Table of Contents (click to expand)

Although Laika’s precise fate is unknown, many space experts believe that she passed away from overheating soon after the third or fourth orbit based on on-ground simulations, which means that she died five hours after the launch of the spacecraft.

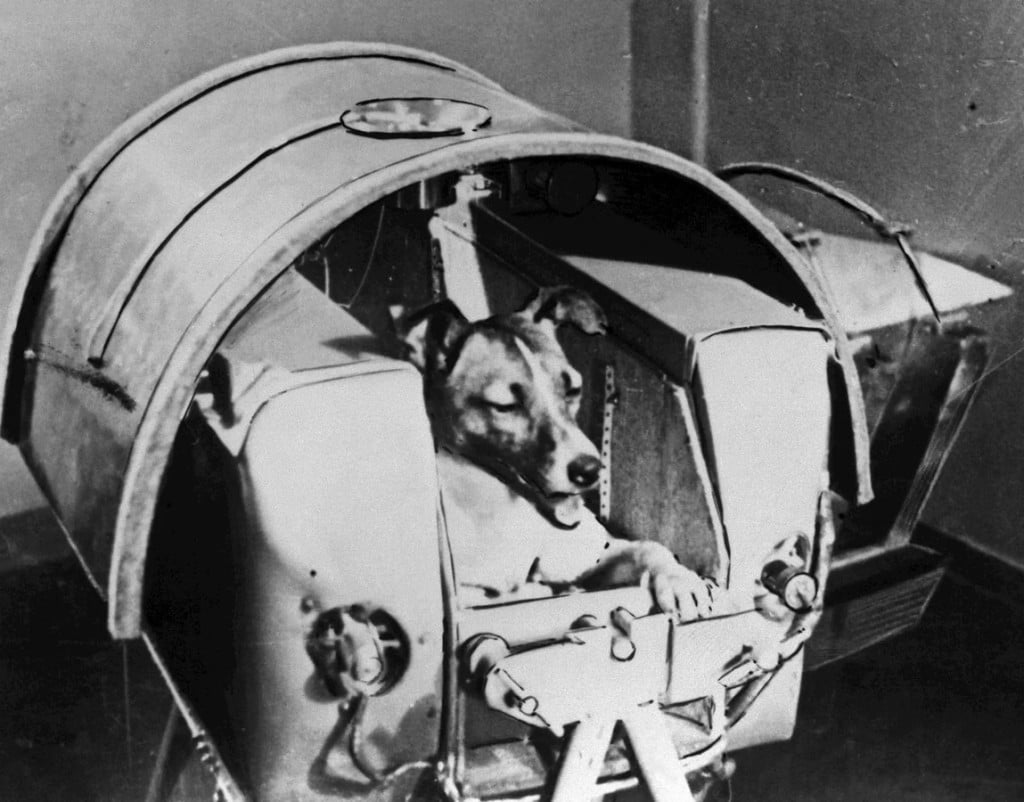

A stray dog struggling for food and shelter is suddenly en route to space. Unbelievable, right? Well, that’s the story of the first space dog, Laika, when in 1957 she set her paws aboard the Soviet spacecraft Sputnik-2.

Mankind has looked at the blue sky of day and the pitch dark of night in wonder of what lies beyond this planet. It is a vastness that raises a million questions and promises answers to them, if only we’re brave enough to venture out and find them. For a journey from the streets of Moscow into the endless darkness of the unknown cosmos, a dog was chosen to be the first non-human species to ever orbit the earth.

Recommended Video for you:

Why Did We Need Space Dogs In The First Place?

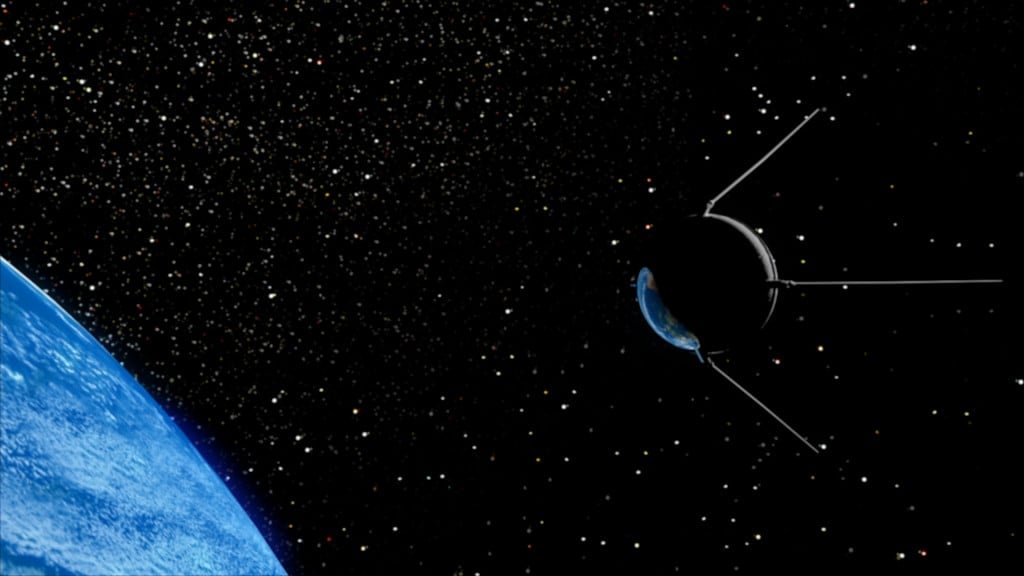

In the 20th century, the idea of space travel was only conceived by two countries: the United States of America and the Soviet Union (now called Russia). The tension of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union wasn’t just limited to Earth, but extended all the way to the moon and space.

