizing stellar navigation requires these animals to own a set of eyes that are sensitive enough to adapt from viewing a single bright entity (the sun) to millions of dimly lit light sources (the stars). In other words, for any given animal, the light emanating from the stars is perceived to a much smaller extent than the region that illuminates a single light-sensitive cell in its eyes.

Large animals, such as mammals, cephalopods and birds, have eyes that use one lens to focus light on the retina to create a picture that is processed by the brain. Such animals are said to possess “camera eyes,” and they view the night sky just as we do. They see the bright stars first, but the fainter ones appear as their eyes get used to the dark.

However, for animals with compound eyes (like insects), each facet of their eye perceives light from many stars, eventually overlapping.

The kind of eye they have will dictate how an animal uses the night sky to navigate.

Migratory Birds

In 1967, Stephen T. Emlen, a renowned ornithologist, set up experiments with North American indigo buntings (sparrow-like songbirds) to prove that birds didn’t have any inbuilt clocks to migrate. He found that the birds use the night sky as their GPS.

First, he placed them in a man-made planetarium. To identify what exactly helped the birds with their direction, he started blacking out stars and constellation patterns one after another. The birds would fly in the direction they were supposed to until Emlen hid the stars in the vicinity of the North Star. The North Star maintains a relatively constant position in the sky; for that reason, sailors, pirates, and shipmen have relied on that star to guide them for centuries. Emlen confirmed that these birds similarly rely on the North Star. Without this star’s guidance, the birds would be thrown off their game—and off-track!

Since Emlen’s work was publicized, scientists have found other night-migrating songbirds, such as bobolinks, savannah sparrows, and garden warblers, that use stellar cues to navigate.

Seals

Like birds, seals are also known to follow individual bright stars in the sky. Seals travel long distances in search of food or to reach a preferred beach for mating or rest. Harbor seals (Phoca vitulina), placed in a floating aquarium, would learn the starry patterns that were projected and follow a bright star (like Sirius) projected above them.

Dung Beetles

With the simple motive of finding a dung ball and transporting it to a safe place, a nocturnal dung beetle must strategically position itself so that it rolls away from the dung pile in a straight line. Any zig-zags from its planned path can have it rolling in circles or remaining close to the dung pile, where other beetles might try to steal the dung ball that it worked so hard to gather.

Scarabaeus satyrus, a nocturnal species of the beetle family, orients itself using a variety of stars that constitute the Milky Way. Planetarium-based studies have shown that only when the entire Milky Way was visible would these beetles roll their dung balls in the proper direction. Selectively blacking out the stars or removing the Milky Way pattern from the sky would result in the adoption of a poorly oriented, circular path.

