Table of Contents (click to expand)

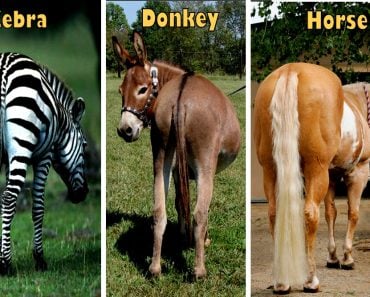

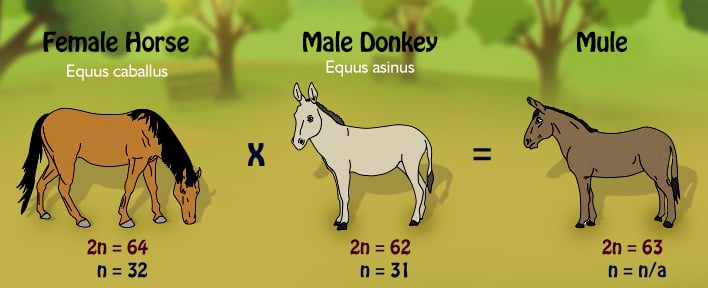

A mule is a hybrid of a female horse and a male donkey. Mules are infertile because they have an odd number of chromosomes. This is due to a horse having 64 chromosomes and a donkey having 62 chromosomes. This prevents the mule from creating gametes.

Mules have the best of both worlds. Being the hybrid offspring of a female horse and a male donkey, a mule has the sturdy make of a horse, and the muzzle and stout posture of a donkey. Though it shares many similarities with its parents, a mule can’t reproduce.

So, why can’t a mule have babies?

Recommended Video for you:

Mules Have Odd Number Of Chromosomes

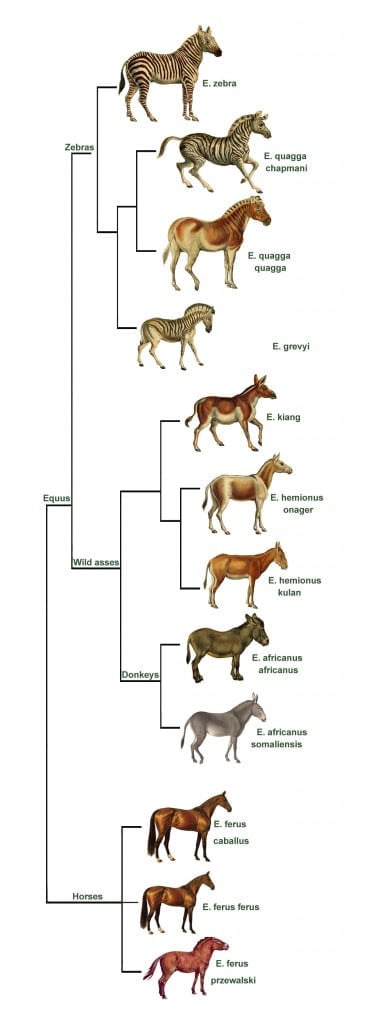

The term hybrid has multiple meanings in biology. One meaning is an interspecific hybrid: a union between two different species within the same genera. A mule is an interspecific hybrid of donkeys and horses, which are two different species, Equus asinus and Equis ferus, respectively, that both belong to the same genus Equus. The two species branched off from their common ancestor about 4-5 million years ago.

Over those 4 million years, the genetic makeup of horses and donkeys changed significantly. One difference is the number of chromosomes. Donkeys have 62 chromosomes, while horses have only 64 chromosomes. When a female horse and a male donkey mate, the mule offspring gets 32 chromosomes from its mother (horse) and 31 chromosomes from its dad (donkey).

Unequal chromosomes don’t constitute a good recipe for an organism. Under normal circumstances, which is to say, when individuals from the same species mate with each other, both the mother and the father give the same number of chromosomes. Thus, when two horses mate, both the mother horse and the father horse each give 32 chromosomes, which totals to the normal 64 chromosomes of a horse. The same is true for when donkeys mate.

Besides not having the same number of chromosomes, horses and donkeys also don’t have matching genes. Members of the same species have similar genes located in the same position on a chromosome. These genes contain information on how to “make” the organism and both pairs of chromosomes work together. Horse and mule DNA don’t quite match up in every regard.

