Phosphorus is a non-renewable resource; it is estimated that with the current rate of phosphate mining and phosphorus use, we will run out of phosphorus in 50-100 years.

Did you know that phosphorus is a non-renewable resource? There is only a finite amount of phosphorus on this planet, and once we use up this amount, it can’t be replaced.

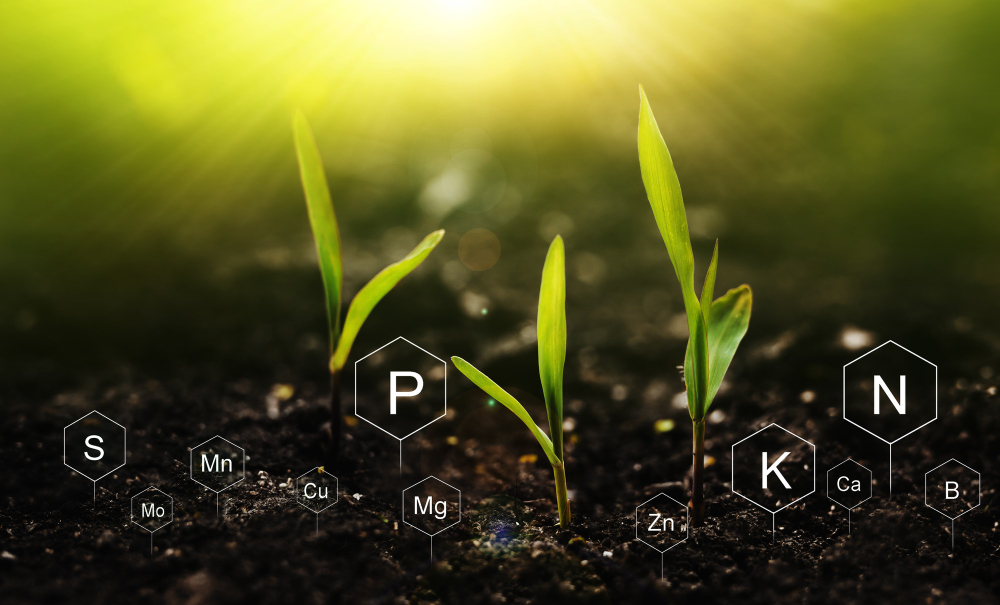

However, phosphorus is a critical nutrient for agriculture and food security. Plants need three primary nutrients: Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Potassium. Sustained food production requires a sustained supply of these key nutrients (along with some others).

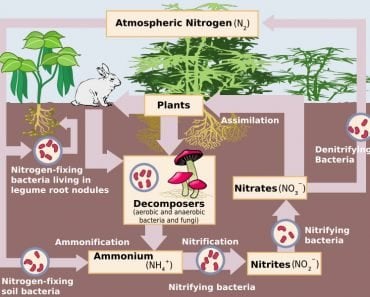

Nitrogen fertilizer is made from atmospheric nitrogen, of which there is an abundant supply. Potassium comes from potash reserves, of which there are finite amounts, but we still have quite a bit of it remaining. It is estimated that at the current rate of use, we have about 600 years of potassium left for our use.

However, we are rapidly using up our limited supplies of phosphorus, as we continue to over-fertilize our fields, and we further lose that phosphorus through our sewage systems.

Securing a long-term supply of phosphorus is key to global food security. What will happen when we use up all the phosphorus on Earth? Are there ways to make our phosphorus supplies last longer?

Recommended Video for you:

Why Do Plants Need Phosphorus And How Do They Get It?

Phosphorus makes up some very important biomolecules. It is part of DNA, RNA, and the molecules that compose your cell membrane. It is also an essential part of respiration and energy transfer in all life, as it is part of the energy currency of the cell: ATP (adenosine triphosphate).

Plants need phosphorus to form new plant cells through cell division, meaning that plants need it to grow. Phosphorus deficiency leads to stunted growth and discolored leaves.

