Table of Contents (click to expand)

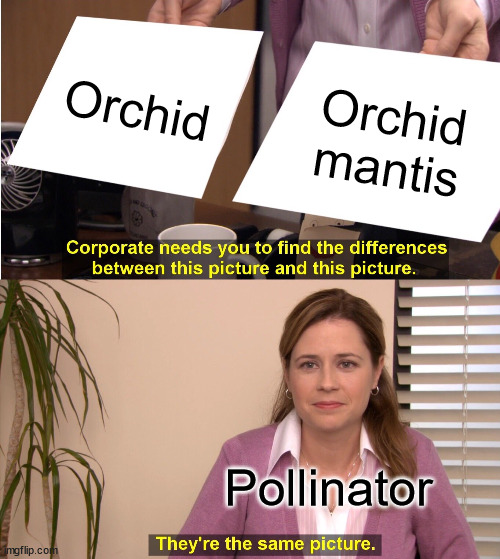

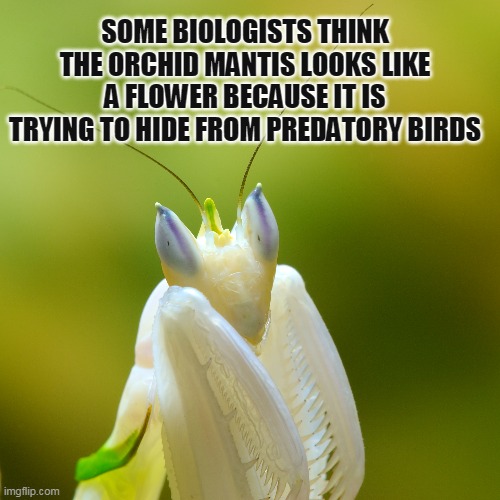

Orchid mantises are thought to look like flower orchids, but biologists think that the mantis might be doing more than simply mimicking orchids.

What do criminals, celebrities and spies all have in common? They use disguises to evade the cops or the paparazzi or other fellow spies. You can add to that list the orchid mantis’ masterful deception.

The Orchid mantis, Hymenopus coronatus, is a kind of praying mantis. However, unlike the green Master Mantis in kung fu panda, and most other praying mantises, which are green or brown, an orchid mantis’ exoskeleton is colored with vibrant hues like those of the orchid flower.

Of the six legs of a praying mantis, the four hind legs have a ‘femoral lobe’, which means they have a flap-like extension. When the mantis does a sort of crouch and spreads out its hind legs, those femoral lobes look like an orchid’s petals.

The Australian journalist James Hingsley famously mistook the mantis for an orchid. In 1879, while returning from a trip to Indonesia, he noted that an orchid devoured an insect whole. It was only later, in 1972, that scientists identified the hungry culprit as a mantis, and not an actual orchid. Since then, scientists have wondered why this praying mantis has adopted a full-time floral garb.

Recommended Video for you:

Predatory Strategy

Praying mantises are carnivores. They prey on a variety of animals, from small birds, such as hummingbirds and sparrows, and lizards to other insects, including other praying mantises. Infamously, the female eats the male while they copulate, if she gets hungry enough, that is. In the case of one species, the female decapitates her mate because it actually makes the mating more efficient!

Most praying mantises are either green (like the Chinese mantis, Tenodera sinensis) or brown (like the large brown mantis, Archimantis latistyla), which helps them blend into the foliage as they hunt down their prey.

On the other hand, the orchid mantis’ appearance allows them to stand out, rather than blend in. The white with blushes of pink is promiscuous, tempting unsuspecting pollinators like bees with the hopes of bountiful pollen. Instead of taking home dinner, the pollinators end up as dinner themselves!

In fact, the mantises perform a flower’s functions better than the flower itself. A study published in 2014 provided the first evidence for this. In fact, they found that pollinators were drawn towards the orchid mantis more often than they were to the orchid.

Interestingly, orchids are innocent of deception. The bee orchid looks and smells like a female bee (Eucera spp). A male bee who’s looking for a mate will mistake the orchid for a female bee and try to mate with it. In this process, the orchid’s pollen will get deposited on the male, who will then get fooled by another orchid, where the male bee will deposit the pollen. The poor male bee gets no reward for his effort.

Now, while we call them orchid mantises and they generally resemble orchids, the evidence proving this isn’t convincing. Nature has many pink and white flowers on offer, so the orchid mantis could just be mimicking “a general flower”.

This may actually give the orchid mantis another advantage. Since it could look like any generic, bilaterally symmetrical flower, pollinators don’t associate the orchid mantis with danger. The orchid mantis can continue to allure and pollinators will continue to be allured. This is perhaps the most successful marketing strategy the natural world has to offer.

This behavior is called floral mimicry, where an organism mimics the appearance of a flower to lure in another organism for their benefit. Floral mimicry is widespread among plants, such as the orchid’s tactics, but it hasn’t been conclusively noted in animals. The orchid mantis is one of the first examples of an animal mimicking a flower.

Hiding From Predatory Birds

Some biologists think that the orchid mantis’ appearance could have evolved from a need to hide from avian predators, rather than to allure prey.

Some research suggests that the larger female’s patterns gave it a predatory edge, while the smaller male’s patterns evolved to hide from predators, such as birds. Others say that there isn’t enough evidence for the former claim.

If the orchid mantis was mimicking a flower as a predatory strategy, its success would depend on the flower. If you exposed bees to enough orchid mantises, they would eventually get the idea that they shouldn’t sit on any white and pink flowers. However, that hasn’t been shown experimentally.

A Final Word

Biologists are still debating over whether these mantids look like orchids or general flowers. Many argue that, based on technical grounds, the trait should merely be called food deception, as opposed to mimicry, if the orchid mantises aren’t actually mimicking a single orchid species. Furthermore, juvenile orchid mantises appear more flower-like than adults, which puts into question whether the insects are mimicking orchids.

Many other “flower mantises” use their floral traits to hide amongst flowers, in ambush, awaiting their unsuspecting victims. They resemble inflorescences not to attract, but rather to hide from their prey. Other insects, like flower crab spiders and assassin bugs, employ a similar strategy, using flowers to blend into their surroundings.

One reason we’re still in the dark about orchid mantises is because they’re rarely spotted in the wild. Most of these studies were performed on lab-bred orchid mantises under laboratory conditions. And if there is one place that can’t capture the dynamism and mystery of nature, it is the controlled environment of a laboratory!

References (click to expand)

- O’Hanlon, J. C. (2016, February). Orchid mantis. Current Biology. Elsevier BV.

- O’Hanlon, J. C., Holwell, G. I., & Herberstein, M. E. (2014, February 1). Predatory pollinator deception: Does the orchid mantis resemble a model species?. Current Zoology. Oxford University Press (OUP).

- O’Hanlon, J. C., Holwell, G. I., & Herberstein, M. E. (2014, January). Pollinator Deception in the Orchid Mantis. The American Naturalist. University of Chicago Press.

- de Jager, M. L., & Anderson, B. (2019, May 11). When is resemblance mimicry?. (T. Houslay, Ed.), Functional Ecology. Wiley.