Table of Contents (click to expand)

The short answer is no. Not all evolutionary change needs to be a response to external selection pressures. They can also just be random or neutral in nature. Very often, evolution is branched, so there is no one straight line.

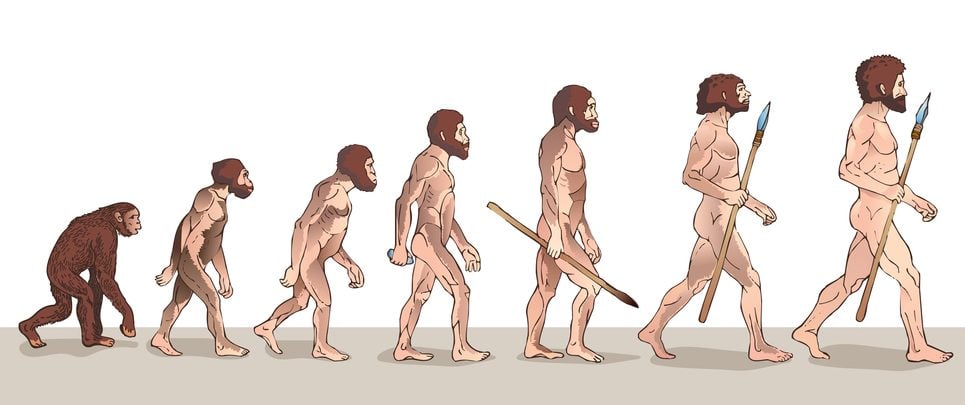

When we think of evolution, many of us think of this famous picture:

However, this picture, which depicts the evolution of man, may actually pose a danger to our general understanding of how evolution plays out on the planet. One might interpret the picture as: Evolution is a unidirectional, progressive process for the betterment of species. This, in fact could not be farther from the truth.

So, what is evolution exactly?

Recommended Video for you:

What Is Evolution?

Evolution today is referred to or used in the context of the origins of early life or with respect to tracing the ancestry of a group of animals.

Interestingly enough, when Charles Darwin, the father of evolution, first described the mechanisms of evolution in his book, “On The Origin Of Species,” he never used the word “evolution”. Instead, he described it as descent with modification.

This is also the most popular answer to the question. In fact, it’s what most people learn or think of when they think of evolution. However, it does lead to some misunderstandings. One is that evolution refers to improvement or growth. Second, it implies that descendants are more advanced than their primitive forms. This casual use of the word “evolution” poses a dangerous challenge in scientific circles, as it promotes the theory of orthogenesis.

What Is Orthogenesis?

Orthogenesis is the theory of progressive or directional evolution. It was coined by Wilhelm Haacke, and heavily influences mass audiences in terms of how we view and understand the process of evolution.

Orthogenesis posits that organisms have a driving force or an innate and intrinsic tendency to evolve toward a “goal”. In general, we can liken this goal to the complexity of life.

