Table of Contents (click to expand)

Eagles have larger eyes, more visual receptors, and eyes that are wider set in their skull. This allows them to see a wider range of colors, acclimate to darkness quicker, and have a wider field of vision.

With visual acuity that is four to eight times stronger than humans, an eagle can spot its meal from 3 to 4 kilometers away, whereas human sight is limited to about 0.001 kilometers.

Having ‘eagle eyes’ would change the way you view the world—literally! From the curvature of the eyeballs to the number of cells in the eye, human eyes differ from eagle eyes in many aspects. Thus, to achieve an eagle’s point of view, there’s a lot we would have to change about our eyes!

Recommended Video for you:

Bigger Eyes

Our eyes are relatively small, when size-to-body weight ratio is taken into consideration. The same cannot be said about eagles. Morphologically speaking, our eyes would have to be 13 times larger than they are, to match an eagle’s eye-to-body weight ratio. Therefore, an eagle’s eye is literally bigger and better than the eyes of humans.

Natural selection has favored their eyes to an extent where they have actually impacted their brains (size-wise). Occupying close to half the space in their skull, eagle eyes are massive!

More Visual Receptors

An eye, in general, can be compared to a camera. The lens of a camera is analogous to the cone cells in a biological eye. These cones are present on a structure called the retina, which constitutes the light- and color-detecting cells.

At the very center of the retina, these cones are arranged closely together, forming a fovea. Anatomically comparing the eagle’s eye with ours, there is a massive difference that influences the way our eyes view the world. We have a fovea that has about 200,000 cones per millimeter squared of the retina. Since this area is highly concentrated with cones, it appears like a shallow crater.

However, the region of an eagle’s fovea is quite different. Eagles have approximately more cones than human foveae, and thus form a much deeper crater that is highly convex.

The central foveal region (with almost two million cones per millimeter squared of photoreceptors) gives the eagle sharper focus on objects. Moreover, each eagle eye will have two foveae; along with the deeper central fovea, raptors also have a shallow temporal fovea that allows them to see slow-moving objects (such as a crawling rat).

Just as increasing the number of pixels add clarity to a low-resolution image, a higher number of cones per eye can enable an animal to view its subject in better definition.

Wider Spectrum Of Colors

Another aspect where our vision differs from that of an eagle is the way we perceive colors. Eagles can view more colors than we’ve described on all the paint palettes in human history. They can see more shades, hues and lights, and distinguish between similar-looking colors in an exceptional manner.

Scientists used to believe that eagles could also see UV light. This capability may have evolved to make them better hunters. The urine of small animals, like rodents and other herps (ambhibians and reptiles), can reflect UV light. If and when they leave a urine trail, it becomes easy for the eagles to detect it, and narrow down their search area, especially in the dark.

However, recent research has revealed that raptors are more likely to be sensitive to wavelengths falling in the range of more than 400 nanometers (also known as the violet vision system) than the ultraviolet vision system of less than 400 nanometers.

The Power Of Accommodation

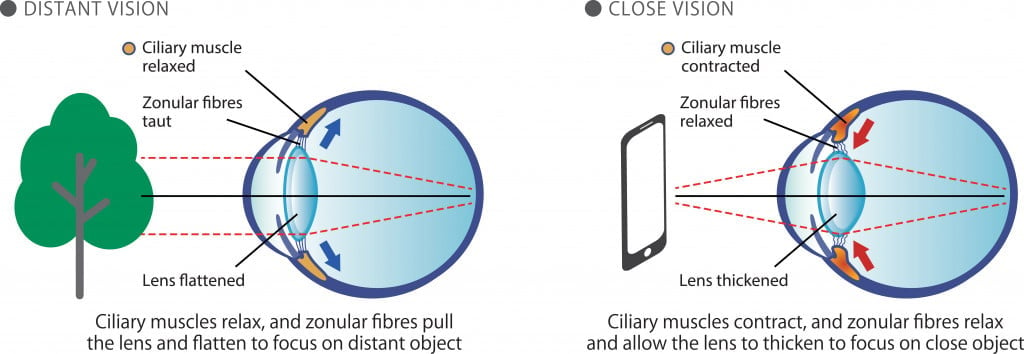

Eyes can view distant objects in both dark and light environments, owing to the lens’ ability to change shape.

Imagine you’re in a dark room when a bright light suddenly floods in. Everything in the room will look distorted and your eyes will take a moment or two to normalize. This adjustment that the eye must do, in order to perceive the object in its true form, is called accommodation.

The pupil, which is the central opening in our colored tissue, called the iris, is quite small when the eye is exposed to bright light. This regulates the amount of light coming in. However, the pupil must expand in a dark room, in order to let more light in.

Expanding and contracting the pupil helps us see and focus in changing light intensities.

In the case of eagles, not only do their lenses change shape, but their corneas (transparent part of the eye that covers the iris) do too. This gives them the power to see objects both near and far, and in a wide range of light intensities.

Larger Degree Of Field View

If you’ve seen an eagle, you’ll have likely noticed that their eyes are placed on either side of their heads. From the midline of their face, they are angled at 30 degrees. Our peripheral view is quite limited, and we’d need almost twice as large a field of view in order to compete with the large field view of an eagle.

The orientation gives them a 260-degree horizontal and 80-degree vertical view, an almost all-around panoramic view.

This, along with a major chunk of their brain being dedicated to processing visual cues, plays to their advantage, especially when they’re out to hunt—or are being hunted.

Closing Thoughts

So, is it possible for us to achieve the vision of an eagle?

The truth is, our eyes are physically incapable of viewing the world like an eagle. The dimensions and eye-to-head size ratio of humans makes it impossible to perceive faraway objects with the same clarity, color and visual acuity. Eyesight correction surgery, like LASIK, can enable us to see as clearly as a human eye possibly can, but surgeries to give us ‘eagle eyes’ would have to change the fundamental morphology of our eye.

Now, we might not be able to match the visual sense of eagles, but some humans do have better eyesight that others. In fact, in the 1840s, Australian aboriginal people did not need to use binoculars for distant viewing, while other non-aborigines did. Those people had an eyesight that was four times better than the rest of us!

Scientists are trying to mimic these special traits of eagle eyes in new technology, but it’s currently next to impossible to change your vision from 20/20 to 20/5. Guess we’ll just have to stick to binoculars for now!

References (click to expand)

- The Indigenous Eye Health Newsletter May 2015 - mspgh.unimelb.edu.au

- Potier, S., Mitkus, M., Bonadonna, F., Duriez, O., Isard, P.-F., Dulaurent, T., … Kelber, A. (2017). Eye Size, Fovea, and Foraging Ecology in Accipitriform Raptors. Brain, Behavior and Evolution. S. Karger AG.

- Jones, M. P., Pierce, K. E., Jr, & Ward, D. (2007, April). Avian Vision: A Review of Form and Function with Special Consideration to Birds of Prey. Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine. Elsevier BV.

- Duan, H., & Xu, X. (2022, January). Create Machine Vision Inspired by Eagle Eye. Research. American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

- Deng, Y., & Duan, H. (2018, December). Biological Eagle-Eye-Based Visual Platform for Target Detection. IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE).

- Five things you probably don't know about bald eagles. The Forest Preserve District of Will County

- Kellie, A., Dain, S. J., & Banks, P. B. (2004, June 1). Ultraviolet properties of Australian mammal urine. Journal of Comparative Physiology A: Sensory, Neural, and Behavioral Physiology. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- (1990) Human Photoreceptor Topography. christineacurcio.com

- What Gives Birds Their “Eagle-Eyed” Vision?. The University of Arizona