Table of Contents (click to expand)

Human excreta, like the feces of many animals, has nutrients that can nourish the soil. It is rich in nitrogen and phosphorus, two key nutrients for plants. Using human excreta and human excreta-derived materials (HEDM) as manure can solve a number of modern-day problems: reduce our dependence on synthetic fertilizers, improve soil fertility, and help us manage waste. Yet, very few of us would consider food grown on human excreta to be… appetizing.

How would you feel about food grown using your poop?

Surprise, we already do this, in one way or another. Manure is the poop of herbivores and birds, and we even use the bat poop rich in ammonia, called guano, as fertilizer. However, human excreta, associated with prejudice and concerns about safety, either stays where it is or gets flushed into the sewage.

Using human excreta and human excreta-derived materials (HEDM) as manure can solve various modern-day problems by reducing our dependence on synthetic fertilizers, improving soil fertility, and helping us manage waste.

There are also a few examples of human feces being used successfully in agricultural, both historically and in modern times.

Recommended Video for you:

Why Do We Need To Recycle Human Waste?

The global population is projected to reach 8.5 billion by 2030. This rapid increase in population is coupled with rapid urbanization. This has led to challenges in the managing and disposal of human wastes in urban and semi-rural areas. On the other hand, a rapid increase in population also means that our food production needs to increase to ensure that there is enough food to support the population.

The United Nations SDG 2.4 calls for sustainable food production systems that maintain our ecosystems while improving soil and land quality.

They also call for a reduction in waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse.

The reduction of waste generation is possible through recycling human excreta as manure, which would also improve our soil’s organic content.

What’s In The Excreta?

We might call our urine and feces “waste products”, but they still have nutrients that can nourish the soil.

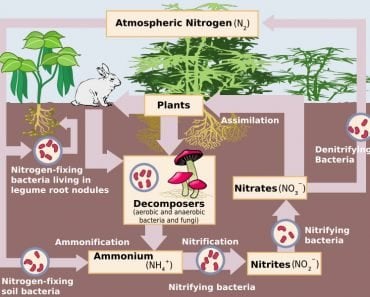

Human urine contains 90% water, 13% carbon, 14-18% nitrogen, 3.7% phosphorus, and 3.7% potassium. Urea accounts for 50% of the organic compounds in urine and 85% of the nitrogen is fixed in urea. The remaining 5% nitrogen is present as total ammonia. Soon after urination, urea is hydrolyzed by bacteria and converted into bicarbonate and carbonate, leaving 90% of the nitrogen present as ammonia.

Human feces contains 75% water by weight and 25% solid material, which includes 50% carbon, 5-7% nitrogen, 3-5.4% phosphorus, and 1-2.5% potassium. Urine and feces also contain micronutrients, such as magnesium and selenium.

All of these nutrients can effectively be recycled to grow crops. It has been estimated that 520 kg of human excreta can produce 7.5 kg of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and micronutrients that can produce 250 kg of grain—enough food for one person per year.

However, human excreta also contains pathogens, heavy metals, pharmaceutical drugs, and synthetic hormones, which means we must treat human waste before putting it to use in the fields.

This Is Not A New Idea

Humans have been using excreta for agricultural purposes since at least the early 9th century. Countries like China and Japan have used human waste as fertilizer since the 16th century.

In the 18th century, human waste was highly valued for its use as manure in farms in Japan, where there was limited fertile land for agriculture. Therefore, human excreta from densely populated cities was transported to farmlands. There are reports that farmers who couldn’t afford to buy poop would even steal it, a crime that was punishable by law. This demand also kept the cities clean, as all the waste was collected and used.

European farmers started using human waste fertilizer in the 19th century, but later switched to synthetic fertilizers. Some small farmers in China, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America continue to use human excreta as manure.

The ‘Ick’ Factor

In spite of data on the benefits of using human excreta as manure, consumers and farmers may be resistant to the idea due to socio-cultural taboos. Farmers do not want to use fresh excreta as manure because, “[…] fresh excreta are associated with bad smell, visual repulsiveness and various kinds of potential diseases.” There is also the fear of health risks associated with handling human waste.

