Table of Contents (click to expand)

Butterflies do store memories from their days as caterpillars. The brain structures called mushroom bodies, associated with learning and taste, are retained during metamorphosis. This allows the butterfly to remember dangerous or inedible foods learnt during its caterpillar days. This is called fear conditioning.

As we grow older, we create new memories but never forget our childhood. Most are fortunate to have home videos, photographs or family and friends to help refresh those good ol’ memories. Turns out that even without the help of modern technology and family, butterflies can also remember their childhood caterpillar selves!

Recommended Video for you:

What Is Metamorphosis?

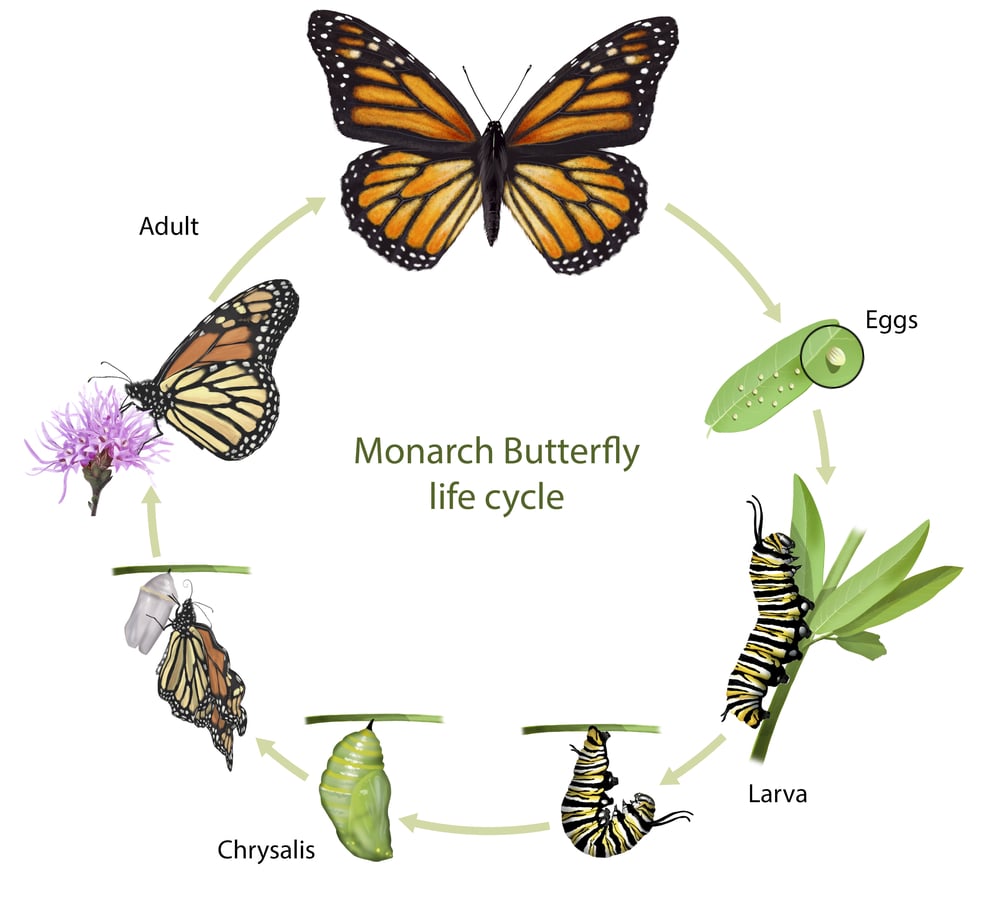

For a caterpillar to mature into a butterfly, it must metamorphose.

Metamorphosis is a bewitching natural phenomenon. In biology, it refers to the impressive transformation of shape, structure, or both after proceeding from the juvenile larval stage to the adult stage in an individual’s life cycle.

Some examples of metamorphosis are more subtle, as in the case of a starfish. They undergo a change in symmetry, shifting from the bilateral symmetry of larvae to the radial symmetry of adults. Several other changes distinguish the larval and adult stages of the starfish, but overall, they continue being the aquatic beings that they were upon being born.

Some animals, on the other hand, go through a dramatic change that makes them almost unidentifiable from their larval form. They are so different, in fact, that they are known by different names in these two stages. The aquatic tadpole that changes into the semi-aquatic frog are the same animal, but merely in different stages of life.

However, the most noteworthy transformation in nature has to be growing a pair of wings!

Growing wings is exactly what a caterpillar does when it metamorphoses into a butterfly. Imagine being as slow as a snail and then growing up to be able to fly like the birds (well, not exactly). This transformation is one of the most remarkable feats of nature and has mesmerized poets and scientists alike.

It’s Not Magic, It’s Science!

Right from birth, it is the destiny of a caterpillar to turn into a butterfly and its organs know that. A collection of cells called imaginal discs present in even a tiny larva are already configured to develop into adult structures like wings, antennae, genitalia and legs. However, a constant flood of juvenile hormone produced by the caterpillar prevents these cells from developing prematurely.