Mules Sex Cells Can’t Perform Meiosis

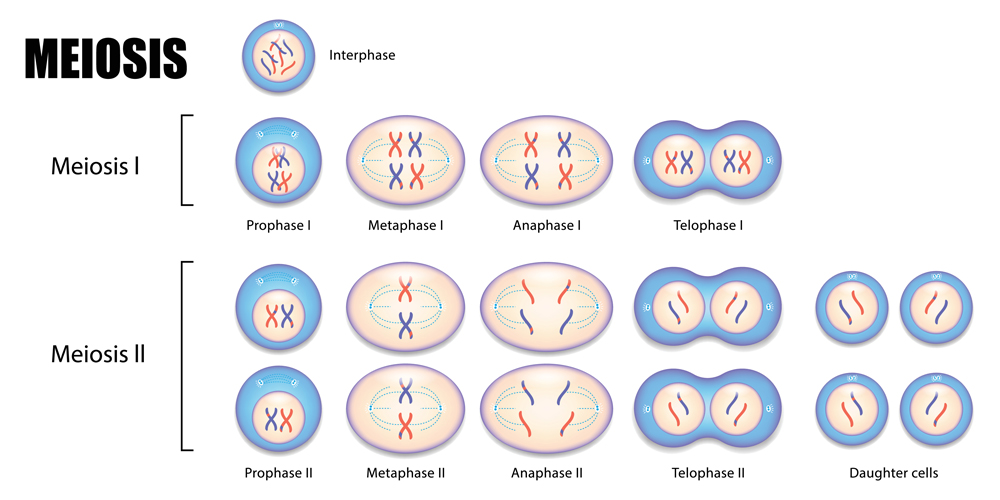

For a male and female mule to produce their own baby mules, the adults would have to produce gametes. Gametes, eggs and sperm, are created by a type of cell division called meiosis. During meiosis, diploid cells (normal pairs of chromosomes) divide into haploid cells (only half the number of chromosomes). Thus, a horse sperm or egg would contain 32 chromosomes, half of the normal 64 chromosomes of a normal horse cell. The idea is to halve the chromosome number so that when a sperm and egg fuse, the embryo will have the normal number of chromosomes.

In order to halve the chromosome number, the cell undergoes two rounds of cell division. In the first round, the DNA amount doubles and the cell divides. For this stage to occur, the doubled DNA must align itself with its matching pair, which is then seperated in the subsequent steps to create a haploid cell.

In sterile hybrid animals, like mules, this process can go wrong in several different places. For one, chromosomes fail to align properly in stage one of meiosis, perhaps due the mismatch between horse and donkey chromosomes. Without the DNA pairs matching, the rest of meiosis does not happen, which means that there are no viable eggs or sperm.

Besides the differences in DNA sequence, the mule also has a lonely horse chromosome. This extra chromosome, some research conjectures, might be another reason most mules are infertile.

Although the genetic and molecular mechanisms of mule sterility are still elusive, scientists have found genes which might be involved. Several genes on the Y chromosomes involved in male horse and donkey sperm genesis are disregulated in mule testis.

The Rare Fertile Female

Interestingly, there is anecdotal evidence of female mules conceiving, and occasionally, successfully giving birth to a mule foal. Many of these cases are simple errors. Female mules might “kidnap” or “adopt” the colt of a horse or a donkey, or a breeder might simply make a mistake.

There are very few actual cases of female mules giving birth. In cases when a donkey is usually the sire, the colt has the chromosomal profile of a mule, which is to say, it has a chromosome number of 63. In these super rare cases, a successful egg is produced by abandoning the paternal set of DNA, passing on only its mother’s lot. This means that the female mule’s child is also its own mother’s half sister. If that isn’t strange, I don’t know what is.

A Final Word

Just like mules, there are countless other hybrid animals that perplex scientists with their existence. Within the Equus genus, there is the hinny, zeedonk, and zorse, and just like the mules, they too can’t breed. Studying hybirds gives scientists a unique opportunity to peer into how nature works, by observing the anomalous.

In the early 2000s, the first mule was cloned; this was the first success after about 305 failed attempts. Cloning mules and other domestic animals help scientists understand the nitty-gritty of how cells function and grow. These efforts, scientists hope, will help conservation efforts to protect endangered species, including zebras.

For most of us, mules are as outdated as the earliest Nokia phone, but their contribution to human civilization has been important. And even in their hybrid infertility, they continue to help science understand and potentially save other spieces on this planet.

References (click to expand)

- Keefer, C. L. (2015, July 20). Artificial cloning of domestic animals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- Pearson, H. (2003, May 30). Mule cloned. Nature. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Jones, W. E., & Johnsen, D. W. (1985, January). A fertile female mule. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science. Elsevier BV.

- TAYLOR, M. J., & SHORT, R. V. (1973, March 1). Development Of The Germ Cells In The Ovary Of The Mule And Hinny. Reproduction. Bioscientifica.

- Chandley, A. C., Jones, R. C., Dott, H. M., Allen, W. R., & Short, R. V. (1974). Meiosis in interspecific equine hybrids. Cytogenetic and Genome Research. S. Karger AG.

- Steiner, C. C., & Ryder, O. A. (2013, April 22). Characterization of Prdm9 in Equids and Sterility in Mules. (P. Michalak, Ed.), PLoS ONE. Public Library of Science (PLoS).