A survey of 400 farmers in Ghana concluded that the majority (87%) considered human excreta as a health risk that should not be handled manually or otherwise. However, they agreed that human excreta are good for crops. This survey concluded that women, in general, have a more negative perception about human excreta than men. They also noted that vegetable/fruit crop growers are less likely to adopt human excreta manure than grain crop farmers.

Another concern is whether consumers will be willing to eat produce that is grown with human excreta. In the survey conducted in Ghana, the participants did not ‘think’ that human excreta would alter the taste or quality of the produce and they said that they would eat it.

Even when farmers are willing to use HDEM, consumer and regulatory barriers prevent them from adopting it. Cultural and religious barriers may also make human excreta a taboo that should not be handled, even when communities realize the potential of its use.

Regulations around the use of human excreta as manure are unclear, which poses a challenge to its use in commercial agriculture. This is especially true for farmers who grow produce for the export market, as they must comply with regulations of their target markets and a sometimes unknown third party.

For example, one international quality assurance certifier, Global GAP, does not allow the use of treated human sewage in farms. Therefore, all farmers certified by Global GAP are unwilling to adopt human excreta manure.

More Data Is Needed

More data on the safety and efficacy of using human excreta as manure may help with wider acceptance, both among consumers and regulatory bodies.

Researchers in Germany grew cabbage in soil supplemented with three types of HDEM, two from human urine and one from human feces, and compared the yield with a commercial organic fertilizer. The yield from urine-based fertilizers were comparable or higher than commercial fertilizer, while yield from the feces-fertilized crop was 20-30% lower. However, the feces-based fertilizer improved soil carbon content, which is a long-term effect.

More importantly, they assessed the safety of these fertilizers by testing the human excreta for chemicals, such as insect repellants, rubber additives, flame retardants, painkillers and hormones. Almost 93% of them were not detected and the remaining 7% were detected in very low concentrations. For example, they detected carbamazepine, a drug used for treating neurological disorders, in such low concentrations that the researchers calculated a buyer would need to consume ‘half a million heads of cabbage to take the equivalent of one carbamazepine pill’.

Conclusion

Farmers are aware of the benefits of using human excreta in improving soil nutrient value and reducing their cost of operations. However, they are sometimes hesitant to use it because of social taboos and concerns about consumer acceptance.

Processing human waste through treatment technologies, pelletizing, packaging and certification to make the products safe can be a way to increase adoption. The use of treated human excreta also takes care of the perceived health risk. Local certification and assurance schemes that adequately test the safety of human excreta manure and then permit its use may encourage even wider adoption, which would certainly benefit our hungry and ever-growing population.

References (click to expand)

- A History of Human Waste as Fertilizer.

- Gwara, S., Wale, E., Odindo, A., & Buckley, C. (2021, February 13). Attitudes and Perceptions on the Agricultural Use of Human Excreta and Human Excreta Derived Materials: A Scoping Review. Agriculture. MDPI AG.

- Fred, N., Kwasi, O.-Y., Kofi, P., Flemming, K., & Robert, C. A. (2014, October 1). Farmers perception on excreta reuse for peri-urban agriculture in southern Ghana. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics. Academic Journals.

- Harder, R., Wielemaker, R., Larsen, T. A., Zeeman, G., & Öberg, G. (2019, January 29). Recycling nutrients contained in human excreta to agriculture: Pathways, processes, and products. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology. Informa UK Limited.

- Sugihara, R. (2020). Reuse of Human Excreta in Developing Countries: Agricultural Fertilization Optimization. Consilience, No 22 (2020): Issue Twenty Two: 2020.

- Moya, B., Parker, A., & Sakrabani, R. (2019, May). Challenges to the use of fertilisers derived from human excreta: The case of vegetable exports from Kenya to Europe and influence of certification systems. Food Policy. Elsevier BV.