Flightless birds tend to disappear soon after human settlements arrive. Some species have been hunted to extinction, while others have had their habitats destroyed.

When you think of birds, you probably peg them as masters of flight, but when we rewind to the age when dinosaurs went extinct, the birds that existed back then didn’t soar quite so high. Instead, they kept their heads down, grazing and running free on the land.

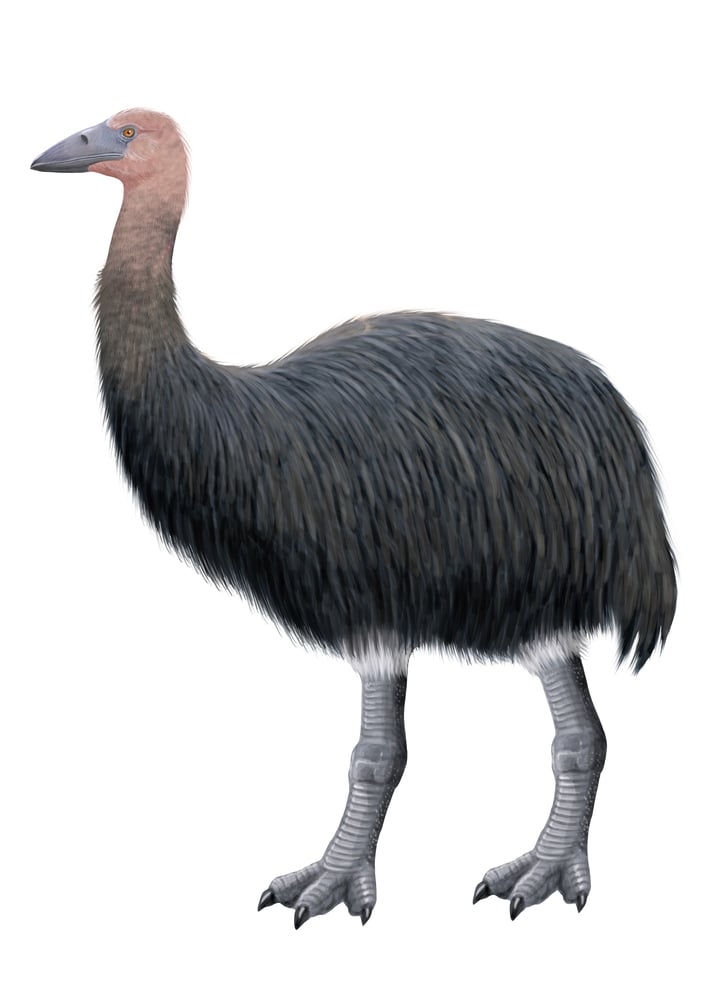

Grounded birds were not as rare as they appear to be today. In fact, flightless owls, ibis, woodpeckers, finches and many more were a common part of the landscape. They were well and truly alive, but are now sadly gone. There was one bird that outlived them all. True to its name, the elephant bird, weighing in at about 270 kilograms, was the heaviest bird known to science.

It’s surprising to think that size and strength wasn’t enough to keep these flightless birds alive. From large behemoths like elephant birds to small, odd-looking birds like dodos, they all faced the same unfortunate end.

Although natural events like infamous ice ages and volcanic outbursts cannot be entirely ruled out, it seems like more than a coincidence that these species disappeared shortly after humans encroached on their homes. It’s very likely that our ancestors exterminated them, either to fill their bellies, clothe their bodies or decorate their homes.

Recommended Video for you:

Could The Skies Be A Safety Net?

In the case of birds, it definitely can. Research suggests that flightless birds, or ratites, having lost their ability to fly, have been and remain more prone to going extinct than volant (flying) birds.

Humans are likely to blame for the long list of 581 bird species that have vanished over the past 126,000 years. Of these, 166 possessed wings that were too weak to fly. Ratites were widespread, so if their numbers weren’t decimated by humans, we’d still share this world with more than 150 flightless bird groups. Unfortunately, as it stands, only 60 of these species remain, including ostriches, rheas, kiwis and emus.

