Table of Contents (click to expand)

Plants do feel stress from the environment and other activities, but their response to such stimuli is very different from our idea of stress, since plants lack a nervous system and traditional brain.

Imagine that you are walking home after a long day at work, during which your boss yelled at you multiple times, you started showing the early signs of a cold, and you missed a deadline for an important client. As you step off the curb to cross the street, the screeching horn of an oncoming car shocks you into action and you leap back in time to avoid being struck. Your heart is racing, your breathing gets shallow and you immediately break out into a sweat. Suffice to say, you are stressed out in every possible way—physically, emotionally and psychologically.

However, while human beings and animals experience and demonstrate stress in ways that we largely understand, many people wonder if the same thing is true of plants. Basically, what is the equivalent of a plant feeling nervous before a test? Or a plant feeling a surge of energy after finding itself in a dangerous situation? Can plants feel stress and pain, or is that something only sentient life can experience?

Recommended Video for you:

Plants In Nature

When a human being or other mobile sentient creature encounters a stressful experience, such as narrowly avoiding an accident or attempting to elude a predator, they are often benefitted by their “flight or fight” reactions. They must choose to either fight and defend themselves, or run away and seek shelter from the threat. Plants, however, are quite literally rooted to the ground, and are therefore unable to escape from or remove themselves from dangerous or uncomfortable situations.

When we think about predator and prey in the wild, we rarely think of plants as fitting into the same paradigm, but they do! Remember that every herbivore and omnivore on the planet (organisms that eat plants) are predators from the perspective of plants! Furthermore, aside from sentient predators, plants must also be able to defend against natural threats, such as rainfall, excess heat, disease, freezing temperatures and drought. Plants that are unable to withstand or avoid such stressors will be unable to grow, produce viable seeds and reproduce. Clearly, given the nearly 400,000 species of plants that have been identified around the globe thus far, the flora of Earth has developed its own ways to respond to stress.

Stress Response In Plants

When a plant undergoes a difficult period, stressed by weather, predators or disease, there are not many options—adapt or perish. The less preferred option is death, but it’s not always a terrible option. Many plants are short-lived because they lack any adaptations to survive challenging times, but their reproduction is often taken care of by then, so succumbing to death isn’t a failure in the grand scheme of their species.

In terms of plants that are able to survive and “weather the storm”, per se, they acclimate by developing ways to continue producing seeds, despite the challenges to their homeostasis. Plants that can deal with fluctuations in temperature and water levels without dying are often referred to as hardy plants, versus those that are susceptible to small fluctuations in their surroundings. Hardy plants gradually evolved certain characteristics as their entire population acclimated to new conditions. Some of these characteristics allow them to overcome environmental challenges, such as heat-shock proteins, or the ability to change their leaf size depending on growing conditions. These adaptations are the result of natural selection, and provide long-term protection and resilience against regular or seasonal stress.

Equivalent Of A Flight-or-fight Response

Finally, there is the acute stress response of plants, which is most similar to our own fight-or-flight response. In the event of an immediate threat, such as a predator eating its leaves or a fungi beginning to grow on its roots, a plant will have a hormonal response. In the case of humans, our hormone regulation is controlled by the endocrine system, while neurotransmitters are managed by the nervous system. The brain directs these systems to release critical compounds at precisely the right time to maintain health and homeostasis. Plants, however, do not have a nervous system, endocrine system or brain; instead, every single plant cell is able to produce its own hormones!

Plant hormones control every single step in the growth, development, reproduction, and defense of the plant, which includes stress response. The simple chemicals used by plants are transported where they’re needed through four methods—cytoplasmic streaming, slow diffusion, via xylem, or via phloem. Most of the hormones are only used during certain stages of a plant’s life cycle, while others, such as stress response hormones, can be produced and implemented at any time.

Abscisic Acid

Abscisic acid is a particularly popular plant growth regulator that is generated by the chloroplasts when a plant is experiencing stress. It will inhibit bud growth and may impact bud dormancy, when the conditions aren’t right for growth. In the case of water stress, or drought, this same hormone can close the stomata, preventing water loss through evaporation.

Salicyclic Acid

Salicylic acid is a hormone that functions as an alarm system within plants. If a plant is being attacked by some sort of pathogen, it will be released from the cells to aid in the defense. Furthermore, it can be aromatically released as a warning to neighboring plants of the pathogen attack, so that they can better prepare themselves. This type of “communication” between plants is often mistaken for intelligence or cognition, but is instead the result of chemical pathways automatic triggers.