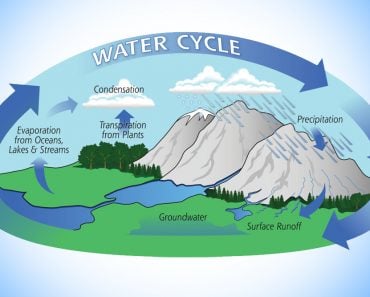

Plants get their phosphorus from the soil. The phosphorus returns back to the soil when the plant dies and decays. This is part of a natural cycle called the phosphorus cycle, which balances the phosphorus levels on Earth.

Now, when we grow crops, it’s a bit different.

Plants use phosphorus from the soil when we grow crops, but every time we harvest crops, the phosphorus that the plant had used and assimilated into itself is effectively removed. We transport those crops to consumers somewhere far away. This phosphorus that is removed from the soil needs to be replenished.

Consumers eat the food and the phosphorus is excreted from their bodies. At that point, the phosphorus enters the urban sewage system along with the excreta.

Traditionally, farmers used manure and human excreta to supplement the naturally available phosphorus in the soil. Fertilizers made from organic waste (human and industrial), animal excreta, slaughter house byproducts and related sources were also used. However, with increasing population, urbanization, and an ever-increasing demand for food, in the mid-19th century, farmers switched to mineral phosphorus fertilizers, which contain a higher concentration of phosphorus.

Globally, we use 148 million tons of phosphorus every year.

Phosphorus Is A Non-Renewable Resource

Phosphorus cannot be synthesized in the lab. It comes from mineral phosphorite or rock phosphate. There is an estimated 68 billion tons of phosphate reserves in the world, but these reserves are not evenly distributed. They are also not equally (and easily) accessible because of geopolitical tensions.

Phosphorus fertilizer is produced after mining phosphorite or rock phosphate, and then treating it with sulphuric acid or phosphoric acid. Crushed rock phosphate itself is also used as fertilizer, but the phosphorus in rock phosphate is very insoluble.

Morocco has the majority (>70%) of the global phosphorite reserves. Other countries with phosphorite reserves include China (5%), Syria (3%), Algeria (3%) and the USA, Russia, South Africa, Jordan and Egypt (3% each).

Although Morocco has the largest reserves, it is not the largest producer of phosphorus, primarily due to political tensions. China is the largest producer of phosphate, and it is estimated that at the current rate, its phosphate reserves will be depleted in 35 years. China has also limited the export of phosphorus to secure its domestic supply. The US has < 30 years’ worth of phosphorus reserves left (estimated in 2009).

Peak Phosphorus: What Is It?

The concept of peak phosphorus was introduced in 2009, and estimates the point at which the production of good quality phosphorus will reach a maximum level. Research estimates this will happen by 2033.

Beyond this point, the quality of phosphorus will decline, and the cost of producing more phosphorus will be greater than the profit. As a result, either the production will decline or the price will significantly increase.

90% of the rock phosphate that is mined is used for food production (human food and animal feed).

It is estimated that with the current rate of phosphate mining and phosphorus use, we will run out of phosphorus in 50-100 years. However, with the increasing global population and changing food habits leading to the need to produce more food, the demand for phosphorus will increase, and we might run out of phosphorus even sooner.

Is There A Solution?

We need phosphorus for food security. This means that we need to find a way to continue maintaining a steady supply of phosphorus in agricultural soil. The solution can be on the supply side or on the demand side.

On the supply side, exploration for more reserves, as well as innovations in how we mine phosphorus, may provide ways to extend this finite resource.

On the other hand, there is significant room for improvement on the demand side.