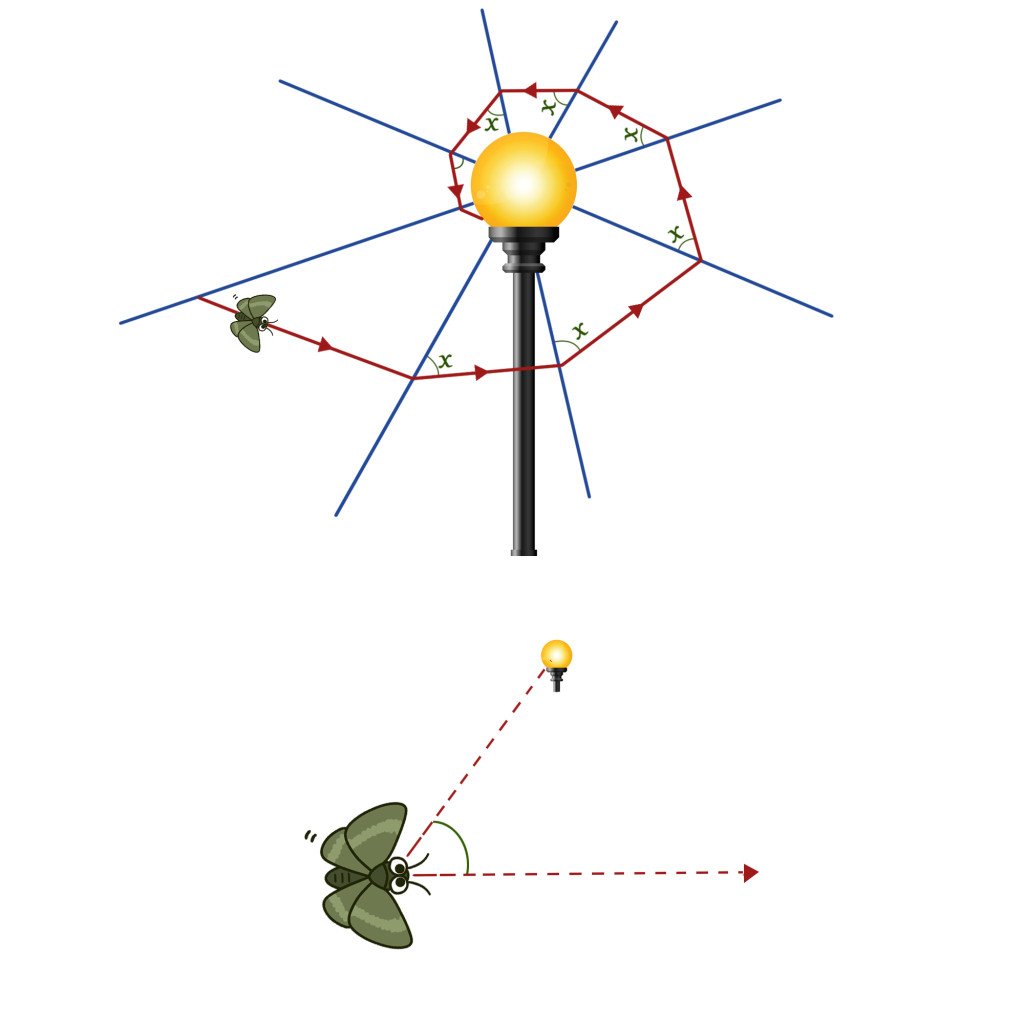

Moths

Moths are one of those species of insects that undertake migrations spanning hundreds to thousands of miles. These creatures will use the moon, stars, or any other celestial body as their steady light source, and relative to this, will position themselves at about a 90-degree angle before they can navigate. As a result of this orientation, they can fly more or less parallel to the ground.

Closing Thoughts

Experiments can only prove that animals use stellar navigation. How and why they do it remains extremely hard to decipher. Obtaining a navigational cue from a pattern of bright lights remains a mystery for many scientists today.

Even so, an animal that uses stars as a compass to move is likely to have developed this trait through many evolutionary steps that may have spanned thousands of generations. A brightly lit sky is important for such animals, but light pollution from cities and other urbanization events often obstructs the natural source of light from the stars. This could potentially disrupt the migratory patterns of various animals that employ stellar navigation, resulting in serious threats to their continued survival.

References (click to expand)

- Foster, J. J., Smolka, J., Nilsson, D.-E., & Dacke, M. (2018, January 24). How animals follow the stars. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. The Royal Society.

- Menz, M. H. M., Scacco, M., Bürki-Spycher, H.-M., Williams, H. J., Reynolds, D. R., Chapman, J. W., & Wikelski, M. (2022, August 12). Individual tracking reveals long-distance flight-path control in a nocturnally migrating moth. Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

- Sotthibandhu, S., & Baker, R. R. (1979, August). Celestial orientation by the large yellow underwing moth, Noctua pronuba L. Animal Behaviour. Elsevier BV.

- Foster, J. J., el Jundi, B., Smolka, J., Khaldy, L., Nilsson, D.-E., Byrne, M. J., & Dacke, M. (2017, April 5). Stellar performance: mechanisms underlying Milky Way orientation in dung beetles. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. The Royal Society.

- el Jundi, B., Warrant, E. J., Byrne, M. J., Khaldy, L., Baird, E., Smolka, J., & Dacke, M. (2015, August 24). Neural coding underlying the cue preference for celestial orientation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- Mauck, B., Gläser, N., Schlosser, W., & Dehnhardt, G. (2008, May 9). Harbour seals (Phoca vitulina) can steer by the stars. Animal Cognition. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Keeton, W. T. (1979). Avian orientation and navigation: a brief overview. British Birds, 72, 451-470.

- Horridge, G. A. (1977). The Compound Eye of Insects. Scientific American, 237(1), 108–121. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24954051

- Malmström, T., & Kröger, R. H. H. (2006, January 1). Pupil shapes and lens optics in the eyes of terrestrial vertebrates. Journal of Experimental Biology. The Company of Biologists.

- Shapiro, L. A. (2000, December). Multiple Realizations. The Journal of Philosophy. Philosophy Documentation Center.

- Dacke, M., Baird, E., Byrne, M., Scholtz, C. H., & Warrant, E. J. (2013, February). Dung Beetles Use the Milky Way for Orientation. Current Biology. Elsevier BV.

- ST Emlen. (1967) Migratory Orientation in the Indigo Bunting, Passerina cyanea. JSTOR