Both centers of power wanted to establish their own dominion over spaceflight. It was a showcase of competence and technological intellect. It started in 1955, when America engaged in talks of putting artificial satellites over the earth for the first time. This started what would be called the “space race”.

However, for this space race to go from science fiction to reality, we needed to answer questions of how life would respond to the pressure, temperature, and vacuum of space.

Firstly, getting a rocket into space itself is risky. For a rocket to stay in space, the velocity of the spacecraft should be just enough or more to escape Earth’s gravity (called the escape velocity). If the rocket fails to reach such speeds, Earth’s gravity will pull the craft right back to the surface.

For this to happen, a rocket must accelerate to a velocity of 18,000 miles per hour, or 8046.72 m/s, in order to safely escape the gravitational pull of the planet.

The math was there, but the technology wasn’t.

The fastest rocket at the time could travel 3,100 miles per hour, but it wasn’t flown manually. The fastest any human had traveled in an airplane was 606 miles per hour. It was unclear how the human body would respond to such high speeds, unconventional pressures of acceleration, and risks from cosmic radiation.

The physiological concerns regarding high pressures, temperature and the vacuum were many:

- Ebullism (due to low atmospheric pressure, air bubbles form in tissue)

- Hypoxia (rapid de-oxygenation of the blood)

- Hypocapnia (reduction of blood CO2 levels)

- Decompression sickness (formation of nitrogen gas bubbles in blood and tissues as pressure goes from high to low)

- Extreme variations in body temperature.

- Cellular mutation due to radiation exposure.

It was dangerous, and unethical, to hurtle a human into space without developing the proper technologies to protect them.

Researchers and scientists considered the use of warm-blooded animals whose anatomy and physiology closely mirrored that of humans in order to address these problems, rather than endangering the lives of astronauts.

The Soviet Union used dogs as their animal astronauts, in contrast to the American Space Program, which used monkeys and chimps. Numerous space dogs actually traveled in rockets and soared into space to become astronauts. Many of the Soviet Union’s greatest achievements in the evolution of space exploration were made possible by those canine experiences. Animals would eventually be replaced by humans as astronauts, but not for another 15 years.

Requirements To Become A Space Dog

The Soviet Space Program intended to recruit its first group of space dogs, so it dispatched experts to Moscow. They chose canine mongrels who they believed would be ideal to withstand the harsh conditions in the prototypes, since they were already used to living in harsh conditions.

The 13–16 pound canine astronauts had to be small. Early Soviet rockets had extremely little space for passengers and lacked the capacity to move bulky objects. They also picked picked brightly colored dogs so the footage would be clearer. They also chose female dogs, as the space suit was made in such a way that made it simple for a female dog to urinate inside of it.

Along with all these requirements, the dog should also range in age from 2-6 years old.

Sputnik-2 And The Space Dog Laika

Laika was originally known as Kudryavka, or Little Curly. She was given the nickname Muttnik by American media as a play on the name of the spacecraft she was riding in—Sputnik.

Laika was trained to remain seated in the cabin throughout the flight and had been accustomed to the launch noises, acceleration, harness, and waste collection equipment. In order to radio the condition of Laika to Earth, a blood-pressure measuring device was surgically implanted across the carotid artery in the dog’s neck and silver ECG electrodes were installed in her chest for recording heart rate.

Sputnik-2 and the space dog Laika were both launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan on November 3, 1957.

Laika’s flight was the top story in practically every newspaper around the globe that week. The control station back on Earth received data about her condition from the Sputnik-2 capsule.

Laika’s heart rate was approximately three times higher than usual, according to heart-rate data, which was likely caused by the stress of the launch. However, the real issue was the heat, both from the Sun and the dog’s body. This worried Moscow experts from the very beginning of the mission.

It was discovered that the cabin warmed up gradually throughout the journey. Although Laika’s precise fate is unknown, many space experts believe that she passed away from overheating soon after the third or fourth orbit based on on-ground simulations, which means that she died five hours after the launch of the spacecraft.

Conclusion

Laika was the first animal in space, but she was certainly not the first animal used for space tests.

Albert, a rhesus monkey, reached a height of 37 miles in June 1948, but died when his parachute did not deploy. Between 1948 and 1951, the United States conducted six additional animal flights, with Albert’s being the first.

The Soviet Union successfully recovered two dogs named Deznik and Tsygan after launching them up to an altitude of 63 miles in August 1951.

It was in 1963 when a cat first went into space (Credits: Ideogram.ai)

It was in 1963 when a cat first went into space (Credits: Ideogram.ai)

Chimpanzee Enos was sent on the first U.S animal orbital flight and was recovered safely.

The only cat to have been launched into space is Félicette. She was launched as a member of the French space program on October 18, 1963. To track the cat’s brain activity, electrodes were placed in her head. Although Félicette made it through, she was put to sleep two months later so that her brain could be examined.

The first human to make it into space was Yuri Gagarin of the Soviet Union on April 12, 1961. This mission set the stage for later missions by various men and women from different nations. Gagarin gave a speech after his return in which he thanked everyone who had helped the mission be such a success. He made particular reference to the earlier voyage of the space dog Laika, whose name would live on in history books as the first living species on Earth to complete a true space flight.