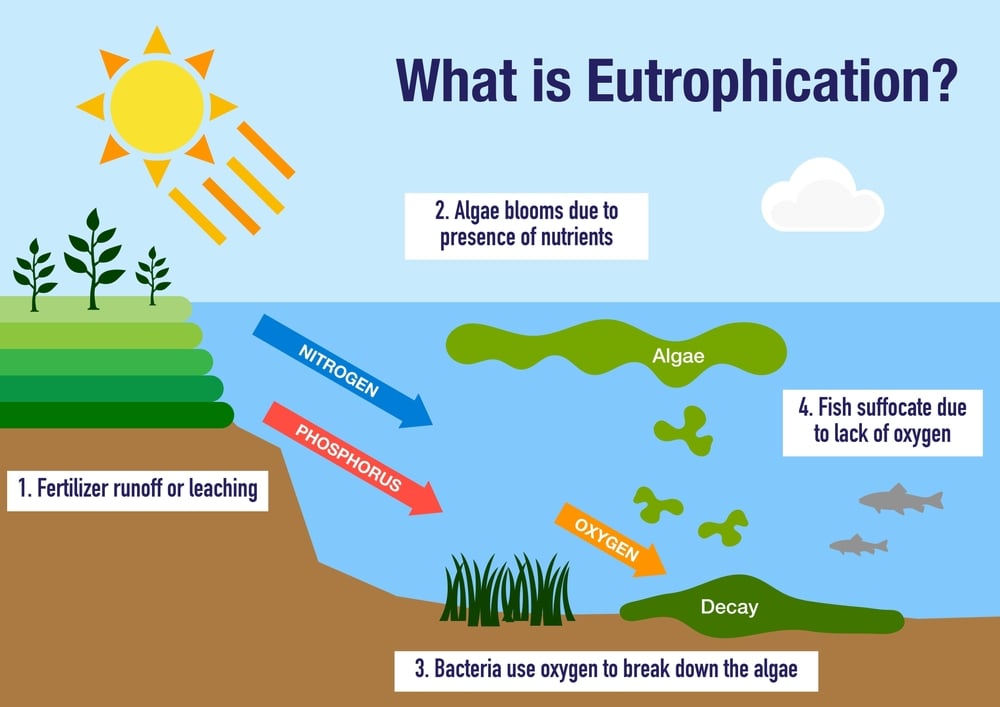

Currently, there is a huge problem with the over-use of fertilizer, which leads to a lot of waste. Only about 20% of the phosphorus we use in agriculture is actually utilized in food production. The rest is wasted through run-off water from fields and leads to the eutrophication of ground water systems.

Understanding the genetics of efficient phosphorus use by plants can lead to the development of crop varieties that use phosphorus more efficiently and will need less phosphorus fertilizer for optimum yield.

In addition, dietary choices also have an implication on how much phosphorus is used. A vegetarian diet uses significantly less phosphorus than a meat-based diet.

Recycling Phosphorus

At the same time, there are significant opportunities to recycle the phosphorus we use. Examples of recycling phosphorus include recovering phosphorus from manure and human excreta.

When farmers use manure, some of the phosphorus used up by the crops destined to become animal feed is returned to the soil. However, the supply for manure in regions with phosphorus-enriched soil is often high, and in areas with phosphorus-deficient soil, it is limited.

Humans excrete almost 100% of the phosphorus consumed in their food and the highest concentration of this phosphorus is in urine. Human excreta often ends up in urban sewage disposal systems and waterways. Currently, only 10% of human excreta is circulated back into the agricultural system.

Other ways to recycle phosphorus including plowing crop residues into the field, as well as composting waste from households, food-processing plants and food retailers.

Conclusion

There is no viable replacement for phosphorus fertilizer today.

Given the importance of phosphorus in ensuring food security, we need a more focused effort to reduce wastage, optimize use, and recycle phosphorus efficiently. Although small-scale trials for recovering phosphorus from waste and excreta exist, it will take many years to do this on a scale that is large enough to support global agricultural production.

References (click to expand)

- (2022, September 15). Approaching peak phosphorus. Nature Plants. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Cordell, D., Drangert, J.-O., & White, S. (2009, May). The story of phosphorus: Global food security and food for thought. Global Environmental Change. Elsevier BV.

- Countries With the Largest Phosphate Reserves.

- Why phosphorus is important.

- Phosphorus Basics | Integrated Crop Management.