Not-so-safe Islanders

One study found that the percentage of extinction for volant birds was comparatively much lower than that of their flightless cousins. In ratites, 73.5% of the birds have gone extinct across the globe. However, the odds of them going extinct tripled if they lived on islands, rather than a non-island setting. 30% of the ratites are now extinct on mainlands, while a whopping 82.7% of island-bound species are now extinct.

Many islands worldwide had a good number of flightless birds. Ecologically speaking, they occupied a place in the ecosystem that would normally be filled by mammals. However, this dynamic changed when human settlements appeared. These flightless and naïve birds, who knew nothing about fearing mammals, stood no chance against humans and their non-native pets.

Some island hotspots where flightless birds were prevalent include New Zealand, with 26 species, and Hawaii, with 23 species, all of which are now extinct.

Lacking a crucial defense strategy, such as flight, ratites died out due to easy and opportunistic predation. Human hunters, along with rats, cats, dogs, pigs, etc, led to a severe decline in their population. Some birds that were able to evolve into better runners used that skill to flee from predators and managed to survive.

How Did Different Flightless Birds Go Extinct?

Dodos

These stocky little birds are reputed for being quite dumb, and for good reason. Hunting them was a piece of cake, as they had no idea they had a target on their backs. Now extinct, dodos once thrived in the forests of Mauritius. But when the Portuguese and Dutch discovered this island, it was a death knell for these birds. The pigs and rats that the humans brought ate the dodo’s eggs, making reproduction almost impossible.

Ecosystems quickly declined due to deforestation and urbanization. Thus, the dodo went extinct within a century of being discovered, wiped from the face of the earth in less than 100 years.

Moas

The moas were the last of the giant species to vanish. A group of people known as the Māori were the first settlers of New Zealand. Between 1250 and 1350, the ancestors of the Māori hunted all of the 11 known Moa species to extinction. They used its eggshells as water carriers, while the bird’s meat and eggs would feed the village. Additionally, spears, hooks and ornaments were made by utilizing the Moa’s bones. When a species is hunted during all of its life stages, it has almost no chance of survival.

Aepyornis hildebrandti, or the elephant bird, lasted in Madagascar until about 1,500 years ago, making it the longest-lived bird species. This giant bird finally fell victim to deforestation and hunting, as a single Elephant bird egg would equal about 160 chicken eggs.