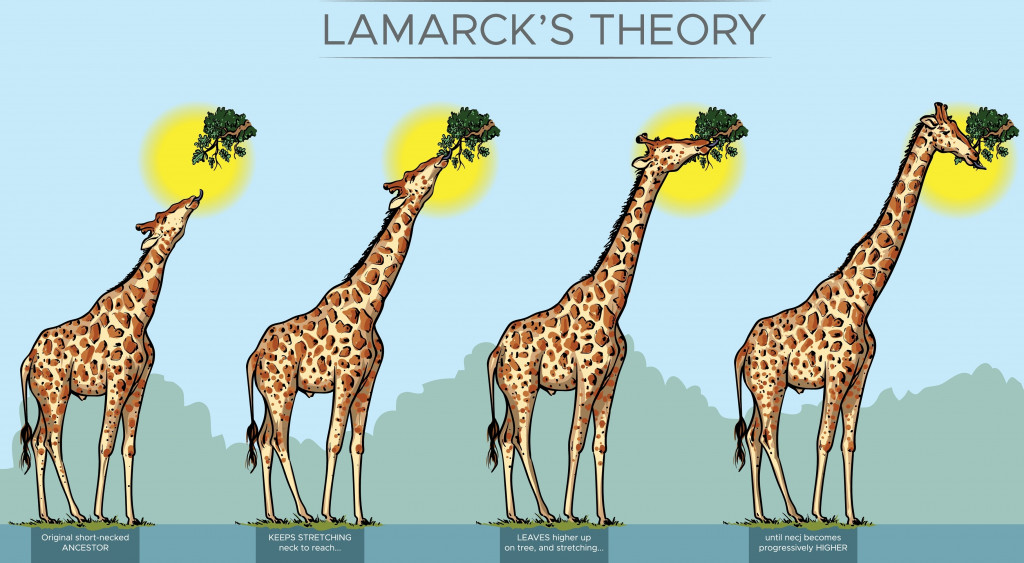

Earlier renditions of an orthogenetic-like theory had prominent scientists who championed it, for example, Jean Baptiste Lamarck.

Lamarck even came up with his two-factor theory to further opine on the validity of orthogenesis. He posited two conditions: the first was that a “complexifying force” drives animals to evolve towards a higher body plan; and the second was that adaptive forces also cause animals to change their body plans based on their circumstances (the second factor is more commonly referred to as the theory of use and disuse).

Yet, it wasn’t until Wilhelm Haacke, in 1893, that the word “orthogenesis” was first used in reference to directed or progressive evolution. That said, Haacke wasn’t a champion of orthogenesis. In fact, beyond his coining of the term, he didn’t really go on to contribute much to the idea. It was another scientist, Theodor Eimer, who popularized and reinvigorated the theory of orthogenesis. He did this by giving it meaning; literally, he was the first man to give it a genuine definition.

According to Eimer, Orthogenesis was a law that governed evolutionary development. He believed that evolutionary development was directed towards something and that the directionality was always noticeable.

Lamarck famously used the example of the lengthening of a giraffe’s neck to promote his theory of use and disuse. (Photo Credit : EreborMountain/Shutterstock)

Think of it like this, if animal A is inferior to animal B, according to the orthogenetic theory, this means that Animal A evolves into Animal B.

Towards the mid-twentieth century, scientists such as Ernst Mayr and George Gaylord Simpson worked to change the orthogenetic notion of evolution. Mayr went so far as to call orthogenesis, “[…] some supernatural force […]” and hoped to disavow its use in scientific journals.

How Much Does Orthogenetic Theory Get Wrong?

Quite a bit.

The orthogenetic theory stands by a number of outdated principles.

One of these principles refers to the unidirectionality of evolution. Supporters of orthogenesis often claim that the nature of evolution is inherently beneficial or progressive in one direction.

This isn’t always true for two reasons. Evolution can be progressive in nature (or responsive to a need or purpose in the surrounding environment), but this doesn’t always mean that evolutionary changes always favor progression.

Basically, not all evolutionary change needs to be a response to external selection pressures. They can also just be random or neutral in nature.

Take, for example, vestigial organs. If we were to believe orthogenetic theory (more specifically, Lamarck’s theory of use and disuse), vestigial organs would simply perish. Yet human bodies still have appendixes, wisdom teeth, and redundant pinna muscles.

