Table of Contents (click to expand)

Birds use a few different methods to navigate while migrating. They may use visual cues like landmarks or the position of the sun and stars. They may also use magnetic fields to help them orient themselves. Some scientists believe that birds use a quantum mechanic ability to detect magnetic fields in order to navigate.

In many parts of the world, people can look up at certain times of the day and see huge flocks of migrating birds passing overhead. It has been noted by researchers and ornithologists throughout history that birds often take the same migratory paths year after year. Furthermore, many of them return to the exact same locations at either end of their migrations, spots sometimes separated by tens of thousands of miles!

On the other hand, some humans get lost walking out their front door, so what gives birds the edge? How do migrating birds find their way?

Recommended Video for you:

A Bit Of Birding Background

There are about 10,000 bird species in the world, and nearly 20% of them are long-distance migrants. These migratory species typically move in a north-south directional pattern between their “breeding” grounds and their “wintering” grounds. Migration primarily occurs due to the need to reproduce, the availability of food, and increased/decreased threats of predation.

The size of migratory routes can vary widely, from as little as a few hundred meters to well over 50,000 miles. These migratory patterns have been recognized by humans for more than 3,000 years, yet this ability in birds remains an incredibly mysterious skill. Certain conclusions and observations have been made to clue us into this special secret, but there are still a lot of questions….

How Do Birds Migrate?

Using Their Common “Sense”

Since migratory paths seem to remain the same year after year, scientists have long believed that birds likely follow the landscape to find their migratory destination. Visual markers, particular sounds, distinct smells, and learned social cues may play a significant part in this process, according to ornithologists. This type of honing ability is often called piloting. Imagine flying thousands of feet above the ground below you; you could see rivers, forests, mountains, and natural landmarks splayed out like a map.

It is believed that birds can create a mental map of their migratory pattern, and since large-scale environments don’t change that often over the course of a bird’s lifetime, this method of navigation can be highly effective. It is speculated that young birds may learn this mental map through social cues, namely joining its parents in their annual migration, like a test run, before they go out on their own.

Using everything from coastlines to superhighways, birds don’t need a map because they’re constantly watching the life-size map laying before them. Unfortunately, this doesn’t account for migrating at night, or in conditions where visual and other sensory cues aren’t as effective.

Looking Up, Rather Than Down

For birds in those less than ideal conditions, of when traveling over large bodies of water or tracts of land without discernible features, another method has been proposed. Some things that never change on a yearly basis are the orientation of the sun and stars, so it is believed that some bird species use celestial navigation, like sailors of old, to find their way through the more challenging legs of their journey.

Vision-Based Magnetoreception

One of the more complicated theories to explain avian migration involves bird species’ ability to detect the magnetic fields of the Earth, and subsequently follow those fields to their ultimate destination. This ability to use “invisible” waves was hard for some ornithologists to swallow, but it was proposed that some bird beaks contain magnetic particles that act as a compass. Recently, this theory has fallen out of fashion, replaced by the theory of vision-based magnetoreception.

The concept of vision-based magnetoreception means that birds can “see” magnetic fields and align themselves with the direction of the field they want to travel. If a bird is migrating south, it will align with a south-facing magnetic field and be on its way. Experiments in laboratories have actually generated artificial “magnetic south”, and birds moved in that direction.

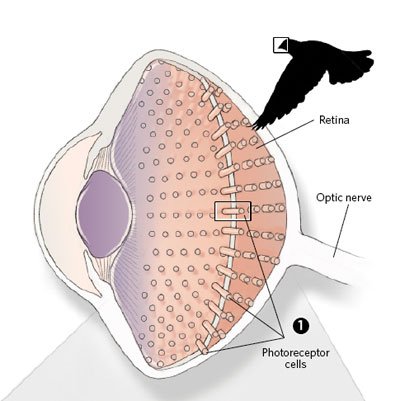

Presuming that this ability had something to do with sight, researchers determined (through a rather amusing goggle experiment) that birds require clear vision in their right eyes in order to detect magnetic fields. The prevailing theory is that a photochemical compass, of sorts, is responsible. Essentially, photoreceptors in birds eyes cause a chemical process in the retina, which produces another type of photochemical species that is reactive to magnetic field strength AND direction. What this could mean is that magnetic fields appear as different moving colors to a bird, allowing them to follow a memorized path, making it very difficult to get lost during their journeys to and fro.