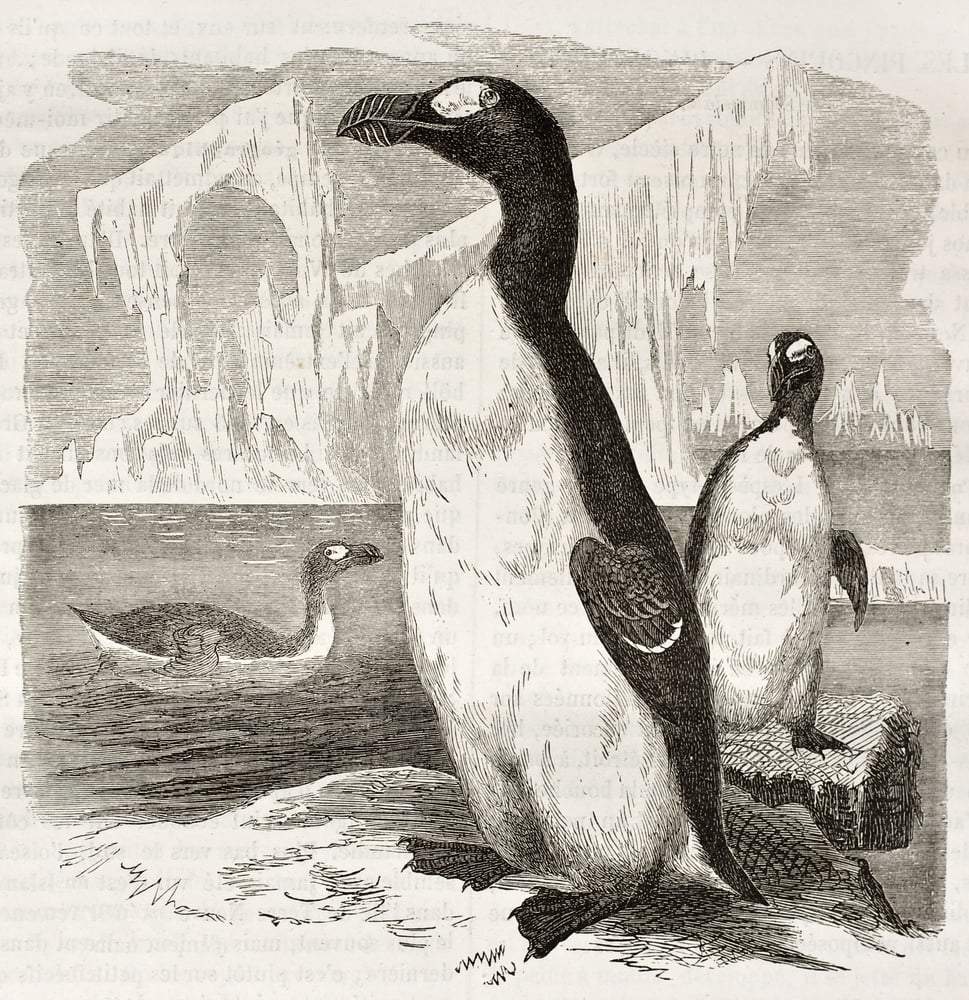

Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis)

This flightless seabird’s defenselessness led to it going extinct in 1844. Having occupied the North Atlantic coasts in the 1800s, they were captured in large numbers and slaughtered for food or bait.

On a side note, about 80 great auks and their eggs line the shelves of museums today.

Will Present-day Ratites Face The Same Fate As Their Ancestors?

Time seems to be catching up to flightless birds, namely penguins, rheas, ostriches and cassowaries. In addition to those that have already gone extinct, more than 50% of surviving ratites have been listed as threatened or vulnerable, and about 20% face the threat of endangerment. Thus, 80% of the flightless birds still alive today face an uncertain future. Humans could seek redemption by using conservative measures to save the dwindling populations of flightless birds, but that requires will that we often lack.

A Final Word

It’s ironic that the evolution of flightlessness, which developed in response to an environment without predators, became the very reason these birds were so easily targeted.

Flightless birds, in particular, are more vulnerable to extinction, as they lack an essential defense to escape predators. Especially for those thriving endemically on remote islands, extinction seemed like a distant threat. Little did they know that foreigners like humans, rats and pigs would rapidly lead to their absolute destruction.

References (click to expand)

- A Vanishing Avifauna - ARLIS. arlis.org

- Sayol, F., Steinbauer, M. J., Blackburn, T. M., Antonelli, A., & Faurby, S. (2020, December 4). Anthropogenic extinctions conceal widespread evolution of flightlessness in birds. Science Advances. American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

- Sayol, F., Steinbauer, M. J., Blackburn, T. M., Antonelli, A., & Faurby, S. (2020, December 4). Anthropogenic extinctions conceal widespread evolution of flightlessness in birds. Science Advances. American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

- Turvey, S. T., & Cheke, A. S. (2008, June). Dead as a dodo: the fortuitous rise to fame of an extinction icon. Historical Biology. Informa UK Limited.

- Serjeantson, D. (2001, January). The great auk and the gannet: a prehistoric perspective on the extinction of the great auk. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. Wiley.

- Fossil dung reveals where ancient moa ate - ABC. The Australian Broadcasting Corporation