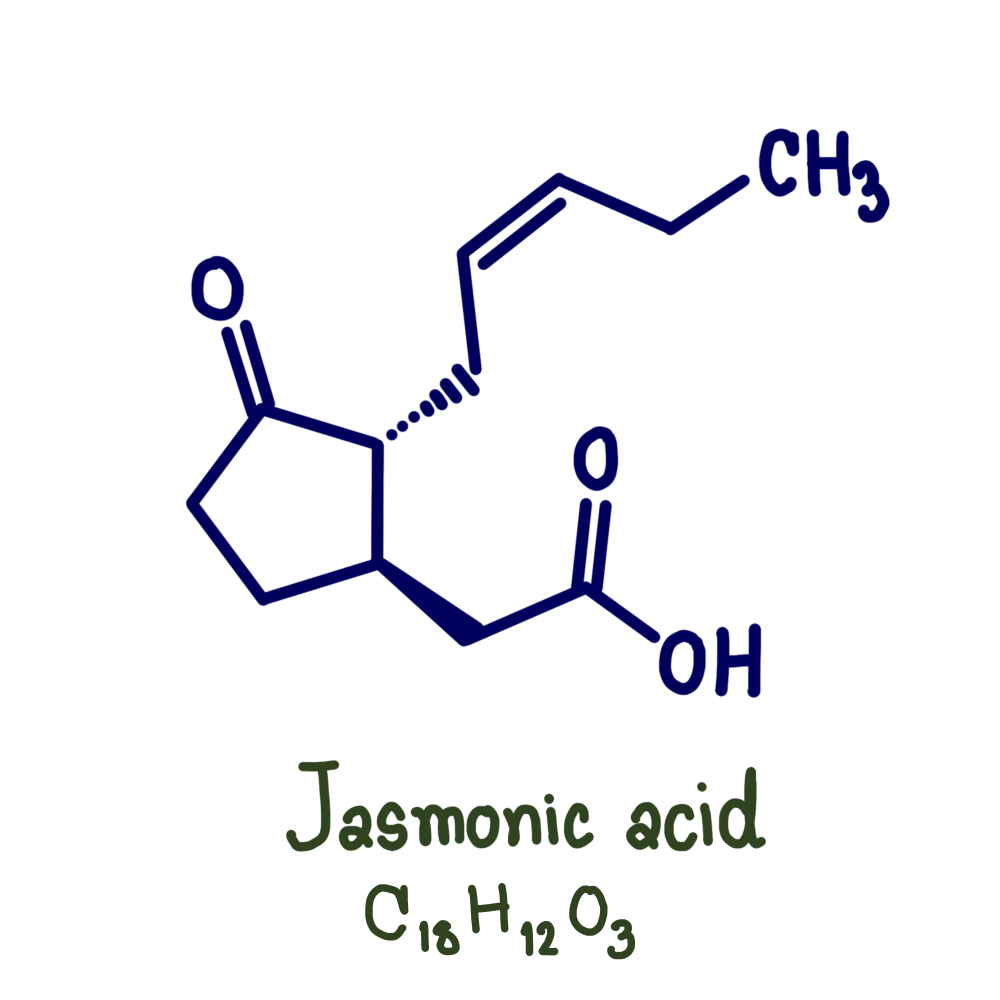

Jasmonic Acid

Jasmonates, particularly jasmonic acid, is a class of hormones that has a number of functions. It works as both a defensive substance and an airborne pathogen warning system to other leaves of the plant and nearby plants. In terms of its defensive characteristics, the powerful aromatics are unpleasant to predators, both above- and below-ground herbivores. Nitric oxide is yet another simple compound that is deeply involved in the signaling of stress response in plants.

In conjunction with dozens of other plant hormones that are produced, used and catabolized throughout every stage of a plant’s life cycle, these defensive hormones play a key role in protecting individual plants from a variety of threats.

A Final Word

Just because plants don’t have a nervous system like humans doesn’t mean they aren’t able to recognize and respond to danger. While the debate over whether plants can “feel pain” often veers into philosophy, the question of whether plants feel stress is not in question. Stress is a part of life, as environmental conditions change and organisms are forced to adapt or respond.

Stress in plants is not necessarily a bad thing, but we often associated and anthropomorphize it as a “painful” experience. In some cases, stress allows a plant to learn more about its environment so it can be better prepared for the future. In other cases, stress drives the process of natural selection and greater adaptations so a species will be able to persist. This isn’t all that different from the human experience with difficult situations; for some people, there is no better motivator to overcome a challenge than a solid dose of stress!

References (click to expand)

- Okada, K., Abe, H., & Arimura, G.-. ichiro . (2014, November 4). Jasmonates Induce Both Defense Responses and Communication in Monocotyledonous and Dicotyledonous Plants. Plant and Cell Physiology. Oxford University Press (OUP).

- Wasternack, C. (2007, May 18). Jasmonates: An Update on Biosynthesis, Signal Transduction and Action in Plant Stress Response, Growth and Development. Annals of Botany. Oxford University Press (OUP).

- Loake, G., & Grant, M. (2007, October). Salicylic acid in plant defence—the players and protagonists. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. Elsevier BV.

- Arasimowicz, M., & Floryszak-Wieczorek, J. (2007, May). Nitric oxide as a bioactive signalling molecule in plant stress responses. Plant Science. Elsevier BV.

- HIRON, R. W. P., & WRIGHT, S. T. C. (1973). The Role of Endogenous Abscisic Acid in the Response of Plants to Stress. Journal of Experimental Botany. Oxford University Press (OUP).