A Quantum Explanation?

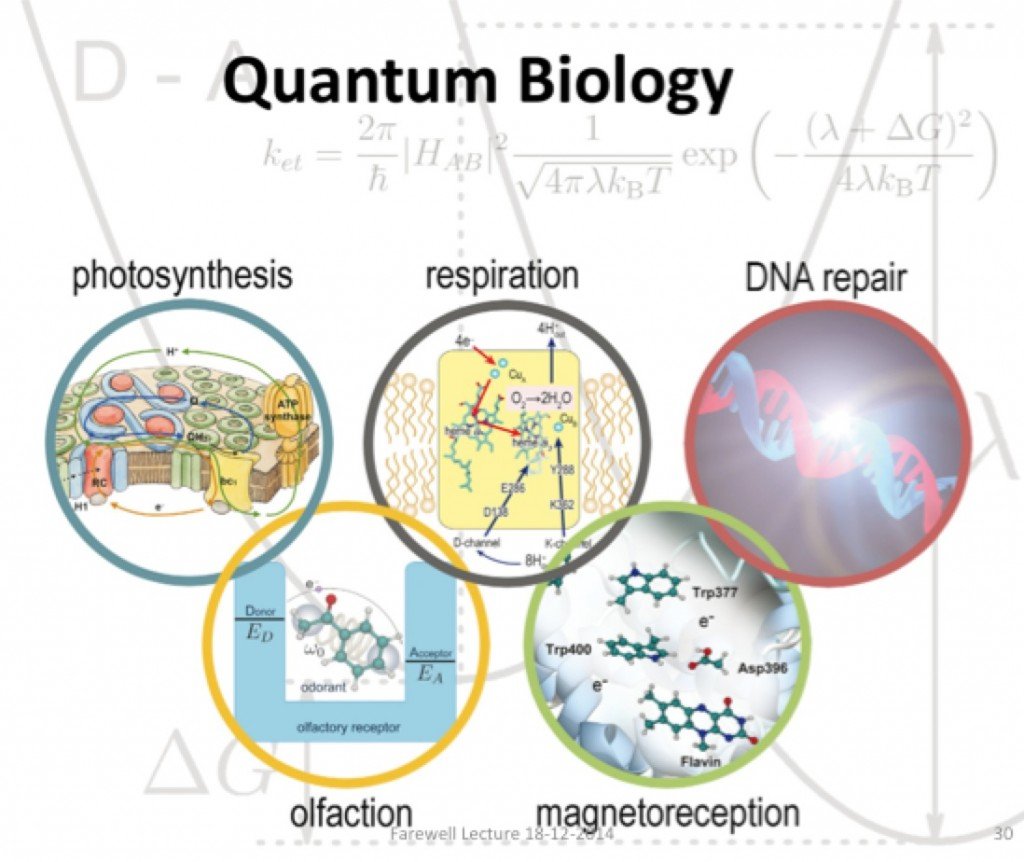

The last great mystery to vision-based magnetoreception is how this sort of magnetic field sensor can be present inside a bird’s retinal cells. One of the most recent theories suggest that quantum mechanics may provide the answer. For such a detector or strength AND direction, some mechanism would need to be in place to amplify the relatively weak magnetic effects of the Earth enough to be detected.

In quantum mechanics, a radical pair consists of two simultaneously created molecules, each with one electron of opposing, associated spin that makes these pairs highly sensitive to outside forces and magnetic fields. When a specific light-sensitive protein found in the retinal cells of birds, cryptochrome, is exposed to certain wavelengths of green or blue light, it can organically create these radical pairs. Magnetoreception like this is the latest field of quantum biology, and one that is currently being studied around the world.

There are still a number of theories out there, but this quantum explanation seems to make sense. Finding the right answer is crucial, however, because there are many man-made objects, such as radio towers and power lines, that generate weak magnetic fields. These unnatural obstacles have been known to disrupt migration patterns, which can be disastrous to bird populations. Understanding precisely how birds use these waves to navigate may help humans decrease their negative impact on bird migration.