Table of Contents (click to expand)

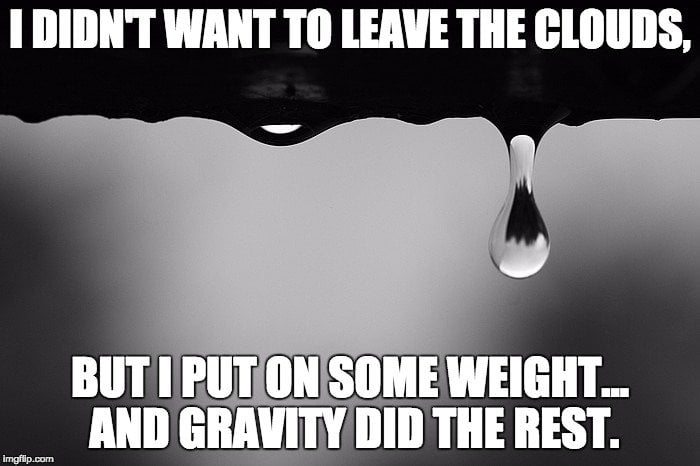

The point at which clouds become heavy enough to rain is when the microdroplets of rain condense and coalesce to the point where their mass becomes affected by gravity.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock for your entire life, there is a very good chance that you’ve been caught in a rainstorm at one point or another in your life. At times, it can seem like rain comes out of nowhere, an unexpected downpour of liquid that drenches you in moments. A few minutes earlier, all of that rain had been contained in a cloud far above your head, so why did it choose that precise moment to tumble down, four blocks from the dry safety of your house?

There must be a tipping point between rain being mysteriously suspended in the clouds, and then deciding to take their earthward plummet… but what it is? At what point is rain simply too heavy to stay in the clouds?

Short answer: When the microdroplets of rain condense and coalesce to the point where their mass becomes affected by gravity. However, rain is a bit more complex than that…

Recommended Video for you:

The Birth Of A Cloud

As most of you know, clouds are formed when water evaporates from the ground. Say that it is a warm day and the bright sun has been beating down on a lake all afternoon. As the liquid water in the lake increases in temperature, it eventually converts to a gaseous state and rises into the atmosphere. However, at this point in the process, the rain is evaporating into microdroplets, which you cannot see. Raindrops are normally visible, so something else is definitely going on…

As billions and trillions of these microscopic water vapor molecules rise into the sky, they form the clouds that we see hanging above us. Those droplets form massive clouds, but those clouds aren’t particularly dense; in fact, the volume of the air in the cloud is 1,000 times greater than the volume of these microscopic droplets.

This water vapor will rise, since warm air rises, but the higher it gets, the colder the surrounding air becomes, which causes this water vapor to return to its liquid form. Cold air cannot hold as much water vapor as warm air, and similarly, under lower air pressure, less water vapor can be held by the air, so a phase change occurs. These new water droplets that form are minuscule, however, 4-5x smaller than the thickness of a piece of paper.

It is also much easier for water to condense on a particle, rather than forming naturally in the air. Therefore, if there is a great deal of dust or other particles in the air, clouds will form much more easily. The variations in the terrain, atmospheric interactions, temperature and wind can all affect the types of clouds that form, but the basic process is the same. However, explaining the different types of clouds is beyond the scope of this article.

The rising warm air beneath these broad areas of water vapor is also strong enough to support the clouds, which is why they appear to “float”, along with all of the rain that they contain. This may seem contrary to everything you’ve learned about gravity, but you need to consider just how small those microdroplets really are; they float in the same way that dust appears to defy the incessant gravitational pull of Earth.

Slowing Down And Getting Fat

As molecules get colder, they also tend to slow down, so instead of bouncing off one another or flowing along with the air, these microdroplets begin to bump into one another and stick. Believe it or not, roughly 1 million microdroplets are required to form an average-sized raindrop. These groups of hundreds or thousands of microdroplets continue combining and growing until they have a mass that can be affected by gravity and cut through the air supporting it from below.

Oddly enough, large droplets struggle to connect with very small microdroplets, due to the powerful movement of air surrounding these interactions. Fortunately, in these cold conditions in the high atmosphere, ice crystals often form, which act as a wonderful catalyst for larger rain droplets. Microdroplets are incredibly attracted to ice crystals, and can increase their weight very rapidly. This may sound like the steps leading up to snow or sleet, but in the process of falling back to Earth, these ice crystals will often return to a liquid state – also known as rain.

Updrafts and general upward atmospheric motions is enough to prevent these gradually growing drops from falling until the right moment. Clouds that eventually deliver a steady sprinkle appear closer to the ground and tend to rise a few centimeters per second; on the other hand, storm fronts can rise 2-3 meters per second, meaning that the transition from warm air to cold air is rapid, hence the downpour of heavy drops that these storm clouds eventually cause.

When you’re walking around in a downpour, it may seem impossible for all of that water to have defied gravity for so long, but due to the massive amount of space/air in the cloud and insignificant mass of the microdroplets for much of their “cloud life”, it takes a group effort to finally fall to the ground.

A World Without Rain

Although many people complain about the particulate matter in the air, as well as the dust in certain regions, if we didn’t have that material present in our atmosphere, it would never rain, making for a very dry planet. At a microscopic scale, water vapor doesn’t have the same freezing point as it does in our tangible, large-scale measurements. In fact, microscopic water vapor can remain in a gaseous form down to -40 degrees (Fahrenheit and Celsius). This threshold is quite cold, and normally only occurs at altitudes higher than clouds form.

Fortunately, due to the particles and dust in our atmosphere, these ice crystals and larger droplets are able to form at higher temperatures (e.g., -10 degrees C). So, next time you see a truck kicking up a lot of dust into the air, don’t be annoyed… he’s helping ensure that we continue receiving life-giving rain from above!