Table of Contents (click to expand)

The climate has had a huge impact on how we’ve evolved as a species. Changing climatic conditions during the Ice Age made us evolve innovation as a culture, which helped us survive. Culture, in turn, has influenced our evolution.

Imagine that you live somewhere close to the equator, say Brazil or Indonesia. Chances are good that you’re pretty well equipped to deal with hot and humid temperatures. Suddenly, imagine being dropped off at a random location in Greenland. You would struggle quite a bit with the suddenly cold and dry environment around you, but eventually, you might find that you can get used to your new surroundings.

Recommended Video for you:

How Would You Adjust?

When we imagine the above scenario happening to us, we think of fairly innocuous changes or simply new learned behavior. We think about simple things, such as switching up our diets or what we wear. Obviously, tropical fruits and grains, like corn or rice, which thrive near the equator, won’t grow in Greenland.

You’ll adapt your diet to whatever is available in Greenland: meat from wild game and fish. Of course, you’d also probably seek out indigenous people from the area and ask them for advice.

However, beyond these lifestyle changes, we’re also affected by such changes in climate on a genetic level.

Why Does This Matter?

This might seem like a statement of painfully obvious facts, but we’re zeroing in on something that is generally overlooked when we talk about or learn about human evolution. This thing, specifically, is culture.

What Is Culture?

Culture can be understood as a way of doing things. It is a tendency that develops over time and space in a given population or across multiple populations. For example, humans living in colder areas wear thicker clothes. That’s a tendency particular to them.

When we think of human evolution, we’re hardwired to think of genetic changes, heritability and mutations. Very rarely do we associate it with culture, yet culture is what defines the evolutionary success of human beings. Human beings are incredibly adept at adjusting to new environments.

To understand how culture impacts evolution, let’s consider the umbrella.

Using An Umbrella: An Evolutionary Cheat Code

When we think of climate change shaping evolution, we expect drastic changes, but most of the time, it’s the subtle changes that make all the differences.

Imagine two genetically distinct groups of animals living in a part of the world where every day is a rainy day.

Let’s call these groups of animals group A and group B.

A few animals in group A are resilient, and despite not having any method to cope with the rain, they still manage to survive long enough to reproduce. The offspring of group A again either perish or are innately able to cope with the rain.

This cycle of natural selection goes on for many generations that span a few decades, or even a century. Eventually, group A consists of a group of animals that can survive the rains. Natural selection, combined with heritability and mutations, has produced a group of animals that can “deal with” rainy conditions.

Meanwhile, group B is made of animals ill-suited for the rain. However, one animal in group B noticed that it could shield itself from the rain by holding a large leaf over its head. The other animals in the group noticed and followed suit, thus learning the novel leaf-holding behavior. They even noticed that they could stitch the leaves together to make larger make-shift shelters.

So, while group A became better suited for the rainy habitat, that acclimatization took a lot of time.

Group B, however, became better suited to their new rainy habitat by innovating novel behaviors and enabling group-wide communications. Sure, natural selection may have identified smarter and more innovative individuals over the years, but rather than just wait for their bodies to evolve, group B enacted a novel culture.

In essence, culture is a non-genetic change or a behavioral change. It can be something as simple as using an umbrella, or learning how to make one from leaves when it rains.

Does Culture Really Matter That Much In Evolution?

This may sound strange, but we are living in an Ice Age. More specifically, we live in the interglacial period of the current Ice Age.

Ice ages aren’t discrete moments in time. They last for really, really, really long periods of time. What we refer to as the “last” ice age was actually the glacial period of the Ice Age. During glacial periods of an ice age, the climate is very, very cold, but in the interglacial periods, the climate changes. From the warming of the oceans to the thawing of permafrost, the world isn’t just cold anymore. Everything after the glacial period of the ice age or the Pleistocene was immediately followed by the Holocene, the age of “now”.

The Age Of Man

Towards the end of the last glacial period of the ice age, approximately around 12,000 years ago, Homo sapiens were the last humans left standing. Literally. Our closest cousins, the Neanderthals, went extinct around the same time.

It wasn’t that Homo sapiens suddenly inherited new genes that enabled our continued success. In fact, Homo sapiens had to be inventive long before the interglacial period. As a species, we were scrawny and small. Our adaptive successes began during the glacial period of the ice age itself.

In an interview for the Smithsonian Sparks series, paleoanthropologist Briana Pobiner had the following to say about ancient Homo sapiens:

“Neanderthals had physical features that helped them survive cold climates, like large noses to humidify and warm dry, cold air and short, stout bodies to conserve heat, but early Homo sapiens had technology that Neanderthals didn’t, including sewing needles to make clothing, important during the colder periods of the Ice Ages. Homo sapiens also had innovative tools like bows and arrows and seemed to have a more diverse diet than Neanderthals.”

In fact, in the same piece, Pobiner alluded to the fact that as early as when Neanderthals still existed, Homo sapiens had set up long-distance trade networks to combat unfavorable climates and conditions. Essentially, instead of braving the cold like the neanderthals, Homo sapiens were buffering their odds by possibly securing foods from alternative sources in unfavorable times. They did things in a new way. Essentially, this is innovation… it’s a culture!