The job of a caterpillar is only to feed. While it feeds, doing so in order to reach a certain size, its muscles, gut and other internal organs develop. Even so, the imaginal discs stay subdued during this time and remain inactive.

When the caterpillar reaches a crucial size (which varies from species to species), the concentration of the juvenile hormone in its body is very low. A burst of the molting hormone, ecdysone, at this stage allows the caterpillar to exit the larval stage. The caterpillar molts and sheds its skin to reveal a hard shell, known as the chrysalis or cocoon. The imaginal discs catch up on the development process inside the chrysalis and grow into the characteristic features of butterflies.

When there is no juvenile hormone present in the body, ecdysone is released once more, triggering the emergence of a beautiful butterfly from the cocoon. The butterfly flies off to mate and lay eggs, thus continuing the life cycle.

But what happens inside the cocoon? Does the caterpillar turn into some sort of nutrient soup before undergoing renovation? Do its brain tissues survive this process?

Inside The Cocoon

For a long time, scientists thought that caterpillars were reduced to pudgy mush inside the chrysalis and then rebuilt into butterflies. It was believed that enzymes that break down tissues, like caspases, were released, dissolving the caterpillar’s tissues, especially cells of the muscle and gut that weren’t needed in a butterfly.

The size and structure of the gut is dramatically reduced, as butterflies only need to survive until the mating stage. On the other hand, new muscle cells are generated to support the shift from crawling to flying.

However, contrary to previous belief, rather than being reconstructed entirely, the butterfly is now seen as a remodeled caterpillar. CT imaging showed that some of the key structures remain relatively unchanged, barring a few adjustments to make the new body more efficient.

For example, the tracheal tubes through which an insect breathes are untouched, since they are necessary for respiration. These breathing tubes grow in size to fuel the body with more oxygen, as flying is more energetically costly than walking.

However, the situation gets more complicated when it comes to the brain. The brain is composed of many different parts, making it difficult to confidently pinpoint which parts undergo modifications in the cocoon.

A study provided evidence of memory retention by literally shocking some caterpillars. Manduca sexta, commonly known as hookworm caterpillars, were trained to dislike and avoid the scent of ethyl alcohol by subjecting them to mild electrical shocks whenever they smelt it.

The researchers then placed the caterpillars at the bottom of a Y-shaped tube that had ethyl alcohol fumes in one arm and no scent in the other. 78% of the conditioned larvae crawled away from the scented arm and into the one with fresh air.

At first, the conditioning was lost after the caterpillars transformed into butterflies, but astonishingly, when the training was provided at later stages in the larval cycle, this aversion to ethyl acetate was retained even after the caterpillar had metamorphosized. 77% of such butterflies continued to go down the arm with fresh air when re-introduced to the Y-tube setup after their metamorphosis.

This study proved that the neural tissue responsible for taste, smell, memory and learning remain intact during metamorphosis. Anatomical evidence also supports this finding. Corpora pedunculata or mushroom bodies are paired structures found in an insect’s brain. At the larval stage, mushroom bodies are responsible for ‘tasting’ with the antennae, along with affecting learning and memory. In the adult stage, they are not only responsible for ‘tasting’ and learning, but also for ‘smelling’.

Hence, they probably formed an association between the painful shock stimuli and the ‘taste’ of ethyl acetate. As the mushroom bodies are very critical for the organism’s survival, they remain largely unmodified, while the rest of the brain may undergo modifications to keep up with the new body. The adult butterfly therefore retains knowledge of the association between the shock stimuli and ethyl acetate.

It is important to note that the memory of insects like caterpillars and butterflies is very different from human memory. Insect memory is limited to matters of survival, such as what’s good to eat and what’s not, and what should I definitely fly away from versus fly towards.

In summary, unlike humans, butterflies cannot remember personal experiences (if any) from their time as a caterpillar. Their memory is strictly biological, allowing them to recall things that endanger their well-being—like an electric shock!

References (click to expand)

- Do Butterflies Remember Being Caterpillars? | SiOWfa16. The Pennsylvania State University

- What Happens Inside a Cocoon or Chrysalis?. askentomologists.com

- How does a caterpillar turn into a butterfly? | Discover Wildlife. BBC Wildlife

- Butterfly Brain - Ask A Biologist | - Arizona State University. Ask A Biologist

- Blackiston, D. J., Silva Casey, E., & Weiss, M. R. (2008, March 5). Retention of Memory through Metamorphosis: Can a Moth Remember What It Learned As a Caterpillar?. (S. Healy, Ed.), PLoS ONE. Public Library of Science (PLoS).

- Lowe, T., Garwood, R. J., Simonsen, T. J., Bradley, R. S., & Withers, P. J. (2013, July 6). Metamorphosis revealed: time-lapse three-dimensional imaging inside a living chrysalis. Journal of The Royal Society Interface. The Royal Society.