Table of Contents (click to expand)

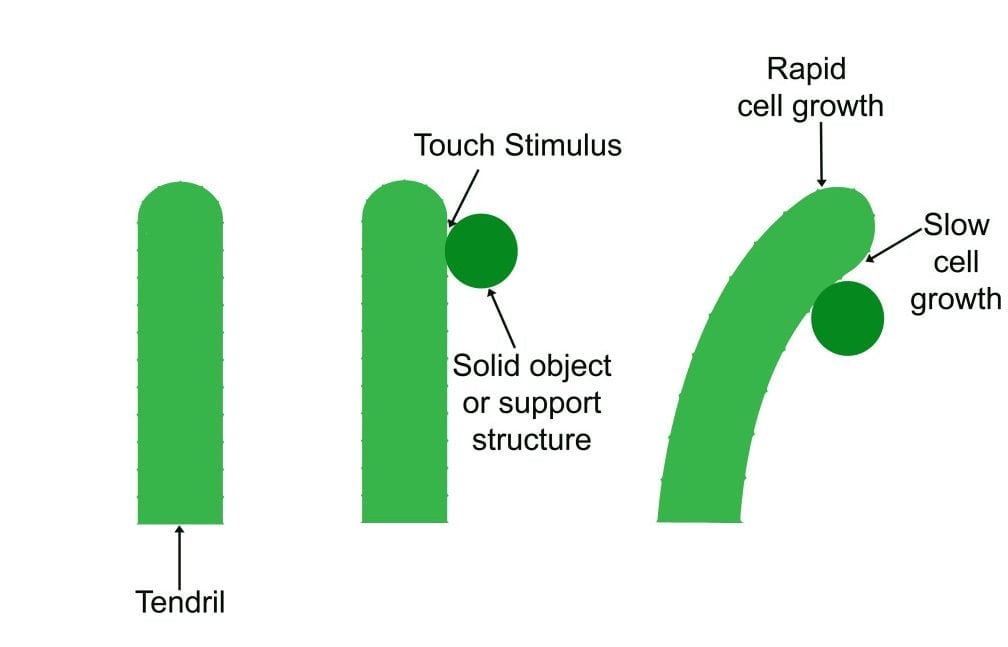

Tendrils are sensitive to touch. More formally, tendrils exhibit thigmotropism. They can change the direction of a plant’s growth in response to the touch of a solid object.

In the world of botany, climbing plants quite literally “stand out”. They are tenacious acrobats that cling and twirl around any form of physical support for survival and exploration. Not to be too philosophical, but the ability of vines to grow in the most unlikely places and rise up against all odds can be a lesson for us all. Be it the grill of your balcony, the walls of an abandoned building, or a huge tree in the heart of a jungle, they will hold onto just about anything to grow.

Don’t worry, you aren’t the first person to find climbing plants fascinating. It turns out that human evolution wasn’t the only thing that tickled Charles Darwin’s curiosity. He studied these remarkable climbing plants and ended up writing an entire book about them.

Climbing plants have a unique organ that makes them outrank other plants in terms of “habitat choice”. Quite simply, they are in possession of tendrils. Tendrils are slender yet robust threadlike strands that grow from the stem or leaves of a plant.

Vines or climbing plants depend on external support structures to grow. Thanks to tendrils that stretch outwards to search and cling, climbing plants are able to find support on which to survive. Now, how do they know if there is anything worth climbing on in the first place? It’s not like they have a periscope they can pop out to scan their surroundings for a pole or plant.

Recommended Video for you:

How Do Vines And Creepers Find Support?

The cute curly strands on the plant play a critical functional role. Tendrils are pretty useless if they can’t find anything to cling on, but tendrils help them find support to cling on.

Tendrils are sensitive to touch. More formally, tendrils exhibit thigmotropism. If you break down the word, thigmo means “touch” and tropism refers to “the act of growth or movement of a plant in response to external stimuli”. Basically, thigmotropism is the change in the direction of a plant’s growth in response to the touch of a solid object.

Thigmotropism comes in two types: positive and negative thigmotropism. Roots show negative thigmotropism. When the roots “feel” an object in the soil, they move away from it. This allows the roots to spread out towards empty pockets where there might be water.

Movement in tendrils works just the opposite as it does in roots. Tendrils of climbing plants show positive thigmotropism. When the tendril feels a solid object, it moves towards the touch stimuli. It then coils itself around the said object and continues to grow on it. Through differential growth, the plant curves towards the object and wraps itself onto the source of support. To learn more about thigmotropism, click here.

Do They Know What They’re Climbing On?

Plants lack the sophisticated neural networks of the mammalian brain, but they are still perceptive to their surroundings. This awareness informs them of which plants are okay to climb on and which they should avoid.

It is quite common for climbing plants to come across plants of their own species. In the race to survive, coiling around a plant of the same species seems counterproductive. Plants of the same species pose a threat, as they will act as strong competitors for space and resources, as compared to plants of different species.

Additionally, given the fact that the climber plants themselves lack a strong stem to support their growth, clinging onto a plant of the same species seems pointless. It’s like using a twig as a walking stick. Thus, in view of natural selection, staying clear of a plant from the same species sounds like a smart choice.

According to a study conducted at the University of Tokyo, climbers can differentiate between plants of their own species and other species. They found that the tendrils of C. japonica can taste oxalate. Oxalate is a chemical present in high quantities in the same plant. Upon tasting oxalate on the supporting structure, the plant recoils, moving away from that plant. On the other hand, the plant did not avoid coiling around sticks that were coated with chemicals like agarose or citric acid.

Scientists believe that the ability to sense chemicals may be widespread among this group of plants.

Conclusion

As it turns out, climbing plants are more sophisticated than we originally thought. They can not only change the direction of their growth based on the touch stimuli, but can also identify if the support they plan to climb on belongs to the same species or not. Some plants make their choice of a plant for their support based on the diameter of the trunk. For example, a plant like Wisteria sinensis will not climb on another plant that is more than 15 cm wide!

References (click to expand)

- Thigmotropism in Tendrils - Biology - Kenyon College.

- Gianoli, E. (2015, January 1). The behavioural ecology of climbing plants. Aob Plants. Oxford University Press (OUP).

- Fukano, Y. (2017, March). Vine tendrils use contact chemoreception to avoid conspecific leaves. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. The Royal Society.