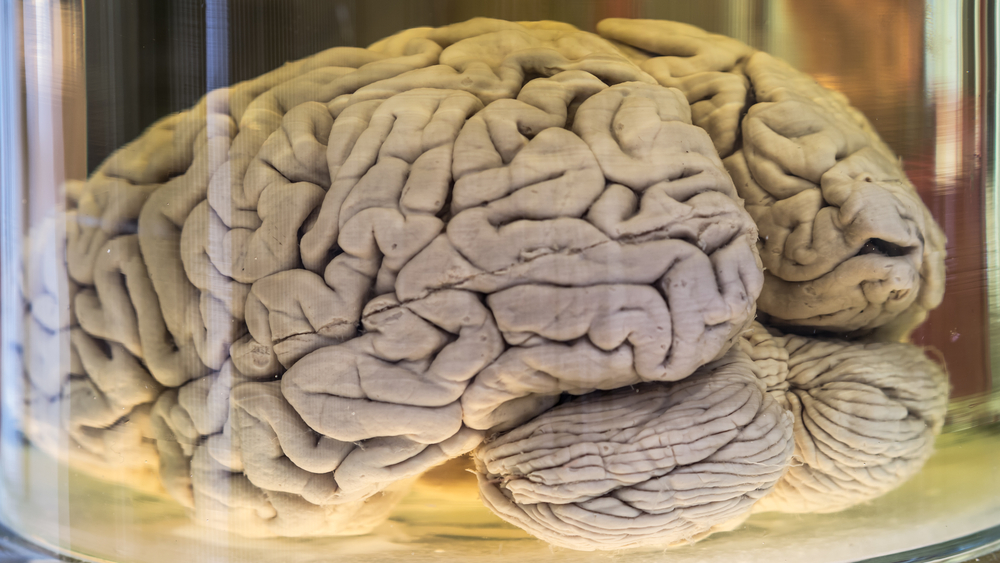

This culture of innovation can be boiled down to good use of pre-existing genetic advantages. At this point, Homo sapiens were already pretty good at talking to one another by virtue of their big brains. A wide range of factors had contributed to an increased processing capacity and size of sapiens brains, but that is the subject of another article!

Although Homo sapiens were still pretty physically scrawny, as compared to other hominin species, their brains gave them an edge. Unlike other hominins, or even animal species at that time, Homo sapiens were able to talk to and explain things to each other. They could work well with each other for collective tasks.

As the world climate switched, from the cold and dry weather of the glacial period to the new conditions of the interglacial period, Homo sapiens collected and documented immense stores of information with respect to their new climate. They learned as much as they could about the new seasonal patterns, as well as edible plants, and even recorded times of animal migration.

By collecting and documenting information about the new climate, ancient humans better understood how to navigate their new environment, find sources of food and water, and avoid potential danger. They learned to do new things and learned about new things, and could then pass down that novel information to new generations. This eventually contributed to the long-term survival and success of the group.

In an article published by the Discover Magazine, paleoanthropologist Rick Potts, who heads the Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Program, opined that even Homo sapiens‘ penchant for migration and dispersal could be used to explain how we made it out of the glacial period. We didn’t sit down and hunker through the cold; we moved to more habitable areas.

According to Potts, early humans didn’t have a map. “They were just going over to the next valley and hillside to see what was there, and some of them went quite a distance.”

Conclusion

Neanderthals are also members of the Homo genus and are actually quite a bit closer to us on the phylogenetic tree than we realize. In fact, for a period of time, approximately 50,000 years ago, neanderthals and sapiens lived in the same geographic locations, primarily Europe, both during and after the Ice Age.

Although bigger, larger, and stronger than us, our hunky cousins didn’t make it past the end of the Ice Age. Neanderthals mainly survived based on hunting megafauna like wooly mammoths. When those megafauna died out with the end of the ice age, so too did the Neanderthals. They specialized in the climatic conditions of the ice age, so once the ice age ended, they did too. They just weren’t as innovative as Homo sapiens, nor did they possess the processing and communication abilities that we had to communicate information with each other on how to deal with their new environments and climates. They could speak, but not nearly to the level of complexity as Homo sapiens.

It can be the case that modern-day humans outlasted other hominin species specifically because of their “jack-of-all-trades” approach to surviving large-scale climatic events. Apart from playing a solely genes- or natural selection-based game, we counted on culture and learning as an existence hack.

Effectively, Homo sapiens use culture as an evolutionary cheat code. As Tim Waring, an assistant professor who studies human culture and cooperation at the University of Maine, said in an article published by ScienceDaily, “[…] culturally organized groups appear to solve adaptive problems more readily than individuals, through the compounding value of social learning and cultural transmission in groups.”

References (click to expand)

- Climate Effects on Human Evolution. Smithsonian Institution

- Boyd, R., Richerson, P. J., & Henrich, J. (2010, December 1). Rapid cultural adaptation can facilitate the evolution of large-scale cooperation. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

- Culture drives human evolution more than genetics. Science Daily

- Waring, T. M., & Wood, Z. T. (2021, June 2). Long-term gene–culture coevolution and the human evolutionary transition. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. The Royal Society.

- Why did Neanderthals go extinct?. Smithsonian Institution