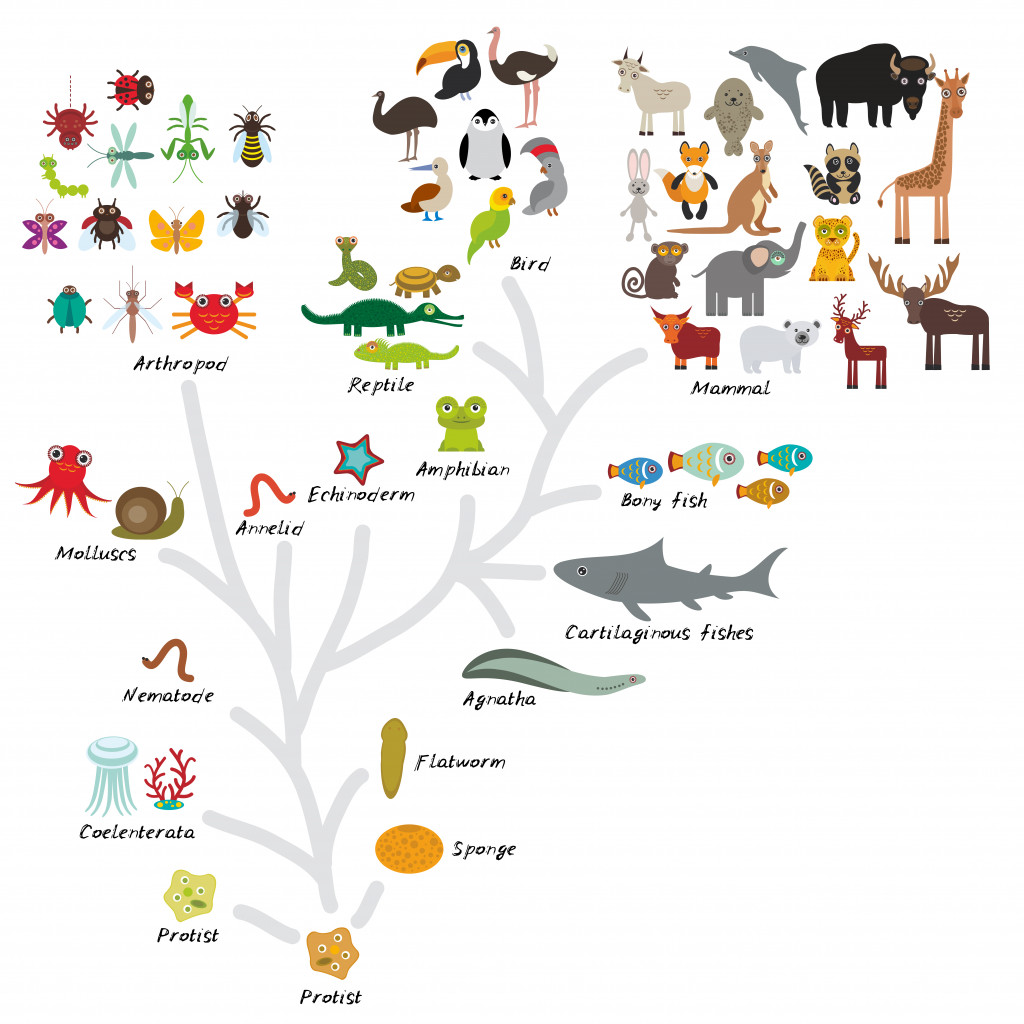

Secondly, even if all evolution were to be progressive, that progression isn’t unidirectional. Rather, it is heavily branched!

From a common ancestor, descendants can diverge in different directions. Say animal A and animal B both evolved from animal C. Animal A specialized to feed on grain, while animal B specialized to feed on smaller prey. We cannot extrapolate that animal A is evolutionarily inferior to animal B or vice-versa. They both simply evolved in different directions.

A good example of this is the evolution of primates. As much as we pretend otherwise, humans are animals. More, specifically, we are primates. At some point in the past, we branched off in a different direction of evolution from our primate brothers and sisters, like chimpanzees or bonobos. This doesn’t mean that humans are more evolved than chimps. Rather, what we can take away from this is that both humans, chimps, and bonobos continued to evolve, but in different directions.

Additionally, orthogenesis seems to denote that due to the unidirectionally of evolution, ancestors are biologically less complex or “less evolved” than their newer descendants.

A Final Word

When Darwin put down his first definition of evolution as descent with modification, he might have chosen his words a bit more carefully. The current consensus around evolution can be simply framed as change over time.

Mechanisms such as mutation, selection, genetic drift, and gene flow mediate the evolution of species.

However, an important distinction must be made with reference to evolution. Evolution doesn’t produce progressively better animals.

In fact, it isn’t even purely directional. Natural selection, an evolutionary mechanism, is directional, but other mechanisms such as mutations and gene flow are random in nature.

The evolution of species does not progress in straight lines. The easiest way to understand evolution is based on the diversification of species, and the remarkable branching ability of our tree of life.